The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

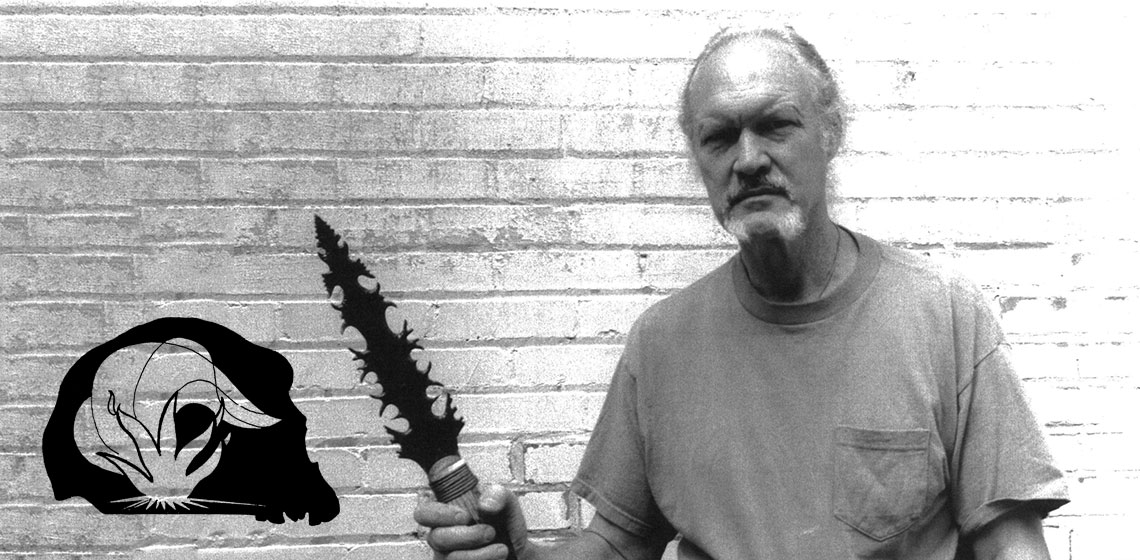

Interview: Dr Errett Callahan

This interview with Dr. Errett Callahan began in the fall of 2010 during an 8-hour car ride from his home, Cliffside, in Lynchburg, Virginia to Gastonia, North Carolina where we both attended the first annual Reconstructive and Experimental Archaeology Conference (REARC). It continued over several months via phone conversations and snail mail correspondence. I am honoured to have had the opportunity to interview my teacher, mentor, and close friend for this publication.

What individuals would you consider to be the most influential in your life/research/career? Who are you most thankful for having had contact with? [Dr. Callahan was originally asked these two questions separately, but after considering it for some time, realized that the answers were the same for both questions]

For sharing their philosophy, craftsmanship, and generosity, the names that first come to mind are Don Crabtree, Francois Bordes, Gene Titmus, J.B. Sollberger, the DeHaas’s, John Coles, Steve Watts, Thorbjørn Peterson, Kjel Knutsson, Jacques Pelegrin and, while not an individual, the Society of Primitive Technology. Numerous supporters and funders including Jean Auel, the C.R.A.F.T. INSTITUTE, Lejre, the King of Sweden, the Schiele Museum, Bob Verry, and my customers have made my research possible. I have also been impacted by, and am thankful for my followers including my many students, my customers, my family, patrons Ray Wood and Bob Richards, Hugo Nami, Bill Schindler, Greg Nunn, Hans-Ole Hansen, Jan Apel, Mike Frank, Peter Kelterborn, and Dan Stueber.

Who, in your mind, do you feel contributed the most to the field of experimental archaeology?

John Coles, Peter Reynolds, Hans-Ole Hansen, Steve Watts, Kjel Knutsson, Jack Cresson, David Wescott, the DeHaas’, and Hugo Nami. I must also acknowledge two organizations: the Schiele Museum and the Society of Primitive Technology (SPT) along with their publication, the Bulletin of Primitive Technology for their contributions.

Where do you see the future of Experimental Archaeology going and what do we need to do in order to ensure its success?

I believe the field must try to embrace all types of research and researchers. The SPT must do the same or else I fear it will splinter and fall apart. We should follow European models. We must do more to apply our knowledge to environmental understanding.

We will see the death of traditional knapping if the ‘dark side’ takes over, as it almost has. I am also leery of the fascination with digital technology and fear it may replace and kills the grassroots philosophy of hands-on learning and instruction.

We, experimental archaeologists and primitive technologists, need to be more service oriented. We possess the knowledge and know-how to prepare the world for the next disaster, such as Katrina and the wide disasters of 2011, but fail to spread the word to the general population.

We need to consistently apply our research findings back to archaeology. We cannot just stop with making and testing. If we fail to do this, we will be just another special interest group.

I would suggest that there be a registry of certain key experimental sites. Those should be identified, protected, and interpreted. Some sites may, though ignored now, prove to be as important in time as are excavated archaeological sites, and may indeed even be excavated themselves - - as with Overton Down and the Old Rag experimental station in Virginia. This latter site, after some 30 years of observation, resulted in a 800-plus page report. Naturally, some committee would have to be formed to decide what the criteria would be for ‘important.’ This would not be just any place where a test was done, but one in which a body of research knowledge emanated so as to be shared with others in the field and/or the general public. Such sites might be determined by state or nation or worldwide. To get the ball rolling I would suggest European sites such as Lejre, Butser Hill, the DeHaas’ Polder site, and similar centres where projects were carried out and reports resulted. In the United States I would suggest sites such as the Rabbitstick site, the Wintercount site, Dirkey’s Lake (Crabtree’s field school), Old Rag, Cliffside, Pamunkey, and the Schiele Museum’s aboriginal site. This is not the time for an in-depth explanation. I just wanted to introduce the idea here and let someone else run with it.

What are the most pressing issues facing the field of Experimental Archaeology?

What the field desperately is in need of is a repository for experimental tools made and/or used for experiments and testing or even just created for art’s sake by modern craft producers. I envision this as something like a museum that could serve as an educational facility, storage facility and a library. It should be traditional only, not inclusive of tools produced through high-tech knapping by machinery. Otherwise, as this generation passes, our ‘stuff’ will end up in yard sales. The library in this repository should include the personal libraries of noted pioneers in the field as well as correspondence. Don’t let our books on paper become extinct! It should also be a place where retired, tired, or deceased researchers may donate or will their leftover productions. Crafters deserve a better fate than having their works ending up in some big yard sale of sticks and stones. It should also include a sales shop where worthy crafters may have their replicas and reports sold not only among each other but also to the public at large. Sales could go toward funding on-going projects. There would also be a facility to put/store raw materials - materials such as flint, antlers, bones, and the like. These could be leftovers from finished projects, or simply a place where material donations could go - to be shared by all. Sales could possibly be not only a source of income, but also where those without funding could obtain material without cost or borrow for a time - up for grabs – no waste.

Let us each ask ourselves this: where will our precious possessions be in 100 years from now? What can we do now to prevent the history of our endeavours from being forgotten, destroyed, or burned (as, unfortunately, we are doing with too many of our house reconstructions). What are we doing to prepare the 2nd and 3rd generations, our children and grandchildren for how to appreciate, protect, and otherwise deal with these the products of we, their ancestors? Yes, we will become ancestors some day – at 74 years old I am getting pretty close now.

This problem has been overcome by many European researchers, but many in the US do not have a catalogue of their productions. I would suggest some kind of listing, and insignia, as the SPT endorses, so in the future their works may be identified – by maker, project, nations, etc.

The Bulletin of Primitive Technology is grasping at straws for articles. Spread the basic topics around more; both specialize and generalize. It needs to stick to what has worked, avoiding tangents.

Stop burning down perfectly good reconstructions just because you don’t know what to do with them. Instead, researchers should engage in deep time studies such as were accomplished with the Old Rag Project and Overton Down.

Researchers should spend more time on making experimental archaeology relevant to archaeology. We need to predict what should be expected and let the archaeologists explain that. I laid some groundwork for this during my research conducted at Lejre between 2004 and 2006, the reports of which exist at Lejre as well as in Volume III of my forthcoming dagger book. We may never be able to distinguish the difference in the debitage or on the flake scars on the bifaces, but there must be some difference, for every change in behaviour yields a slightly difference result. So get out there and make those predictions and let experimental archaeology stand in the service of Archaeology. If it’s not relevant is just playing with toys again.

What have you learned from your experiences as a practitioner of Experimental Archaeology?

First off, I have gained a great appreciation for the past, for other cultures and other times. I have also learned a lot about my own culture, self-reliance, and the problems of worldwide technologies.

It has been said that we are currently in the ‘Golden Age’ of flintknapping. In the 70’s, ‘replicas’ were not as ‘good’ as originals. Now they are ‘better,’ more controlled, more accurate, more precise – in other words they are true replicas and more reliable. In some cases, knappers testing their skill levels have gone beyond relevance to archaeology, creating works of art. This, in itself is not a drawback until one begins to approach the ‘dark side’ via the use of modern tools and technologies not used in the past.

I have also learned that I, and other knappers, am guilty of ‘hoarding’. As I ponder my stockpiles of obsidian and other lithic materials, while also pondering my few remaining days, I realize that I have acquired far more materials than I will ever knap. Yes, I needed it for my classes, but I should have stopped amassing it years ago. The same may be said of the knapper from Idaho, from Dallas, from Denmark. Presumably, these materials will be circulated in the future and not just discarded. Still, I would encourage future knappers to collect only what will be used for research and stop hoarding. And so we learn.

I learned ways to help others in medical need. For instance, I learned from Crabtree how to produce obsidian surgical scalpels suitable for surgery today.

I learned how to clarify archaeological assumptions, in the service of archaeology, by scientific experimental testing – such as correcting population estimates through my work with the Cahokia House Project.

I learned how to introduce stone knives into the cutlery world so as to be taken seriously by modern knife collectors and bow hunters.

I also learned that I am hopelessly out-dated and will never catch up. At the same time I have been able to maintain my standards with consistency and reliability in an ever-changing universe. And that has provided me and mine with a sense of trust.

What differences do you see between how Experimental Archaeology is practiced in the United States and in Europe?

I see very little experimental archaeology being practiced in the USA nowadays. It seems to be exclusively ‘primitive technology’ and ‘primitivism,’ if you will. In Europe I see what I consider to be serious testing being practiced extensively and on grand scales. Practitioners in Europe seem to have a pride in their country that we don’t have. And this is probably because historically that is where their roots are. We are usually limited to American Indian cultures. However, the European interest is often restricted to academia. There are less hobby workers and volunteers who work without pay. There also seems to be little interest in ‘dark side’ knapping, though the Internet seems to be eroding away the traditional modes, unfortunately.

There is a lot more quality housebuilding, but little in the way of projects. Also, they are seem too eager to burn down their houses there, though the Cahokia archaeologists are just as guilty.

In Europe there are a lot more experimental research centres than in the US. There is also an increased appreciation for all technologies, not just the Stone Age. They embrace the bronze and iron ages, etc. They dive into technologies the Indians never were associated with. They don’t hesitate studying and displaying bones in museums for the sake of political correctness.

In USA we seem to be hamstrung by tensions between Native populations, archaeologists, and political awareness. We also have many more recreational knappers – both responsible and irresponsible. There is a great deal more ‘dark side’ knapping. We have had little in the way of ‘projects’ since the 1970’s and from what I can tell little or no official support of experimental research.

Is there any message you would like to leave us with?

On a personal level, I have tried to encourage a traditional philosophy. I believe it is through traditions that cultures pass on their values from one generation to the next. I believe that is what we should do now. I have stressed this in flintknapping so as to have our knappers pick up the traditional tools and see where they will take us. As opposed to the frightening contemporary trend of knapping with unauthentic tools, materials, and machinery that have no relevance to archaeology, to traditional solutions, or to whatever problems arouse our curiosity. Otherwise, we are just playing with toys.

Looking back on my life’s work, I can see that there was too little stress upon trying to clarify archaeology. Yes, when I do so, I was rewarded with a warm sense of satisfaction, one that I don’t get when just seeking ‘self discovery.’ I have been giving too much emphasis upon ‘self reliance,’ important as that may be to many. My deepest interest lies in the searching out of research questions that explain archaeology, using clear thinking and an understanding of scientific investigation.

I have stressed the three levels of authenticity, Play Therapy, Primitive Technology, and Experimental Archaeology. Arguments abound on all sides. These levels are spelled out in my Cahokia book and they have been excerpted in the Bulletin of Primitive Technology from time to time. They seem to fit right in with John Coles’ three levels noted in an earlier EuroREA report. Correct or not, this is what I have tried to accomplish in this life.

Keywords

Country

- USA

Brief Biography

Errett Callahan was born on December 17, 1937 in Lynchburg, Virginia. He died May 29, 2019. As a boy he was fascinated with the outdoors. He was especially influenced by the Boy Scouts of America; by his father, an outdoorsman, Scouter, and two-time National Champion in crew; by his uncles on his mother’s side, Charlie and Keith Taylor, naturalists from Jamaica; by the writings of Ernest Thompson Seton, his father’s counsellor at camp; and especially by Tarzan, or at least the concept thereof.1

His formal education includes an undergraduate degree from Hampden-Sydney College in 1960, a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1973 from Virginia Commonwealth University, a Masters degree in anthropology from Catholic University in 1977, and a Ph.D. in anthropology from the same in 1981. Then, in 1992, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Archaeology from Uppsala University in Sweden. In addition to studying at these institutions, he also taught classes based on experimental archaeology and primitive technology/flintknapping at both Catholic University and Virginia Commonwealth University from 1971-1980.

Dr. Errett Callahan has been extremely influential in the field of experimental archaeology in the United States and abroad since the 1970’s. As a reconstructive archaeologist2 , he developed and ran projects such as Old Rag, 5 phases of the Pamunkey project, St. Mary’s longhouse, Thunderbird House Reconstruction, Cahokia House Project, and dozens of smaller projects. As an experimental archaeologist, he conducted numerous ‘tests’ and ‘experiments’ within these projects. He was instrumental in the creation of the Society of Primitive Technology. Dr. Callahan was, in fact, the Founder of the organization and served as the president from 1988 to 1996. He has continued to serve as an advisor to the society since his retirement from the board.

Callahan has been flintknapping since 1956 and began taking his work seriously by recording his production since the early 1960s. As of 2010, he had produced 9884 meticulously recorded knapped tools, including well over 1,000 hafted cutlery knives. He also pushed his skill and know-how beyond replication work and began to produce creations of ‘Fantasy Cutlery.’ He was a member of the American Bladesmith Society (ABS) and a past voting member of the Knifemaker’s Guild, where he was the first to ever have stone knives admitted.3 He sees this as a turning point resulting in his moving knapping away from just imitating ‘Indian relics’.

Following Don Crabtree’s lead, Callahan has been producing obsidian surgical scalpels for the medical trade for years and has had a number of surgeries performed upon himself and his family as a demonstration of his faith in the product. More recently, he has been working for the past 30 years on his Danish Dagger research that includes the reproduction of 250 daggers, 88 of which are undergoing intensive analysis.4

No doubt his research over the past 40+ years has influenced the fields of experimental archaeology and archaeology as well as helping all of us gain a more accurate appreciation for the past. However, many, including Callahan himself, would consider teaching his most important contribution. He currently considers himself retired, but has taught flintknapping and other primitive technologies to over 1000 students since 1971. Perhaps more importantly, he has lived his life, conducted his research, and taught according to a traditional philosophy or ‘code’ of ethics. With regards to flintknapping, this code requires the use of traditional tools and techniques, opposition to what he considers the ‘dark side’ knapping of fraudulent replicas passed off as ‘Indian relics’ made with modern machinery, and defence of knapping ‘ethics’ which includes signing of all knapped tools. He believes that all of his achievements have now been surpassed by his students, and, as a true teacher, this pleases him.

He has also been the builder of bridges. One of his main goals in the 1990’s was to bridge the gap between the New and Old World experimental archaeology traditions. His work with researchers on both sides of the Atlantic as well as his Danish Dagger research conducted for many years at Lejre helped accomplish this objective. He also attempted to create a bridge between what he considers the commercial ‘dark-siders’ with academic archaeology, but failed to make that connection. His company, Piltdown Productions, filled the need for traditional supplies for flintknappers and his annual reunion continuously establishes and re-establishes contacts between former students and friends.

Anyone who has ever met Errett realizes his attention to detail in every aspect of his life and research. This translates into copious note taking and data recording. His home, Cliffside, is filled with a plethora of notes, data, replicas, debitage, etc. He keeps EVERYTHING in the hopes that someday it will be useful to the right person conducting the right type of research. For instance he has data from a 10-year period recording the number of parallel flake removals generated while making the knives in his catalogues as well as the length of cutting edge all of these ‘tools’ created. Often archaeologists can get lost in data recording, but Dr. Callahan has pushed beyond that. It is not the meticulous data recording that comprises his most important contributions, but rather the passing on to others the essences of what it all boils down to and how the data help decode and make sense of the archaeological record. He continuously stresses how the knowledge and know-how he passes on to his students and this data helps us understand all of prehistory across time and space was well as providing the context within which to view our own culture and ourselves.

- 1Errett recalls that he never saw a Tarzan running around the jungle with a backpack on. He carried his need and solutions in his head. He was not only totally self-sufficient but he had this most wonderful tree house with running water, and elephant elevator, and stone axes (to crack ostrich eggs); and he wanted to do likewise. Well, this wasn’t Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan as he later found out. It was Johnny Weissmuller’s and MGM’s. But all those Tarzans filled him with a burning desire to make his own tools and primitive houses. So the Tarzan concept must be considered a serious influence on him. This resulted in a year’s stay in East Africa in the 1960’s doing landscape paintings and looking, in vain, for a jungle like Tarzan’s. But he did build a modest tree house, cooked some plantains there, and slept in it as monkeys chatted all around and leopards prowled below.

- 2Callahan defines his use of the terms reconstructive archaeologist and experimental archaeologist in his pending Cahokia report.

- 3Callahan’s website www.errettcallahan.com depicts some of his creations

- 4This study is aimed for a three volumes series entitled NEOLITHIC DANISH DAGGERS: AN EXPERIMENTAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY, co-authored with Jan Apel. Volume 1, THE FLINT DAGGERS OF DENMARK, has already been published.