The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

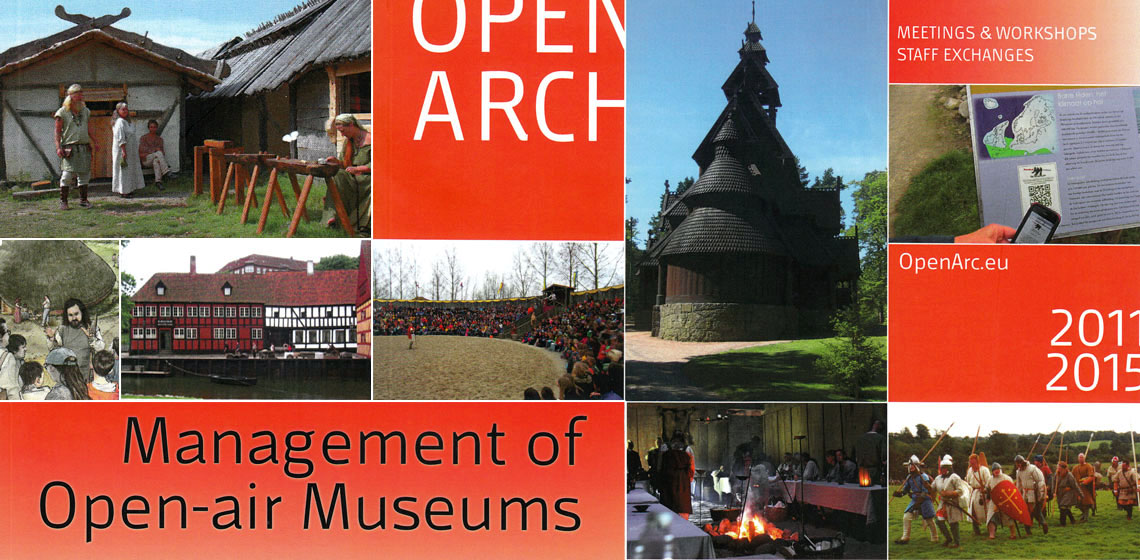

Book Review: Management of Open-Air Museums. Workpackage 2: “Improvement of Museum Management” by Jakobsen, B & Burrow, S (eds).

The five year OpenArch project concluded in 2015. It was an effort to create a permanent partnership between Archaeological Open-Air Museums (or, AOAMs) in Europe. The project saw eleven participating organisations come together to – among other objectives – produce work packages that would be accessible to people with an interest in the workings of AOAMs.

Jakobsen and Burrow edited this second package which was published with the help of the Cultural Program of the European Union. The resulting book is a fast-paced and slim volume. Within a space of one hundred and thirty pages the editors manage to cover a significant number of topics about AOAMs. The work package is divided into seventeen overarching sections. No book about Archaeological Open-Air Museums would be complete without discussing their history, and so this handbook begins with that obligatory story of Artur Hazelius and Skansen. From this origin story the book proceeds onto issues which a person interested in the operations of AOAMs would find useful.

With data gathered from the OpenArch participants, the work package is able to offer the reader figures and averages about visitor figures (number of total visitors made up of school tours, for instance), as well as the makeup of part time versus full time employees. Even issues of long-term health are brought up with the help of the information provided by participating AOAMs. While it is not novel to recover these kinds of figures for research purposes, their inclusion in the handbook offers it in a smooth and rapid way without lingering to commit to lengthy analysis which researchers in more academic works have tended towards. This is perhaps both a good thing – keeping with the matter of fact brevity of the book – and less so: leaving the reader without potentially useful information on how each of these figures impact AOAMs. Of course, brevity seems the point.

A selection of larger, academic texts about AOAMs exist. While their subjects are also on the same kinds of sites that are used in this book, their focuses have differed from that of Jakobsen and Burrow’s. Many of these have taken the form of ethnographies about representation (such as Snow 1993 and Peers 2007) or as a work aimed at historiography (Magelssen 2007). The topic of AOAMs is approached in the theoretical, academic world. Of course there is nothing wrong with this, actually examining the performances and issues of representation is instrumental to the production of better strategies for engagement. However, this work approaches the AOAM from a practical stance. It is meant to serve as a guide to assist management rather than as a purely mental exercise. This piece of work has to fit many topics together, while other works have a luxury of space to use for a more focused picture.

Visually speaking, the handbook is charming and has been filled with a substantial number of images. The editors’ selection of these is certainly not superfluous, and the pictures offer a useful supplement to the work. In fact, they seem to take up more space than the words in many places. There is nothing wrong with this approach. It only makes sense to offer visual media when covering the subjects which this work does. The book does not force dense text on anyone, rather, it lets the pictures do the heavy lifting. This use of images could be incredibly helpful to someone who is in the process of dealing with modern practicalities and realities, while still needing to tend to the aesthetic of their buildings. For instance, matters of health and safety are a cause for concern to AOAMs; buildings which can contain fires require fire extinguishers and other modern facilities, such as fire escapes and lighting, could also greatly detract from the image which the museum is trying to evoke. Jakobsen and Burrow tackle issues like this with the assistance of images which show methods of concealing these modern objects from the immediate sight of visitors.

About half of the book is devoted to several case studies which took place at one of OpenArch’s partners, St Fagans National History Museum. These work with issues raised in the first half of the handbook and highlight ways towards resolutions. While it is normal to consider the research that AOAMs undertake as being something to add to the notion of ‘authenticity’, these cases show otherwise. Some experiments include using 3D models and sophisticated lighting labs in order to produce reconstructions that more efficiently use the sun to maximize interior lighting, or analysing the temperature retention of buildings to come up with strategies to reduce the negative impact that overly cold structures can have on costumed interpreters. It is, in total, an incredibly interesting way of highlighting research methods that can be taken to improve the function of an AOAM. Thinking of experiments in this fashion also adds to the knowledge base that can be drawn from to create a better experience for everyone involved. It is a stimulating portion of the book with a lot of potential. However, the biggest drawback to this is that there are simply too few case studies. It leaves the reader wishing for more.

And in here lies the major issues with the book. Along with this comes issues regarding pacing and occasional inconsistent transitions. At times, thoughts are disjointed and an abrupt subject change is made. This is not an unforgivable problem. Jakobsen and Burrow do a very commendable job at drawing so many factors about managing AOAMs together in a simple, accessible way. This simplicity works most of the time, but it is easy to see how a reader could be left wishing that there had been more detail in each section. That would have required either a much larger book, or one which greatly limited its scope. Both of those solutions would come with their set of problems: either failing to be a quick handbook, or letting certain issues fall through the cracks. Neither of these are optimal – though a thicker handbook, along the lines of a Management of Open-Air Museums for Dummies could have potential.

Until that day, the Workpackage: Improvement of Museum Management is available mainly as a pdf (only 200 physical copies were printed). Overall, it is a thought-provoking read. Jakobsen and Burrow lean towards brevity, and make heavy use of visuals to illustrate potential options for practical-minded readers interested in the management and maintenance of AOAMs. This book makes for an excellent supplement for those of us in the museum sector who want to know more about what is involved in running these unique and interesting kinds of destinations.

Book information:

JAKOBSEN, B, BURROW, S. (eds), 2015, Management of Open-Air Museums. Workpackage 2: “Improvement of Museum Management”, Hollviken: Fotevikens Museum

Keywords

Country

- Sweden

- United Kingdom

Bibliography

MAGELSSEN, S (2007) Living History Museums, Undoing History Through Performance. Toronto: Scarecrow Press.

PEERS, L (2007) Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories and Historic Reconstructions. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

SNOW, SE (1993) Performing the Pilgrims: A Study of Ethnohistorical Role-Playing at Plimoth Plantation. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.