The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

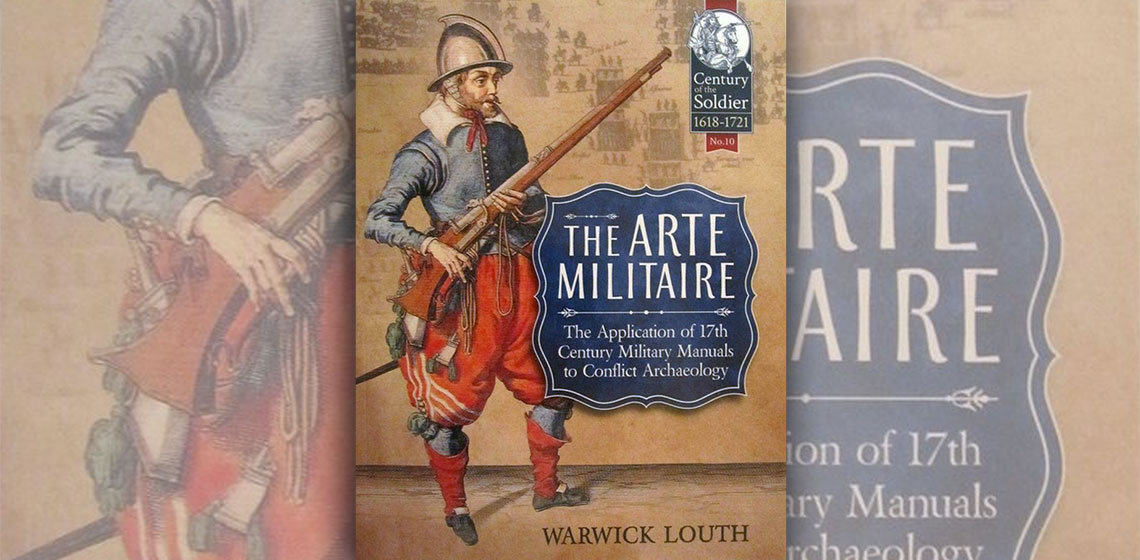

Book Review: The Arte Militaire. The Application of 17th Century Military Manuals to Conflict Archaeology by Warwick Louth

The book consists of the rewritten essay of a master thesis. The author got his master's degree as a battlefield and conflict archaeologist from the Centre of Battlefield Archaeology at University of Glasgow founded by Professor Dr. Tony Pollard in 2006.

I myself have studied at the Centre of Battlefield Archaeology back in 2007, and it was a pleasure to dive back into my old field. It was especially a pleasure as this book is very well written and well researched.

The book covers the use of military manuals to sites of conflict and how they can be applied in the research and analysis of such sites. The manuals have long been recognised for their images and as source material for equipment, but they have never been put to the test as sources for interpreting battlefields. They have for a while been used in the re-enactment world and the HEMA Alliance (Historical European Martial Arts) as a way of understanding historical martial arts. It is a pleasure to see this approach being recognised and used in the academic world as well.

This book reveals a whole new source of materials for battlefield and conflict archaeologists, and even though it mostly is concerned with the field of battlefield and conflict archaeology, it is also touching upon the field of experimental archaeology; as such it deserves a few words of recognition.

Recently the use of different fighting manuals and military manuals has been tested in varying degrees in the re-enactment and experimental archaeological world. Some have just been used to test different fighting techniques within the local re-enactment group, others have been subject to master theses at university level. E.g. Rolf Warming's master thesis on “Shields and Martial Practices in the Viking Age”; Warming is also the founder of “Society for Combat Archaeology” which aims to put historical combat myths and objects to the test, and experiments to gain a better knowledge of past conflict. "The Arte Militaire" falls into the latter category and is a star example of how re-enactment, experimental archaeology and classical genres of archaeology can go hand in hand and bring us new knowledge, results and methods to gain the best possible view of the past.

The manuals have, as stated, been used in experimental archaeology and amongst re-enacters for a while, but to fully include them as valid source material in archaeology has been missing in the broader picture. No more.

The analysis of the manuals, combined with the application of the method to different battlefields, shows the strength of the manuals. They also show that the different drills can be detected on battlefields, thereby telling us how the forces moved, what tactics they employed and which theoretical models the different officers and armies used.

It gives a whole new level, a more individual and personal one, to the subject of conflict archaeology, as it is now possible to detect how units moved across the battlefield. This was of course first recognised by Douglas D. Scott in the mid-1980’s with his work on the battle of Little Big Horn, where he proved that the military movement was different than anticipated from popular stories. He showed that archaeology can prove historical records wrong and he brought forward new information about the battle.

This was a huge step for conflict archaeology and it was the kick-off for the whole field, which has since developed into the acknowledged field it is today. In much the same way, Louth now shows in his essay how military manuals can bring forth new information about drill movement, and explain battle outcome.

The author also includes re-enactment and experimental archaeology as source material when studying battlefield and conflict archaeology. As this particular area of archaeology is quite difficult with none or few physical traces left and only scattered material on battlefields that have often been subject to development or agriculture, it is important to use all methods available to get the best results as possible. Re-enactment has developed fast over the past twenty years, and many groups are very good and have got their source materials down. Many members of re-enactment groups also have some kind of degree in history or archaeology, and as such the groups are very well founded within the academic tradition, and their research is thorough. The re-enactment scene makes it possible to test theses about drill movements in the proper gear, with the proper equipment and with people who are somewhat used to handling a weapon of the type in question. This makes the results more correct and eliminates biases and faults.

This use of experimental archaeology within a re-enactment setting is something I believe we will see a lot more of in the future. It will of course always be modern persons in modern gear made after historical sources and archaeological finds, but it will minimise the area of faults and give a more correct picture and thereby a better result.

Using experimental archaeology and re-enactment as a method shows the potential to recreate and understand the effectiveness, use and limitations on a battlefield and within the group.

Within the book, the author only touches upon the subject of experimental archaeology as a method, but it is clear that applying manuals of any kind to conflict archaeology will give some understanding of how the equipment works, how a group moves, how they reacted to commands, etc. As long as one is aware of the fact that the manuals represent the ideal, and not necessarily that which actually took place on the battlefield.

By applying the use of experimental archaeology as well as re-enactment to sites of conflict the picture broadens, as re-enactors are just as likely as their historical counterparts to drop or lose items, trip, fall, etc., thus forming a new context of archaeological potential. Studying how re-enactors move and work in formation makes it possible to investigate and interpret the archaeological record. It enables us to analyse personal objects found at the site and put them into some sort of context.

For a long time, re-enactment has been looked down upon by academics, and it still is sometimes, but I truly believe that in applying all possible aspects, we have the best chance of getting the best results.

It is liberating to read this book and see both experimental archaeology and re-enactment applied together with classical archaeological traditions. The book shows how far we as a field can go if we work together and use the methods available.

Book information:

LOUTH W. (2016). The Arte Militaire. The Application of 17th Century Military Manuals to Conflict Archaeology. In Century of the Soldier 1618-1721, ISBN 978-1911096221. £19.95. http://www.casematepublishing.co.uk

Keywords

Country

- United Kingdom