The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

Book Review: Viking Age Brew, by Mika Laitinen

What did ale and beer taste like in the past? How was it made? What sort of equipment did they use and what were the ingredients? The answers to all of these questions, and more, can be found in this book. Archaeologists, experimental archaeologists, brewing historians and anyone interested in ancient technologies will find this book invaluable as an easily accessible study and explanation of pre-industrial beer brewing techniques.

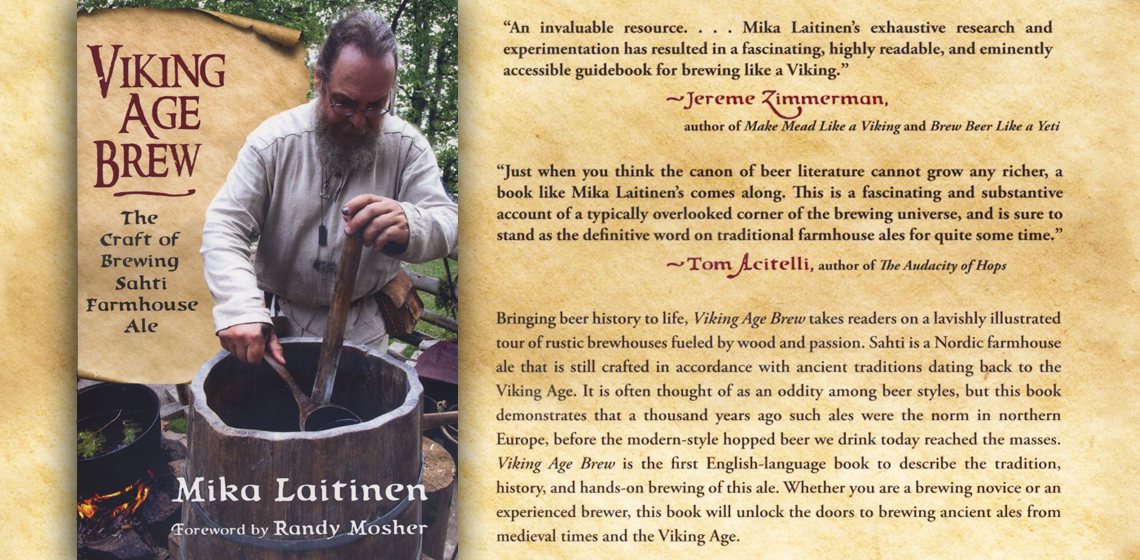

The author is an acknowledged expert in traditional beer brewing techniques and, being a skilled brewer himself, he understands the brewing process from a practical and technical perspective. It's possible that some EXARC members have seen Mika doing brewing demonstrations at medieval markets. He was at Turku in 2016 where he worked with Kalle Markkula and Jouko Ylijoki of the Olu Bryki Raum Brewery, Isojoki, Finland. Just to be clear, Kalle is the brewer on the cover of this book.

If you have not yet seen their 'mashing in' demonstrations at medieval markets they are definitely worth looking out for. The 'mashing in' is the stage of the brewing process where crushed malted grain is mixed with hot water to make the sweet wort. It smells delicious. It tastes sweet. It is liquid malt sugars. When yeast is added to the wort it converts the malt sugars into alcohol by the process of fermentation.

Of course, not everyone can go and see a medieval brewing demonstration. This lavishly illustrated book, written for brewers and non brewers, is the next best thing. Mika presents a well-researched ethnographic study of the living tradition of making malt, ale and beer from the grain using traditional equipment and techniques. His book illuminates these ancient crafts on a small, domestic scale. It celebrates the living tradition of farmhouse brewing which has, against all odds, survived in some areas of Finland, Norway, Sweden, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia and Russia.

The ephemeral aspects of brewing that do not survive in the archaeological record are well illustrated. There are numerous photographs of brewers using wooden vessels for mashing in, lautering and fermentation. This is exactly the same equipment that was used by brewers in northern Europe during Iron Age, Viking and Medieval times. The brewing process has not changed.

There are also detailed descriptions of brewing techniques, for example, brewing in a wooden mash tun with hot stones. The skills, specialised knowledge and experience of the brewers is clearly explained. These techniques and traditions have been handed down from one generation of brewers to the next.

There is a lot of technical jargon in the world of the maltster and the brewer. The book begins with a general introduction to the subject, and then a clear explanation of established basic brewing terminology. What is malt and how is it made? What is involved in the mashing and fermentation processes? Mika has interviewed and worked with many other farmhouse brewers. In Chapter Two he describes a typical brew day with Hannu Sirén, a master sahti brewer, as he prepares the juniper infusion, mashes in, and then lauters in a wooden trough, known as a kuurna in Finland. Presented as a photo essay, it demonstrates the fundamentals of the brewing process and sets the scene for the rest of the book and for an in-depth explanation of the brewing process in Chapter Eleven.

Some of the brewers that Mika has interviewed and worked with use modern equipment. They mash in metal mash tuns and collect the wort in milk churns. Fermentation takes place in plastic containers. The brewing process itself remains unchanged, with the same basic ingredients: malt, water, juniper branches and yeast.

There is a chapter on the history and prehistory of ale and beer brewing. This is a huge subject and it is not possible to cover every aspect. In northern Europe, sahti brewers use branches from the local Juniper communis to make an infusion with hot water for disinfecting the brewing equipment. The juniper branches are also used as filters and this gives the beer a unique flavour. Sahti beers have a strong malt character. Some brewers prefer to use rye malt, while others will use barley malt. This not only affects the flavour of the ale, but also the colour. Rye ales are much darker.

In other parts of Europe, before the introduction of hops, brewers have traditionally used herbs to flavour and preserve the ale. These ales can be made with herbs such as yarrow, bog myrtle, wild rosemary or ground ivy. Chapters Ten and Thirteen look in detail at the use of brewing herbs and there are recipes for recreating them. The flavours of these ales made with herbs are quite different to sahti.

The traditional brewing techniques described in this book are for making what is known as raw ale. This means making an ale or a beer without boiling the wort and without adding hops. No large coppers or cauldrons are needed. Wooden mash tuns and lautering equipment are sufficient. These, of course, cannot be placed over a fire, so hot stones are used to heat the water and the mash. Sometimes the only evidence that mashing in and brewing have taken place at an archaeological excavation of a Viking or Medieval site are the fire cracked stones.

One of the more unusual brewing techniques described in the book is keptinis, as it is known in Lithuania, or taari, as it is called in Finnish. This is an oven mash, involving mashing in the usual way, then baking the mash in an oven. This caramelises the mash and the resulting beer or ale has a distinctive flavour. Could this oven mashing technique be similar to the way that Ancient Egyptians brewed their beer, with beer bread? You will have to read the book for yourself and make up your own mind.

Kveik is a strain of farmhouse yeast that has survived in areas of Norway, Lithuania, Latvia and Russia. Mika describes them as heirloom treasures that have been passed down through the generations. The fascinating story of these farmhouse yeasts, known as Kveik and brought to the world's attention by Lars Marius Garshol, is told by Claire Bullen on the Good Beer Hunting blog. Her article “A fire being kindled – the revolutionary story of Kveik, Norway's extraordinary farmhouse yeast” tells the story. It is impossible to know how old these yeast strains might be. Some modern breweries have already started using them in commercial beers and home brewers are also using them.

Archaeologists understand that there is minimal evidence for making the malt and brewing the beer. These are mysterious processes to most people. This book provides an important missing piece of the puzzle, specifically, the ethnographic evidence that completes the picture of how malt and ale were made in the past. It is a very useful tool for anyone wanting to recreate an authentic ancient ale.

Book information:

Viking Age Brew, Mika Laitinen, Chicago Review Press, 2019

ISBN 13: 9781641600477, 240 page

Country

- Finland

Glossary of Definitions and Explanations

Malting and Brewing Words from Viking Age Brew

These are universal definitions to all brewers, the technical jargon of the craft.

Ale and beer are alcoholic drinks made from malted grain. The grain can be barley, wheat, rye or oats. Strictly speaking, ale is flavoured and preserved with herbs and beer is flavoured and preserved with hops. Today few people make the distinction between the two.

Malt is grain that has begun to germinate and has then been dried, either spread out in the sun or with warm air in a grain drying kiln. Germination biochemistry has only recently been scientifically understood, but maltsters have known how to make good malt for thousands of years. Grain requires both water and oxygen to germinate. We now know that enzymes are activated during germination. These enzymes convert the grain starch into sugars, the food source for the growing plant. The maltster interrupts this process by letting the grain begin to germinate, then stopping the process by careful drying in the kiln.

Traditionally, the harvested grain was put into a porous bag and left in a shallow stream for a few days. After this, the wet grain was spread out in a dark place to grow a little bit more. The maltster stops growth when the root and shoot begin to show. This is done by carefully drying the malt in a kiln.

Mashing or 'mashing in' is the process of mixing crushed malted grain with hot water to make malt sugars. The enzymes within the partially germinated grain reactivate and convert the remaining starches into malt sugars. The technical term for mashing is saccharification.

Mash tun: this is the vessel in which the crushed malt and hot water are mixed together to make the mash. There are several ways of achieving this. Hot stones are used to heat the mash in a wooden mash tun. Since the Iron Age, metal cauldrons have been used to heat the water for the mash tun.

Lautering is the part of the brewing process where the sweet liquid, the wort, is obtained from the mash tun. The brewer runs hot water through the mash and this washes the malt sugars out. The wort is collected in another vessel into which the yeast will be added.

Lauter tun: the vessel used for lautering. It can be a wooden tub or a hollowed out log, known in Finnish as a kuurna. A filter of straw or juniper branches is used to hold the grains, while the wort flows out through an opening in the vessel below the filter.

Sahti is the name for traditional farmhouse ale made in Finland. It can be made from barley malt or rye malt, or from a mixture of these. Brewers today often use a commercial sahti malt mix. Sahti is a malty ale with a juniper flavour that comes from the filter of juniper branches. Some sahti brewers use juniper infused water, which gives an even stronger flavour.

Kuurna: a trough-like lauter tun, traditionally made from a hollowed-out log.

Raw ale is ale made without boiling the wort. The wort is left to cool to the correct temperature for the yeast to be added to start fermentation.

Keptinis (the Lithuanian word) or taari (the Finnish word) is a rare and unusual style of ale or beer, made by mashing in the usual way and then baking the mash in an oven.

Wort is the sweet liquid malt sugars that are washed out of the mash by lautering. The wort is collected in another vessel.