The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

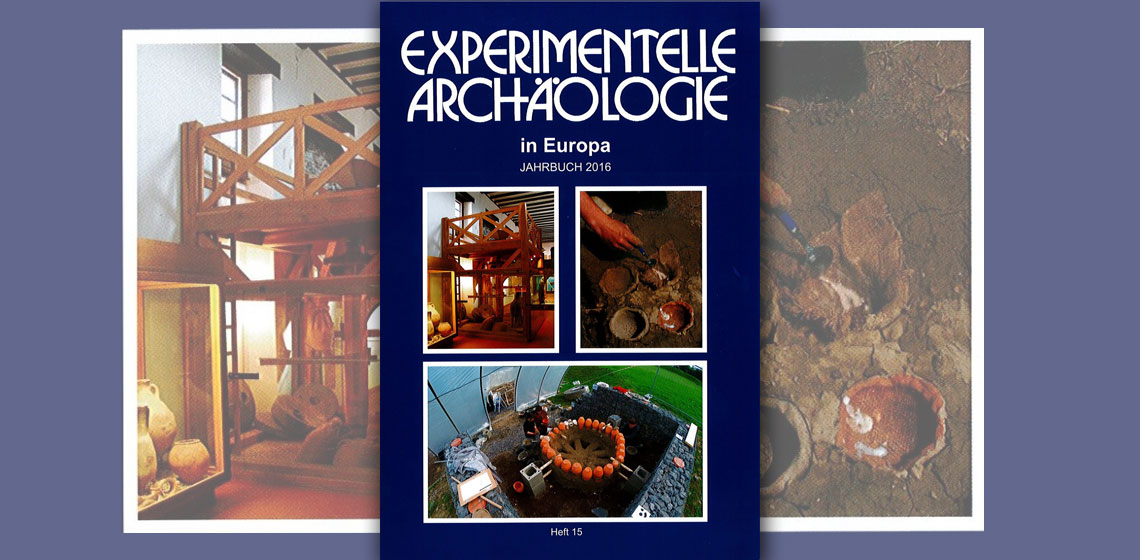

Book Review: Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2016

The periodical "Experimentelle Archäologie" is issued by Gunter Schöbel and the "Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der experimentellen Archäologie", together with Pfahlbaumuseum Unteruhldingen from Germany.

Issue no. 15 includes 223 pages of text, with numerous colour photographs. The content of the issue is divided into three main parts: Experiment und Versuch (Experiment and Attempt), Rekonstruierende Archäologie (Reconstruction Archaeology) and Vermittlung und Theorie (Interaction and Theory).

The first part (Experiment and Attempt, pages 12 - 96) consists of seven articles, addressing different, yet all very interesting topics regarding experimental archaeology. They deal with consumption of meat during animal sacrifices in Archaic Greece ("Fleischgenuss (???) beim Tieropfer in der griechischen Archaik" by Hannes Lehar); Early Iron Age salt production using textiles ("Masse und Klasse. Früheisenzeitliche Salzherstellung unter Verwendung von textilien am Fundort Erdeborn - Überlegungen zu Produktion und Handel" by Sebastian Ipach); Roman glass production ("Rohglas, Mosaikglas, Rippenschalen und römisches Fensterglas - ausgewählte Resultate der "Borg Furnace project 2015" im Archäologiepark Römische Villa Borg" by Frank Wiesenberg); lime kiln construction ("Kalkbrennofenbau in Klein Köris: Studiernede erobern die germanische Siedlung" by Christiane Ochs); reconstruction and experimental usage of a 5/6th century pottery kiln ("Experimental Reconstruction and Firing of a 5/6th Century Updraft kiln from Mayen, Germany" by a group of authors (Hannig, Döhner, Grunwald et al.)); experiments about fastening Merovingian cloaks ("Ein Rekonstruktionsvorschlag zum textilen Verschluss merowingerzeitlicher Viereckmäntel" by Tobias Schubert); and finally a paper about removing and washing stains in the 16th century ("Waschen und Fleckenentfernung von Textilien um 1500" by Fabian Brenker).

The latter paper considers in detail linen and woolen textiles that are exposed to different kinds of spoiling, such as grease, oil, tallow, pitch, red wine and ink, but also to simple wear and tear. During the late 15th and early 16th century, bed sheets and underwear were regularly cleaned with ash lye, since it leads to the removal of bad smells and makes the textile somewhat lighter. Other more persistent stains, were more or less successfully removed with hot clay (grease), boiled peas (oil), egg yolk or soap made of olive oil (pitch), milk or bitter orange juice (red wine) and white wine (used for removing ink stains). These simple experiments indicate that in order to keep one's clothes clean, many substances had to be kept at hand. Their efficiency does not come far behind modern washing powders, they only require more hand-washing and rubbing.

The second part (Reconstruction Archaeology, pages 97 - 136) includes three papers: the first one is about building a reconstruction of an early Neolithic well ("Neue experimentalarchäologische Studien zum bandkeramischen Brunnenbau im MAMUZ - im niederösterreichischen Museum für Urgeschichte in Asparn an der Zaya" by Wolfgang Lobisser), the second one discusses the manufacturing process of Iron Age crampons model ("Die Funktion bestimmt die Form. Die eisenzeitlichen "Steigeisen" von Niederrasen, Gemeinde Rasen-Antholz/Südtirol - ein Funktionsmodell" by Claus-Stephan Holdermann and Frank Trommer), and the last paper is about the reconstruction of two gold brocade baldrics kept at the German National Museum in Nuremberg ("Zwei goldbroschierte Wehrgehänge im Germanischen Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg, im Fokus der Experimentellen Archäologie" by Claudia Merthen).

The paper on Iron Age crampons would awake interest in every modern mountaineer and beyond. The shape and size of such crampons remained unchanged from as early as the Bronze Age. When fastened to shoes, they were used for high Alpine climbing, moving on icy or snow surfaces, and glaciers. The presented model is a replica of a pair of crampons discovered in grave 44 of the Niederrasen Iron Age cemetery in South Tyrol. The authors describe the process of making such crampons, indicating material, techniques and time spent for the entire process.

Within the third part (Interaction and Theory, pages 137 - 216) there are again seven different articles, most of them describing interaction in various AOAMs (Archaeological Open-air Museums). These include a paper about experimental archaeology in the Roman fort at Saalburg (Römerkastell Saalburg - 120 Jahre Experimentelle Archäologie by Rüdiger Schwarz); a tour through the AOAM Oerlinghausen (Vergangenheit anders sehen - Ein Rundgang im Archäologiscehn Freilichtmuseum Oerlinghausen mit Objekten by Sylvia Crumbach); two papers dealing with weaving in AOAM Xanten (Auf Tuchfühlung - ein Zweibaumwebstuhl im Einsatz vor Publikum im APX, Teil 1: Vorbereitung des Projektes by Gisela Michel und Teil 2: Durchführung by Barbara Köstner); a paper on how to make glass beads (Alles falsch? Vom Sinn und Unsinn von Perlenmach-Vorführung mit modernem Gasbrenner by Maren Siegmann); a paper about authenticity in living history (Aufreger Authentizität - Antrieb der Performativen Geschichtsdarstellung by Andreas Sturm); and finally a discussion on recipe translations, interpretation and application ("Diz bu°ch sagt von gu°ter spise, daz machet die vnverichtigen ko°che wise" Von der Rezepthandschrift zur Interpretation" by Andreas Klumpp).

Of special interest is the paper regarding the Roman fort at Saalburg with its very long history in experimental archaeology and reconstruction. The oldest reconstruction at this archaeological site dates back to 1885, with the re-building of the defensive wall in the south-western part of the fort. Further steps were undertaken in reconstructing architectural remains of the main gate (1898), Principia, the granary and the south wing of the Praetorium (1906), the defensive wall with towers (1907), barracks for soldiers (1913), the western wing of the Praetorium (1977) and the north- and eastern wing of the same building (2009). Attention was dedicated equally to their exterior and interior. In some of the buildings, like the Principia, replica of floor-heating was established and set to function. Structures used for the production of various items were also made, including a pottery kiln, two different kinds of grain mills and a bread oven. Needless to say, items like clothes, shoes, jewellry, weapons and many others are also made and displayed at this fort. The quantity of experiments led to the production of a quantity of items, but also to a quantity of publications regarding everyday-life in a Roman fort, thus making the entire project and its outcomes really valuable not only for archaeologists, but also for broader general public.

Just like all of the previous issues of "Experimentelle Archäologie", this volume is a real treasure for all archaeologists and archaeology-related experts who deal with archaeological experiments, reconstructions and dissemination of information with the public. Although the geographical framework is focused on Europe, the time-span of the issue is broad (from early prehistory to roughly modern times). It enables insight into various studies and attempts conducted by experts and based upon reliable archaeological evidence. As experience teaches us, many of these attempts and experiments led to improvements in scientific interpretations, understanding artifacts in a fully different way and learning from the past.

Book information:

Weller, U., Lessig-Weller, T., & Hanning, E. (eds), 2016. Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2016, Heft 15, Unteruhldingen: Gunter Schöbel & Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der Experimentellen Archäologie e.V. European Association for the advancement of archaeology by experiment, ISBN: 978-3-944255-06-4.

Keywords

Country

- Germany