The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Ceramicists, Apprentices or Part-Timers? On the Modelling and Assembling of Peak Sanctuary Figurines

The question of who made peak sanctuary figurines has frequently been raised but seldom deeply examined. The assumption that the aesthetically refined pieces were carefully made by skilled ‘artists’ while the less visually pleasing ones were rapidly made by low-skilled ‘artisans’ has consequently endured. Revisiting these conclusions from a materially inclusive perspective that incorporates examinations on the process of figurine making, this study experientially and experimentally investigates what learning to model and assemble a medium-sized composite anthropomorphic figurine required and therefore what forms of knowledge and experience the task necessitated. Building on the observation of 60 novice participants’ experiences with figurine modelling and assembling, this analysis proposes that a range of differently trained and skilled individuals participated in figurine manufacture. Ultimately, in advancing a more nuanced perspective on the question, this paper shows how participation in figurine making may have varied from context to context and how assessing figurine makers’ level of skill is a complex endeavour contingent on a number of intangible factors such as training, psychological disposition and the artefacts’ function.

Who Modelled and Assembled Peak Sanctuary Figurines?

In this paper, I explore the pervasive, yet only partially investigated, question of who made peak sanctuary figurines. Peak sanctuary figurines are small anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay representations, found by the thousands at Cretan Bronze Age mountain sites, alongside a range of utilitarian ceramic vessels and, occasionally, ceramic votive body parts and models, metal objects, stone vessels and small pebble clusters. While broadly referred to in discussions on rural cult and Cretan Bronze Age religion more generally, the denomination ‘peak sanctuary figurine’ is in reality an umbrella term for a number of different figurine types which most likely dated to different phases of the Bronze Age.1 The archaeological record presently comprises: small to medium-sized2 free-standing pieces which principally date to the Protopalatial period (circa 1900-1750 BC) (Myres, 1902/3; Rutkowski, 1991; Peatfield, 1992; Morris, 1993, 2017; Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki, 2005) (See Figure 1) although some have been associated with the early phase of the Neopalatial period (circa 1750-1490 BC) (Rethemiotakis, 2001; Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki, 2005; Sphakianakis, 2012, forthcoming; Spiliotopoulou, 2019); small limb figurines contemporary with the aforementioned Protopalatial pieces (Rutkowski, 1991; Peatfield, 1992); miniature to small-sized3 pieces designed to be contained in vessels (Alexiou, 1967; Tzachili, 2011) or models (Karetsou and Rethemiotakis, 1990) which may date to both the Protopalatial and Neopalatial periods; and large4 pieces which effectively qualify as figures (Myres, 1902/3; Kourou and Karetsou, 1997; Rethemiotakis 1998, 2001) and which date to the Neopalatial, Postpalatial (circa 1490-1100 BC) and Subminoan (circa 1100-1000 BC) periods.5 These figurines and figures, alongside their accompanying assemblages have been interpreted as ritual in nature. It has been suggested that the small to medium-sized Protopalatial figurines were votive offerings which principally consisted of the inexpensive and disposable possessions of rural folk (Myres, 1902/3; Peatfield, 1992) and that the later and larger-sized pieces were portraits commissioned by wealthier individuals (Rethemiotakis 1997, 2001).

Owing principally to the limited amount of published material, academic treatment of peak sanctuary figurines has been sporadic and has predominantly yielded a number of isolated case studies. While close to fifty peak sanctuaries have been identified in Crete, and a number have been excavated, no complete collection has yet been made available.6 Only a selection of figurines, presented in publications and museum displays, has thus formed the basis of many interpretations on this type of artefact and on peak sanctuaries more generally. Perceptible, however, is a persistent interest in the figurines’ mode of production. Discussions have, by turns, addressed the structure and organisation of the craft, the environment in which it took place, the techniques and technologies employed in the figurines’ manufacture and the levels of specialisation the latter required (Myres, 1902/3; Platon, 1951; Rutkowski, 1991; Pilali-Papasteriou, 1992; Rethemiotakis 1997, 1998, 2001; Morris 1993, 2009, 2017; Zeimbeki 1998, 2004; Berg, 2011; Tzachili, 2011; Morris et al. 2019; Murphy, 2018,in preparation; Spiliotopoulou, 2019; Sphakianakis, forthcoming). While a number of varying hypotheses have been formulated on this matter since the artefacts’ initial discovery in the early 20th century, consensus currently stands over the perspective that the figurines, regardless of their type, were issued from a form of organised production, which was probably structured around a designated workspace, such as a workshop, and which was also likely related to pottery production (Pilali-Papasteriou, 1992; Zeimbeki, 2004; Morris, 2009, 2017; Morris et al., 2019; Murphy, in preparation).

Despite these recent contributions and advancements in the field of study, theories about precisely who made the figurines have remained somewhat static, especially in regards to the small to medium-sized pieces which are the most studied. While rarely articulated or even explicitly stated, underlying many accounts on the artefacts is the notion that the visually refined, anatomically detailed and colourfully decorated small to medium-sized figurines were made by highly skilled individuals described as “artists” (Myres, 1902/3, p.371; Rutkowski, 1991, p.51), while the less visually refined, anatomically detailed and colourfully decorated figurines were made by less skilled individuals portrayed as “potters” or “artisans” (Rutkowski, 1991, p.51; Pilali-Papasteriou, 1992, p.207) (see e.g. Myres, 1902/3; Rutkowski, 1991; Pilali-Papasteriou, 1992; Rethemiotakis, 1997, 1998, 2001). Moreover, often implied in these interpretations are the views that the refined figurines’ makers worked with advanced technological methods in vibrant, centralised or specialised workshops, while the simpler figurines’ makers worked with low forms of technology in small, independent, provincial or rural units.

By reason of their simple logic, these postulations have largely persisted. However, in the light of recent research and especially of materially-focused and experientially-based investigations on figurine production (see Morris et al., 2019; Murphy, 2018, in preparation), the reasoning outlined above appears somewhat reductive, especially where the less visually refined figurines are concerned. While I certainly do not dispute the fact that some figurine makers may have indeed been more adept than others, or that some workspaces may have benefitted from better equipment than others, this reasoning presently manifests a number of problems. First, it is evident that it was initially almost exclusively founded on appraisals of the figurines’ appearances, which were inevitably governed by the archaeologists’ modern aesthetic sensitivities. As well as reflecting a socio-culturally defined sensory bias, this approach therefore also provoked the problematic conflation of an object’s appearance with a craftsperson’s abilities. The reasoning under discussion effectively works on the assumptions that skill is invariably reflected by an object’s appearance and that skilled craftspeople always seek to produce visually-pleasing objects. It entirely neglects the artefacts’ compositional, constructional and structural qualities, and it fails to consider the forms and degrees of knowledge required for the successful completion of clay preparation, of the modelling and assembling of the figurines and of the objects’ firing. Consequently, the idea of what a ‘well-made’, technologically advanced and successfully decorated figurine consisted of has long been disproportionately based on aesthetic parameters. However, as a few, mostly recent, studies have demonstrated, the majority of studied peak sanctuary figurines were in reality manufactured with efficient techniques and are thus structurally sound and adequate, although their visual quality varies both from site to site and at a single given site (Zeimbeki, 1998; Morris, 2009, 2017; Murphy, 2018, in preparation).

Second, this reasoning divides artists from potters and artisans, but neither articulates the reasons for this distinction nor defines what these two titles precisely mean in the Aegean Bronze Age context. Moreover, this modernist distinction places these – apparently different – occupations on a hierarchical scale. Scaling is, however, unhelpful since it remains entirely unknown whether such distinctions existed in Bronze Age Crete and if they did, whether they were relevant to aptitude, social standing, to urban or rural location, to technological use, or to workspace type. Third, the reasoning outlined above entirely overlooks the possibility that the workspace in which the figurines were produced involved a number of differently skilled individuals and fails to consider that these individuals may have undertaken tasks in line with their knowledge and experience. The view that the person modelling and assembling the figurines was also in charge of their firing remains pure conjecture. In fact, a recent study on the artefacts’ chaîne opératoire revealed that the artefacts’ production involved a number of different technologies, requiring different forms of training and knowledge, in which a number of differently experienced and specialised individuals may have participated (Murphy, in preparation).

Furthermore, it is noticeable that most accounts adhering to the reasoning under discussion circumvent the fact that some figurines are better preserved than others. Some pieces, such as those from Petsophas, consequently appear to be of better quality than the very fragmentary and damaged pieces from Philioremos and Maza, while in reality, this may simply be an impression. It appears, especially in early accounts on the artefacts, that the figurines’ state of preservation and their quality were at times confused. Paint wears off fired clay especially when it is exposed to soil acids and to the extremes of mountain weather, and ceramic objects – depending on their composition and firing temperature – can severely suffer from abrasion provoked by natural phenomena (Schiffer and Skibo, 1989). It must also be noted that the way in which the artefacts were treated and stored after their excavation may have also played a role in this process. For example, following the excavation of Philioremos in 1966, the figurine fragments were placed by the dozens in large plastic bags, which were then tightly packed in plastic crates. The plastic-on-clay and clay-on-clay friction provoked by this mode of storage undoubtedly contributed to the artefacts’ surface damage. Thus, the possibility that the schematic and unpainted appearance of some fragments is due to wear, be it ancient or modern, cannot be ignored.

Last, it must be noted that visually refined, anatomically detailed and proportionate figurines tend to be associated with a later, early Neopalatial date than simpler looking figurines which are frequently dated to an earlier Protopalatial date. While in a number of cases (e.g. Kophinas, Piskokephalo, Vrysinas) this dating is founded on stratigraphic and ceramic evidence and is therefore indisputable, in other cases it is drawn from stylistic comparisons and, on occasion, from the premise that Bronze Age Cretans improved their rendering of the human body over time (Rutkowski, 1991, p.52). This perspective is problematic not only because it relies almost exclusively on assessments of appearance, but also because the use of an evolutionary approach overlooks the possibility that ‘simple’ appearances may have been deliberately preserved in later periods in order to, for example, perpetuate or honour a specific tradition.

In the light of the above, it is therefore evident that addressing the question of who made peak sanctuary figurines necessitates the use of a more systematic and critical approach, which can be developed and expanded over time as more archaeological material becomes available. For that reason, I analyse what learning to model and assemble a small-to-medium sized figurine requires by examining what forms of knowledge and experience were involved in the process. Although the tasks of modelling and assembling a figurine form only a small part of the whole production chaîne opératoire (Murphy, in preparation), they are here focused upon because, on the one hand, they have been frequently discussed and, on the other hand, they are the most practical to investigate on a small experiential and experimental scale, as opposed to material collecting or firing for example. Moreover, the examination of learning, knowledge and experience spurs the unpacking of previous categorisations of figurine makers as simply ‘skilled’ or ‘unskilled’. I undertake this investigation by running an experiment where participants’ experiences of modelling and assembling figurines are examined, compared and discussed. This approach allows me to test existing hypotheses on figurine manufacture and to explore new prospects through active engagements with the craft. Built on a careful analysis of archaeological evidence, this approach consequently allows for an analogical exploration of the process of figurine making alongside a closer observation of the material, technological and social parameters involved.

Investigating Figurine Modelling and Assembling

Examining knowledge and learning

Before detailing the experiment undertaken in this paper, it is necessary to briefly outline the current archaeological stance on the notion of knowledge. The specific type of knowledge under discussion here consists of craft knowledge. The long and complex history of research on the topic, defined by routine shifts from dichotomy to dialectic, demonstrates that for decades it was almost exclusively associated with practical matters and with the body and was consequently attributed a principally non-discursive and tacit character (Stig Sørensen and Rebay-Salisbury, 2013). However, an important paradigm shift, which occurred toward the end of the twentieth century and continues to govern many perspectives on the subject, proposes that craft knowledge comprises a number of different forms of apprehensions of the world. This type of knowledge is therefore presently perceived, in the archaeological and anthropological spheres, as a convergence of a number of cognitive and motor processes folded together, happening both in the mind and the body simultaneously, and resulting from both tangible negotiations between the body and material and less tangible socio-cultural processes (Dobres, 2000; Malafouris, 2004; Knappett, 2005; Ingold, 2013; Stig Sørensen and Rebay-Salisbury 2013). In this light, craft knowledge arises through embodied experience, following cerebral and corporeal engagement with the world through the senses. In portraying craft knowledge as a multi-faceted phenomenon developed over time through experience, this perspective subsequently draws attention to the continuous process of becoming knowledgeable. Such theoretical readings therefore suggest that craft knowledge does not consist of a fixed package of finite technical information that is acquired, but is effectively an experience, made anew on every occasion with each craft event.

Following directly from the above, it is at this point necessary to address the notion of skill. Skill, in the context of craft, refers to a degree of craft knowledge; in other words, to a proficiency in executing technical tasks (Bleed, 2008; Michelaki, 2008; Budden and Sofaer, 2009; Kuijpers, 2013, 2018). It is effectively deep sensory knowledge of materials, tools and the environment (Kuijpers, 2018). Thus, describing a craftsperson as skilled is a means of qualifying the person’s ability to understand how materials and tools are best handled while being able to successfully complete the task in practice in an optimal way. Skill therefore arises from a learning process which allows the individual’s competency in the craft to increase over time, through repetition (Roux et al., 1995; Harlacker, 2006; Kuijpers, 2013, 2018; Bleed, 2008). Skill is therefore difficult to treat archaeologically because it is not always immediately visually manifest (Kuijpers, 2018), and because it can manifest itself in different forms depending on context (see e.g. Gosden, 2013).

Examining craft knowledge in consideration of the theories outlined above consequently advances the investigation on peak sanctuary figurine production on several levels. First, this perspective allows for an essential shift in focus from the figurines in their final form to their process of becoming. In other words, in endorsing the view that figurines are the product of engagements of people with material and thus of lived sensory experiences, this perspective directly encourages and enables examinations on how the objects came to be, why, under which conditions and what roles aptitude and skill played in the process. It allows for the recognition of the fact that nobody starts off as a good craftsperson (or, at least, not as good as one may become following practice!): in order to produce a ‘good’ figurine, one must first produce a number of ‘less good’ figurines.

Second, examining figurine production through the approach outlined above draws attention to the context in which the craft was undertaken and thus to the network of social relationships involved therein. Craft knowledge, as is presently widely recognised, is maintained and validated through contacts and exchanges between individuals and social groups (Dobres and Hoffman, 1994; Dobres, 2000; Flad and Hruby, 2007). Rather than developing their knowledge in isolation, craftspeople, in most cases, learn through participation in specifically structured systems of interaction – between teacher and learner for example – and through their inclusion in a community of practice (Wenger, 1998; Minar and Crown, 2001). Furthermore, it is through these connections that less tangible aspects of craft, such as the values attributed to the activities and objects, are communicated. Indeed, alongside needing to be able to carefully observe the performance of the craft in order to learn it, learners must also be able to understand and appreciate what is the ‘right’ or the ‘wrong’ way to do something and what meaning their actions hold within their community (Michelaki, 2008; Budden and Sofaer, 2009; Stig Sørensen and Rebay-Salisbury 2013). Therefore, examining craft knowledge in this light allows for wider views on who might have been involved in figurine production and for considerations on whether participation in the craft was governed by or imbued with any perceptible cultural, social, economic, political or religious codes.

Third, as a direct result of the above, examining craft knowledge from this perspective draws attention to a salient aspect of the figurines which is little investigated in research on their production: the fact that they consist of ritual, and probably religious, paraphernalia. While this factor has been discussed in research on their consumption owing to their deposition in open-air ritual spaces and their conspicuous absence from domestic contexts (see e.g Myres, 1902/3; Rutkowski, 1991; Peatfield, 1992; Peatfield and Morris, 2012), the influence of belief and other cultural values in the artefacts’ production is seldom addressed. As was implied in the previous paragraph, it is very possible that religious values were already imbued in the objects prior to their use at the peak sanctuaries from as early as the beginning of their production. It is conceivable that even the materials bore special significance as well as the areas from which they were sourced. While these aspects are not archaeologically perceptible, they must be considered because they may have had an impact on certain choices made during the figurines’ creation. Choices may indeed have been dictated by other factors than simply practicality (Gosselain, 1999; 2000; Michelaki, 2008).

Overall, examining what forms of knowledge and experience were involved in the processes of modelling and assembling figurines allows for the conceptualisation of the craft as a more vibrant, living and constantly–but subtly–shifting activity influenced by a number factors such as knowledge, context, season, community and belief. This approach also facilitates the construction of a more intricate view of who may have created the objects and of how these people related to each other, rather than the perpetuation of an impersonal, hierarchical and polar image of the system alone. It allows for the consideration of the development of knowledge and experience, of change and of the progression from learner to teacher. Therefore, the perspective on craft knowledge adopted here encourages reflection on what different forms of knowledge and learning systems might have been involved in figurine making; on what material, socio-cultural and environmental conditions prompted the development of such knowledge; and on the role that less conspicuous factors such as aptitude and skill played in this process (Wallaert-Pêtre, 2001; Crown 2001, 2002; Creese, 2012; Wendrich, 2012; von Rüden, 2015).

An experimental approach

The experiment used to tackle the question raised in this paper is experience-based and involves participants. While falling under the wider remits of the experimental umbrella, the present study principally comprises the observation and evaluation of experiential data. In challenging the assumption that figurines were exclusively made by either ‘artists’ or ‘potters’, or by ‘high-skilled’ or ‘low-skilled’ hands, it uses the participants’ experiences as gauges for the examination of the forms of knowledge and experience required to successfully produce a figurine and for the consideration of the conditions in which such knowledge and experience develop. The involvement of participants has two principal advantages. One is that it allows the investigation, which is primarily concerned with the experience of craft knowledge development, to directly engage with the phenomenon under discussion. The other is that participant involvement allows for the observation and comparison of the results of multiple experiences. The latter thus offer a broader view of the subject of learning than my own, very specific, experience alone could provide.

Certainly, the approach is analogical. The participants’ experiences can, on no account, be compared to those of people living in the Bronze Age period of Crete. Clay held an important place in the latter’s lives: it formed the ground that they walked and worked, composed the objects they used on a daily basis and possibly also held their houses together. Moreover, as was mentioned above, clay–or the craft of working with clay–may have held a number of culturally-specific associations which entirely elude the 21st century researcher. Regardless, comparison is not the point of the experiment discussed here. Rather its aim is to explore, through the observation of participant experience, what material and practical parameters are necessary for the successful creation of a figurine and to accordingly further investigate and articulate the role that skill played in the activity.

The Experiment

The participants

Sixty participants were involved in the experiment. In order to maximise its potential, to preserve its focus on learning and to maintain control over variables, only individuals inexperienced in working with clay and unfamiliar with the topic of peak sanctuary figurines were selected to participate. None of the participants, who ranged between 18 and 21 years of age, had worked with clay since their childhood. Moreover, all were new to the discipline of archaeology, being first year students in Classics and Archaeology at the University of Kent. Furthermore, in order to ensure that the participants remained as uninformed as possible, the experiment was undertaken prior to the scheduled lecture on Cretan Bronze Age sanctuary sites and figurines that a number of students taking the Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology course would attend. None of the students were therefore familiar with the texts on the topic cited in this paper.

The figurines

As was clarified at the beginning of the paper, several different types of peak sanctuary figurines exist. The particular type under discussion here is the common and ubiquitous, free-standing, small to medium-sized, principally Protopalatial figurine, which is by extension the most studied. Figurines of this type are composite, formed of separately modelled body parts. They are decorated with a range of specific colours, usually black, red and white and are fired. Moreover, since practically all of these figurines were discovered in a fragmentary condition, it has been suggested that they were either deliberately broken or left to decay (see Myres, 1902/3; Peatfield, 1992; Murphy, 2018). The general similarities in appearance, construction and treatment exhibited by figurines at different sites imply that their producers adhered to certain overarching, island-wide standards (Murphy, 2019). It is nevertheless necessary to clarify that, despite these similarities, small to medium-sized peak sanctuary figurines (as is also the case for the miniature types, limbs and figures) are far from identical: they tend to stylistically, compositionally and possibly functionally differ, both from site to site and even at a single given site. As well as presenting its own geographical and material traits, each peak sanctuary also undoubtedly cultivated its ideologies and values and maybe even its own functions and belief system. Indeed, although these small to medium-sized figurines are here referred to in somewhat generalising terms, every site, and consequently every group–and potentially every subgroup (Morris, 1993)–of figurines presented its own idiosyncrasies.

For the purposes of the present study, I limit my examination to anthropomorphic figurines. The figurines employed as a basis for this experiment are from the peak sanctuary of Philioremos (See Figure 2), to which I was kindly granted access by Dr Evangelos Kyriakidis.7 The Philioremos figurines, as is the case with those of most peak sanctuaries excavated to date, are in a very fragmentary condition. Not a single small to medium sized anthropomorphic body could be reassembled in full. Nevertheless, drawing on similarities in the material composition, firing, manufacture technique and proportion presented by specific fragments, I was able to reconstruct a number of the different figurine types that were once deposited at Philioremos (See Figures 3 and 4). These reconstructive replicas, alongside drawings and photographs of the original fragments, formed the examples upon which the participants modelled their experimental pieces.

In order to best control the experiment, I chose to only use two specific reconstructed figurines: a male and a female example. The male figurine is of a very popular type which has also been identified at other Protopalatial peak sanctuaries such as Petsophas (Myres, 1902/3; Davaras, 1982; Rutkowski, 1991) and Maza (Platon,1951), to cite a few examples. The figurine stands erect, with both hands placed on the chest and with the legs joined. The eyes and ears are rendered with clay pellets, while the hair and accessories such as the belt and dagger are rendered with strips of clay (See Figure 5). The construction method employed for this piece, as traces on the Philioremos fragments indicate (see Berg, 2011), bears strong similarities to that observed on the figurines from the aforementioned sites (see especially Myres, 1902/3). The figurine was made in three main structural parts: the upper body (head and torso), the legs and the base. For the upper body, a solid thick cylinder of clay was modelled into a sphere at one end to form the head and was given concave recess at the other (at waist level) so as to accommodate the lower body. The legs were also modelled from one long solid cylinder of clay, folded over into a ‘U’ shape and of which the upper part–designed to be inserted into the torso–was lightly pinched into a conical point. The base was shaped into a rectangle or circle from a separate piece of clay and two recesses were pressed into it to accommodate the legs (Berg, 2011; Murphy, 2018) (See Figure 6). Experimentation with figurine modelling and assembling, undertaken as part of a wider project on these artefacts’ production (Murphy, 2016, 2018, in preparation), demonstrated that the success of the construction process depended on adherence to a specific protocol. The lower body and base were modelled and assembled, then left to harden. Assembling the upper body and lower bodies immediately after modelling would have caused the legs to sag or slump. In order to ensure the efficient joining of the upper and lower bodies, however, the clay of the very upper part of the legs–designed to be inserted into the waist socket–had to remain slightly damp, and thus it is hypothesised that it was covered with a damp piece of textile. In the meantime, the upper body was modelled.8 Only once the clay forming the legs reached a leather-hard state were the upper and lower body pieces assembled, following the application of some wet clay to the socket. Finally, the arms, facial details, hair and accessories were modelled and applied to the figurine.

The reconstructed female figurine employed in this experiment also consists of a common type, which bears close resemblance to pieces discovered at Petsophas (Myres, 1902/3; Rutkowski, 1991), Atsipadhes (Peatfield, 1992; Morris, 1993), Prinias (Davaras, 1982; Morris et al., 2019) and from the Metaxas Collection (Pilali-Papasteriou, 1992). The figurine, supported by a large bell-skirt, stands with both hands over the abdomen. Its head is adorned with a hat, the upper back with a peak-back collar and the waist with a belt (See Figure 5). The construction method employed for this piece was also observed on the pieces from the aforementioned sites (see especially Myres, 1902/3; Morris et al., 2019). Like the male figurine, the female figurine was made in three main parts: the head and hat, the torso and the bell-skirt. The head, hat and neck were modelled from one ball of clay, pressed on one side to render the hat and pinched at the other to form the neck. The torso was formed from another piece into which a hole was created at one end to accommodate the head and modelled into a tapering peg at the other end so as to be inserted into the bell-skirt. The bell-skirt, modelled from another piece of clay, was rendered by pinching and smoothing out a conical lump of clay and perforating a socket hole in its dome (See Figure 6). As was the case for the male figurine, a protocol was also followed for the female figurine’s construction. The bell-skirt was modelled first and left to harden. The head and torso were then created and joined. Only once the skirt was leather-hard were the upper and lower body parts assembled. Finally, joints were carefully smoothed over and the arms, facial features and accessories were applied.

Repeated experience with replicating small to medium-sized figurines allowed me to note that in reality the techniques employed in the objects’ construction only require a very limited set of gestures and that the latter are repeated for different purposes throughout the process. These gestures consist of rolling, smoothing, pinching and pushing clay. Moreover, it appears that assembling techniques are also recurrently used for different pieces (e.g. zoomorphic and anthropomorphic, male and female). Consequently, it is noticeable that although the female figurines flaunt a more complex appearance than the male figurines, their creation actually involves the same types of gestures. Accordingly, it is important to remark that as well as crafting my reconstructed pieces with the same techniques, I also attempted to meticulously replicate traces – apparent on the original artefacts – indicative of manufacture methods, such as finger impressions, on my copies.

The tasks

I divided the 60 participants into four groups of 15. Since none of the participants had worked with clay during their adult lives, I was not able to assess who may have been talented and thus the groups were formed at random. Two of the groups (1 and 3) were instructed to produce copies of the female figurine, while the other two (2 and 4) were instructed to produce copies of the male figurine. I assigned each group a different task and instructed them in two different ways. I instructed Groups 1 and 2 to model and assemble their figurines by drawing on the information provided by illustrations and photographs of the original Philioremos fragments and my reconstructive replicas, which they were invited to handle. I offered the participants no additional help, but I encouraged them to confer with each other. I directly showed Groups 3 and 4 the process of figurine modelling and assembling. I supplemented the demonstration with oral descriptions, technical advice and brief commentaries on the material qualities of clay. I also assisted the participants during their experience. Illustrations and photographs of the original pieces, alongside my replicas, were also made available. All groups were required to complete their objects within the space of 90 minutes. The material with which the participants worked consisted of semi-coarse and malleable, but fast drying, modelling clay.9 It must be noted that the difference in clay colours apparent in the photographs relates to the clay origin and firing rather than to texture. None of the participants were required to paint their figurines. The experiments with all four groups were repeated exactly a week later, under the same conditions.

The experiments with Groups 1 and 2 were structured along the principles of trial-and-error learning while Groups 3 and 4 worked on the bases of scaffolded learning. The former embraces the value of discovery and the concept that people learn by doing. There is more consciousness and criticism in the process–through this approach one really learns how to learn (Ingold, 2013). The latter provides the learners a more controlled and error-preventive form of instruction, which minimizes material wastage and decreases the amount of time that the learning process requires. However, contrary to the trial-and-error approach, which offers greater freedom, scaffolded instruction reduces personal discovery and delays the exploration of individual creativity (Greenfield, 2000; Crown 2001, 2002; Wendrich, 2012, Wallaert 2012; Budden and Sofaer, 2009). Although this categorisation of modes of learning may appear somewhat artificial because craft training in reality involves a broad range of merged pedagogical approaches (Michelaki, 2008; Kohring, 2013), it is here employed for the sake of analysis. This division allows for the observation of the different conditions under which learning to make a figurine can occur.

Given that I instructed all four groups and demonstrated the task to Groups 3 and 4 myself, it is necessary to note my own experience and capacities in working with clay. My experience with began during my teenage years as part of my training in an art academy. Ceramics were my least preferred class: I did not have an aptitude for working with clay like I did with drawing, and I therefore struggled to produce anything I was satisfied with. I nevertheless reached the required basic level of competency and completed the class because it was an obligatory part of my course. My interest in ceramics was truly kindled in my twenties, when I began my doctoral research on peak sanctuary figurines. Since then I have worked extensively with clay, taken classes, consulted with professional ceramicists and practiced regularly with slab-building, moulding and wheel throwing in order to improve my performance. While my knowledge and experience on no account equate with those of a professional ceramicist, I am capable of instructing novices in simple tasks, especially where the creation of small, hand-made objects is concerned.

Recording the experimental data

Contrary to pottery, no conventions for recording technological traces present on prehistoric handmade figurines, and thus for exploring their makers’ levels of skill and expertise, have yet been established. In fact, the way in which these parameters have been measured is somewhat arbitrary, especially in the case of Cretan Bronze Age figurines. Except for the few experimental studies undertaken in this field (Murphy, 2018, in preparation; Morris et al., 2019; Gesell and Saupe, 1997), it appears that assessments have been based principally on the figurines’ appearances, that is, on the care and detail dedicated to their final surface treatment. Presently, this approach is problematic: not only does it limit the study of the original pieces, it also complicates experimental research.

Nevertheless, drawing on previous experience with producing peak sanctuary figurine replicas, I based my assessment of the participants’ performance in modelling and assembling their figurines on the following set of criteria (also employed in the analysis of the original artefacts): success in maintain their objects in an upright position (not sagging or leaning back), success in creating stable bases (not needing to be supported), use of efficient modelling techniques, success in securely assembling body parts, correct detail application, overall understanding of the order in which the operations were to be carried out and resemblance to the original piece.

The way in which the participants’ performance was recorded was through a graded system ranking from 1 to 5. It must here be noted that the grades were attributed to the participants’ work in consideration of the fact that they were all novices. Learning a craft is not a simple process, but rather a complex one which requires time (Wendrich, 2012; Høgseth, 2012; Knappett, 2016). If the experiment had been undertaken with experienced participants, the grading would have been different. As an additional recording measure, each participant was required to briefly comment on their experience with special attention placed on how they felt in regards to the tasks’ difficulty, if they felt inclined to make more figurines following their first experience and if they believed they could improve their performance.

Results

Groups 1 and 2

The first experiments undertaken with Groups 1 and 2 yielded mediocre to poor results. Errors occurred especially in construction, specifically in how the pieces were joined and in the order in which the different operations – especially the assembling – were carried out. Most participants began the process by modelling the figurines’ heads and finished by modelling the lower bodies thus causing the latter to sag or slump. Only one participant from Group 1 and two participants from Group 2 chose to work with a bottom-up method. Upon realising that they would not achieve structurally or visually accurate copies of the example pieces, however, most participants chose to complete the task by using their creativity. For example, the students from Group 1 either systematically reduced the lower body part in size, thus producing disproportionate figurines, or reinforced the bell-skirt with additional clay, thus effectively creating solid instead of hollow lower bodies. One participant even created a pair of legs to support the figurine and attempted to conceal the trick with a superficial skirt (See Figure 7, rightmost figurine). It is additionally noticeable that some participants attempted to salvage their structurally poor figurines by putting effort into the rendering of their appearances (see e.g. rightmost figurine on Figure 7 and middle figurine on Figure 8). Overall, it is clear that modelling and assembling a male figurine came more naturally to the participants than modelling and assembling a female figurine, despite the fact that the procedure and gestures required for the completion of both types of figurines are very similar. The visual lure of the bell-skirt, hat and peak-back collar distracted and confused the students. With this first experiment, it was very difficult to judge which participants, if any, possessed an aptitude for working with clay. A small number of participants expressed frustration with their lack of competency. Affected by this impression, they expressed less excitement at the prospect of participating in the second round of experiments.

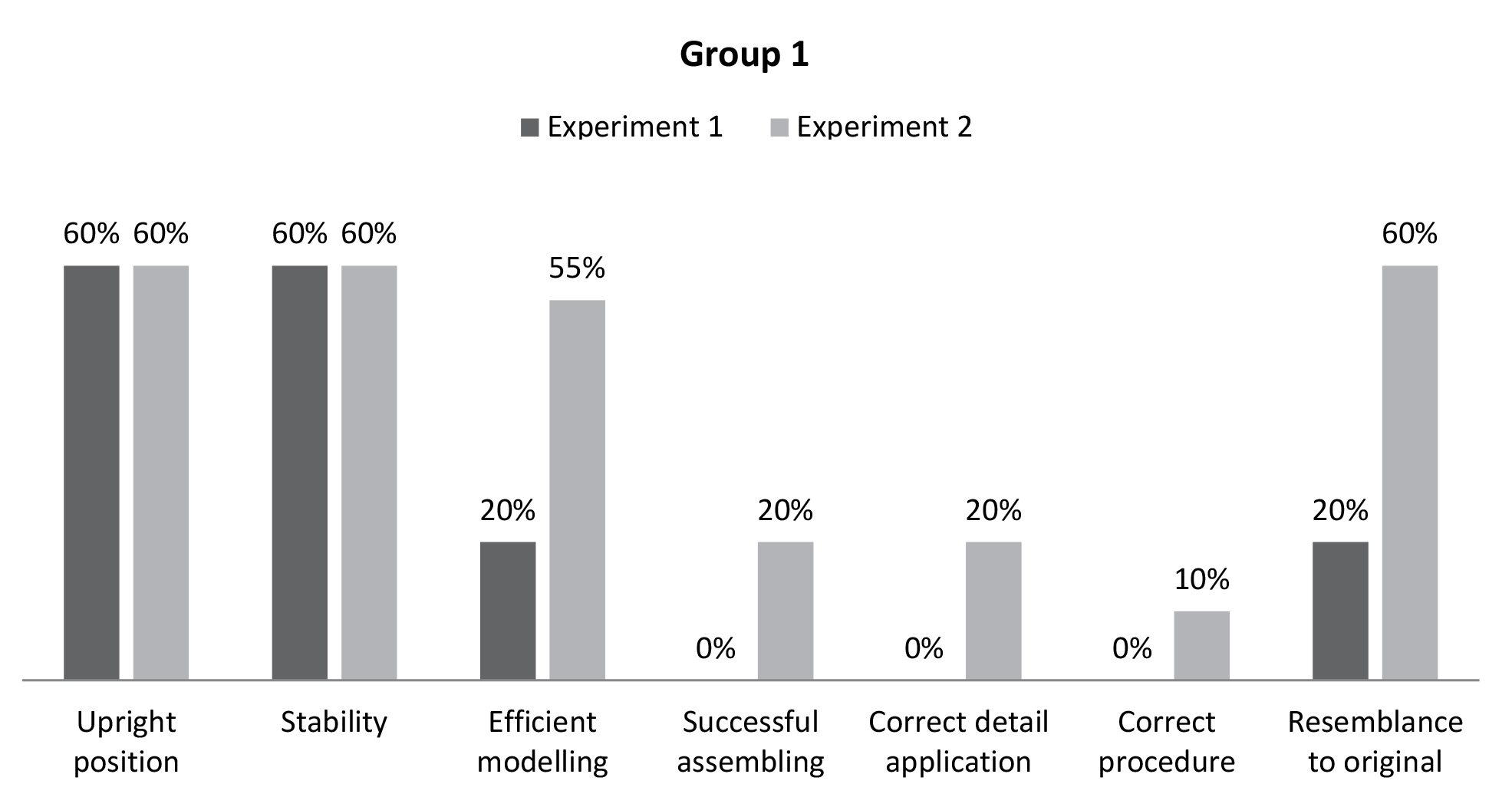

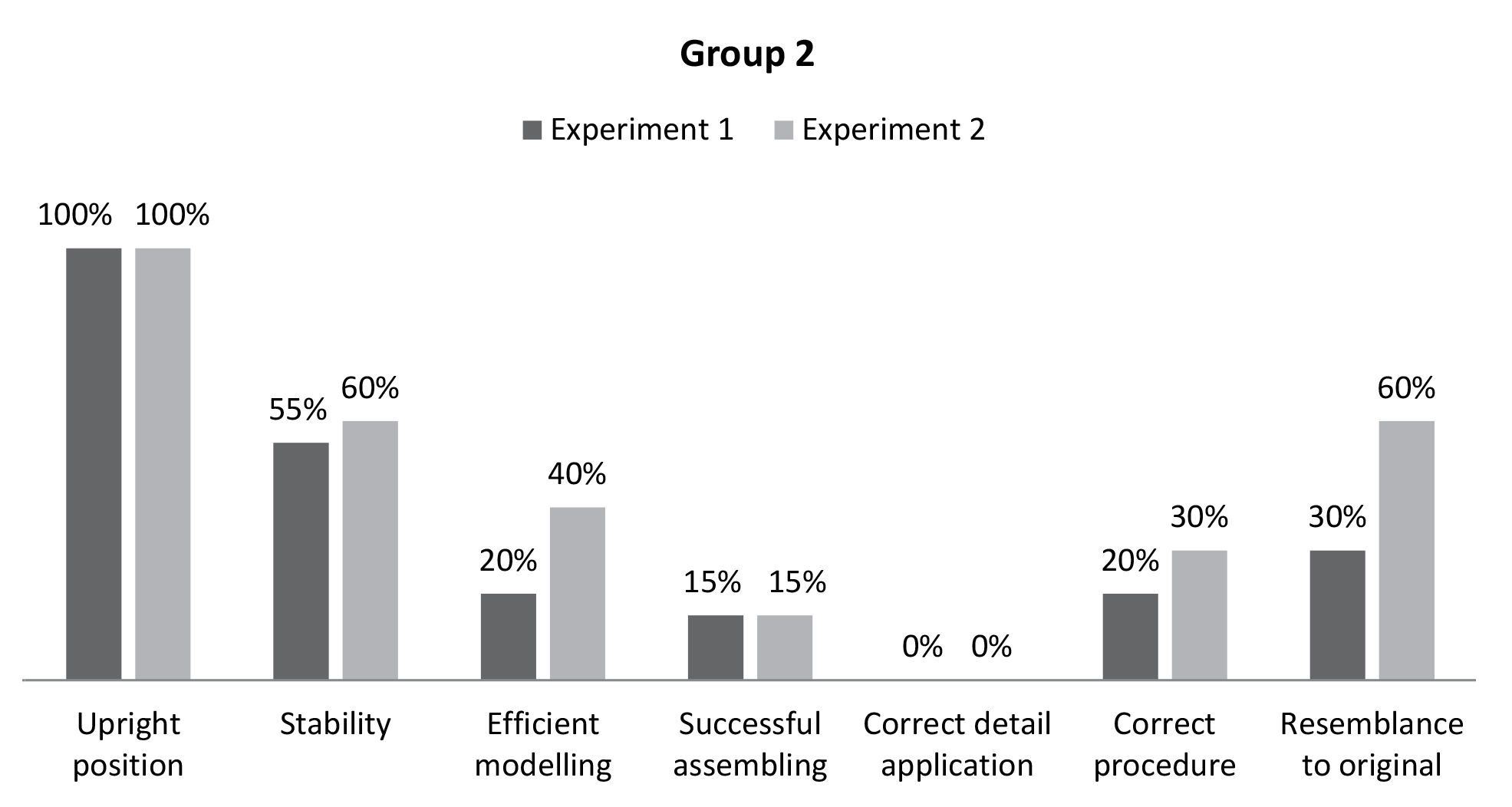

The second round of experiments, held a week later under the same conditions, yielded better results. It is evident that some of the participants had reflected on their previous experience and had devised better ways of completing more accurate copies. However, to my knowledge at least, they had not done any research on the topic or practiced with the task. More specifically, participants demonstrated a much better understanding of the structure of the process and demonstrated much more awareness of how to work with the material. Having experienced the process once, they were thus able to project what their second experience would involve and consequently better picture the consequences of their engagement with material on their final object. The sense of discovery and comprehension experienced by the participants on this occasion was palpable. It also became very clear that the students had developed the ability to abstractly project what their approach and gestures would result in and the effect these would bear on the objects in their final form. Moreover, it became clearer which participants had an aptitude for the task: they executed the activity with more exactitude, demonstrated an understanding of the objects’ structural requirements, rendered the figurines’ surface features with more accuracy and even assisted other participants in successfully completing the task. Of course, the final results of the second experience did not compare with the original figurine pieces or with my replicas, yet it is evident that with experience and critical reflection, the participants’ performance considerably improved (See Graphs 1 and 2). Finally, the commentaries provided by the participants following their experiences reveal that the majority enjoyed engaging with clay but, most crucially, enjoyed noting their improvement with the task over time. The previously reluctant students, while still not particularly enthused by their performance, stated that their second experience was slightly better than the first and that they were grateful for support from their peers. It must nevertheless be noted that their figurines remained the worst of the whole group, both in terms of structure and in appearance.

Graph 1. Experiments 1 and 2 with Group 1.

Graph 2. Experiments 1 and 2 with Group 2.

Groups 3 and 4

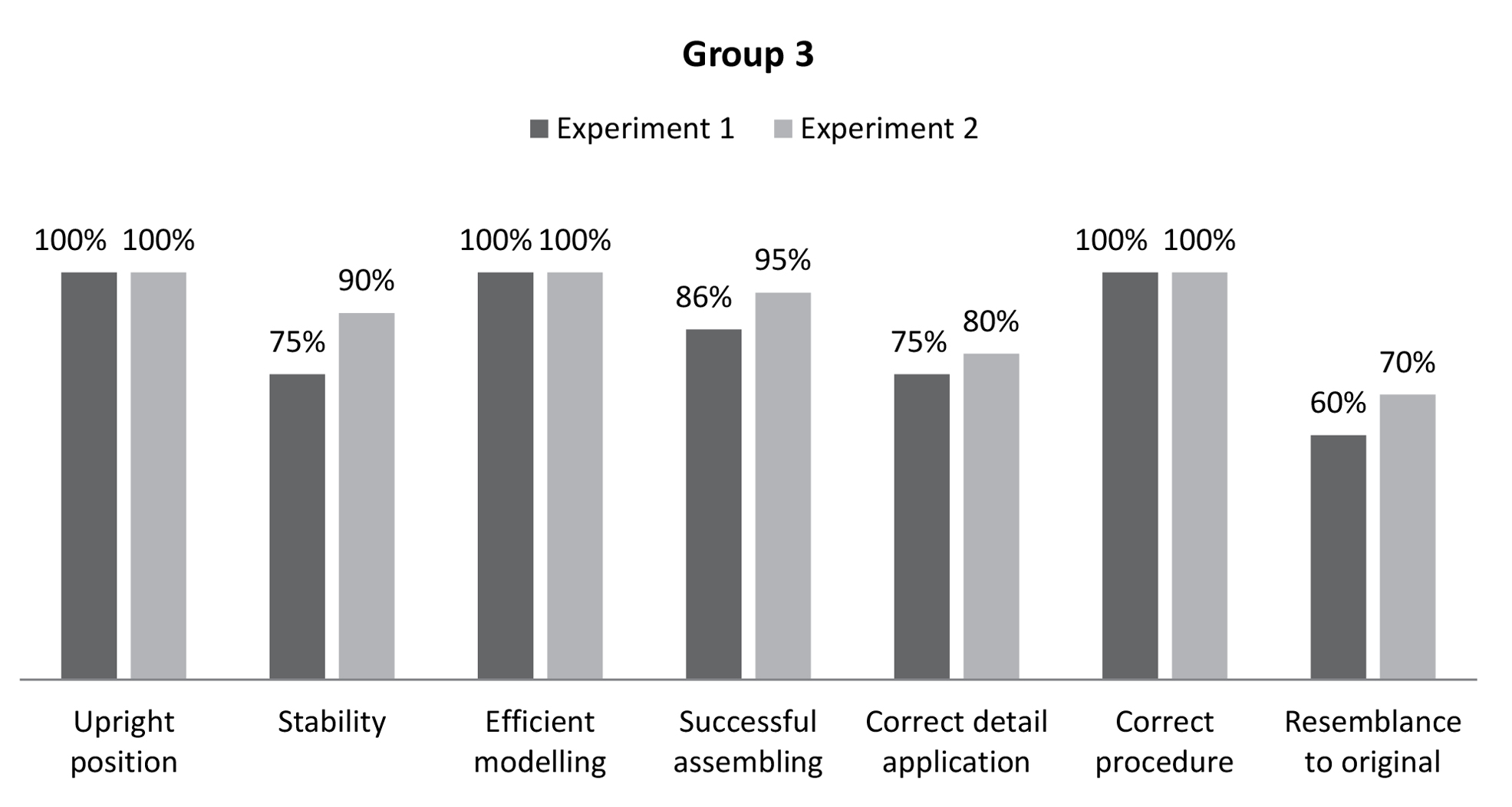

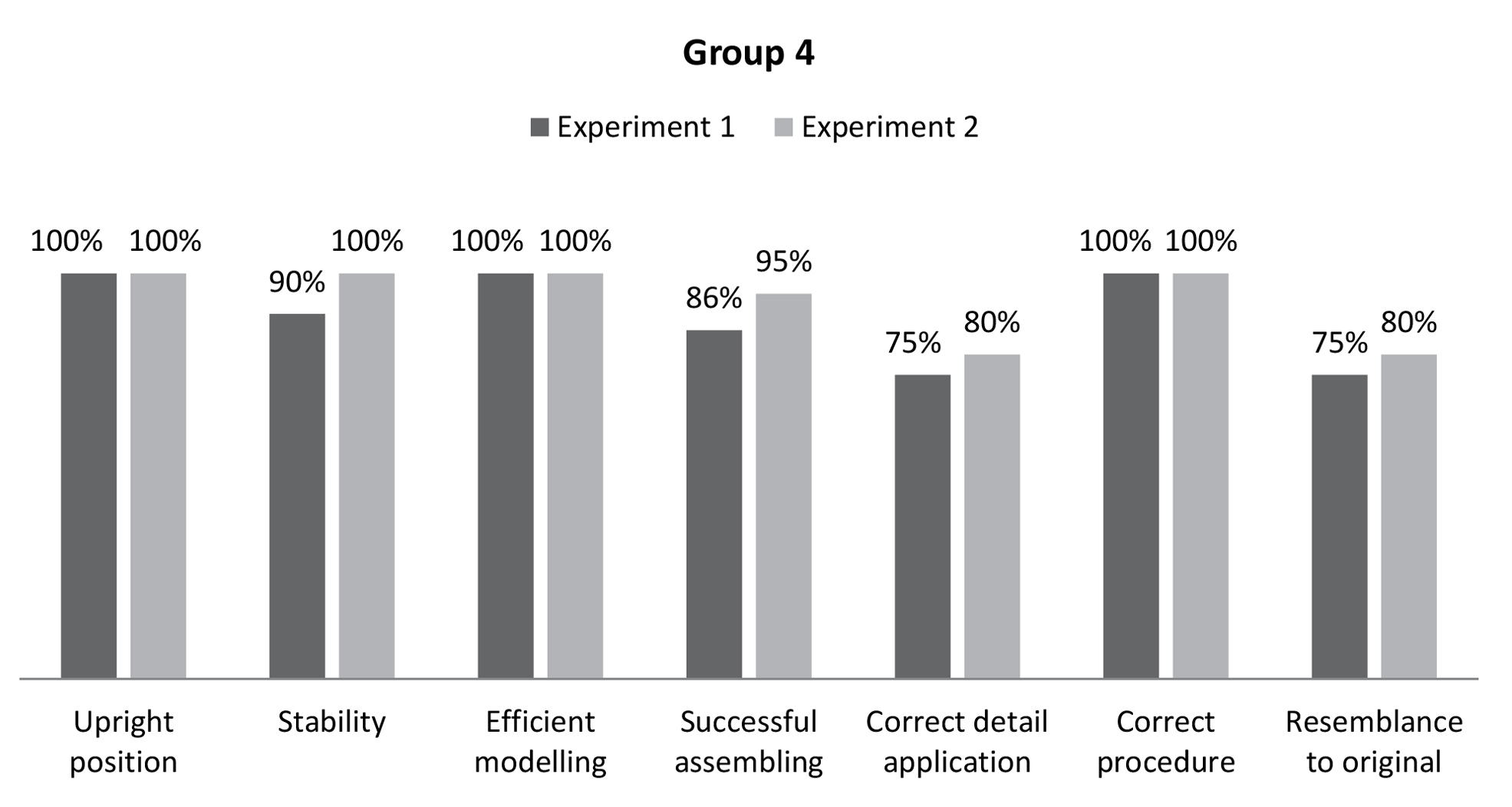

As was expected, the experiments carried out with Groups 3 and 4 yielded better results than those undertaken with Groups 1 and 2. Having been attentive to the instructions and demonstration provided, the participants successfully produced structurally and visually sound figurine copies. Interestingly, in contrast to the participants of Groups 1 and 2, the participants of Groups 3 and 4 expressed less concern with the neatness of their figurines’ appearance as they did with the accuracy of their construction, although their copies’ appearances were all very acceptable. An evident increase in attention to and success in the rendering of surface detail was nevertheless noted during the second round of experiments with Groups 3 and 4. Participants clearly improved in their performance through practice (See Figures 9 and 10 and Graphs 3 and 4). Direct teaching established the context and situation in which individual learning could take place and effectively set the terrain for the participants to become knowledgeable. It must, however, be noted that the creativity and imagination of participants of Groups 3 and 4 were less prompted than those of the participants of Groups 1 and 2. Rather, participants were cautious to fit within the experiment’s defined requirements. Aptitude for the task nevertheless also became evident in the way some participants intuitively understood how much wet clay to apply to the joining sockets and how to render the figurines’ facial features. Overall, the students expressed satisfaction with both their method of instruction and their own performance and productions.

Graph 3. Experiments 1 and 2 with Group 3.

Graph 4. Experiments 1 and 2 with Group 4.

Parallel workshops

The results of a few other peak sanctuary figurine-making workshops held during the last decade are worth a brief mention here. While not all structured as experiments, the outcomes of these events are pertinent to the present discussion. Most relevant is a figurine-making workshop that Mr Vassilis Politakis and I collaboratively ran in the modern village of Gonies (situated below the peak sanctuary of Philioremos).10 The event, consisting predominantly of an experiential, educative and community-engagement session for local inhabitants and students, was not designed as an experiment and thus was not as formally structured as the above. Nevertheless, the participants were shown how to model and assemble the same figurines used in the experiment discussed in this paper. They were provided with clays composed of local materials (similar to those observed on the original Philioremos fragments), and their figurines were then fired in a handmade kiln dug into the side of a soil bank, just outside the village. The participant’ experiences in modelling and assembling figurines were very similar to those reported above: when guided, they were able to produce satisfying copies of the objects they were shown. Also of direct relevance here are several other figurine-making workshops organised and run by Dr Christine Morris and Dr Brendan O’Neill with figurines from the peak sanctuary of Prinias (Morris et al., 2019). Also held as both experiments and public engagement activities, these events yielded similar results to the above in terms of participant performance.11

Overview

The primary observation to be drawn from the experiments outlined above is very simple: with attention to detail, observation, repetition and time, even a person inexperienced in working with clay is capable of developing the ability to make a figurine. The experiment therefore demonstrates that learning how to complete the task does not require aptitude, although the latter certainly quickens the process and improves the results. Moreover, with adequate scaffolded instruction, the learning process is direct and rapid. The results reported above nevertheless also show that learning through trial-and-error is possible, even though it requires more time, still necessitates a basic understanding of how to work with clay and of the clay’s material qualities and is materially more wasteful. Finally, the experiments also demonstrated that in the latter case especially, interaction between participants enhanced their performance.

It can thus be deduced that it is neither difficult to learn how to model and assemble a small to medium sized, composite, free-standing peak sanctuary anthropomorphic figurine, nor is it difficult to successfully complete the task following practice. Drawing from these observations, it can consequently be concluded that, from a practical perspective, becoming skilled in figurine modelling and assembling is therefore not a complex process and that, other than repetitive exercise, it does not require extensive knowledge in ceramic crafts. In other words, it is not necessary to be an experienced ceramicist to successfully model and assemble a figurine. The knowledge that an experienced ceramicist usually demonstrates, such as familiarity with soil sources, clay material qualities, the ability to levigate and wedge clay, the ability to efficiently use the wheel or rotative device, knowledge of slip composition and decorative techniques and the ability to successfully run a firing, by far exceeds what is necessary for the modelling and assembling of a figurine.

Returning to the Bronze Age, what can therefore be analogically deduced from the above in regards to who may have been involved in the task of figurine making four millennia ago and to how skilled these individuals were? To begin with, it is evident that as is the case for the experiment’s participants, it was not necessary for Bronze Age Cretans to be ceramicists in order to successfully model and assemble a composite, small to medium sized figurine. In fact, this particular task would have been much easier for a person living during the Middle Bronze Age of Crete to develop than it is for a 21st century urban-dweller because, as was mentioned above, clay formed an important part of Cretan prehistoric daily life. It therefore remains unclear what type of training these figurine makers would have received, if they did indeed receive any at all. While the experiment’s participants for the most part lacked basic knowledge of clay’s material qualities and of how to work with the medium, and thus had to be taught, it is possible that such knowledge formed an essential part of the prehistoric motor and cognitive repertoire. Two possible scenarios for the structure under which the prehistoric figurine makers developed their knowledge of figurine modelling and assembling consequently arise. The first proposes that the figurine makers were formally trained: like the experiment participants, they were shown the figurine making procedure directly during a specific instruction event. The second scenario proposes that the figurine makers were not formally trained: they learnt the craft informally through “impregnation” (Michelaki, 2008, p.373). This form of learning would have occurred, over time, following immersion in a community of practice or through contact with people knowledgeable in the craft. Immersion, however, did not necessarily have to take place within the workspace environment: it may have been communicated through play during childhood, through participation in daily activities during adulthood, during meals or any other social occasion.

It is, of course, currently impossible to assess which scenario is the most likely, given the general shortage of archaeological information available about peak sanctuaries. It is certainly conceivable that both existed and that the situation differed from site to site, production unit to production unit and period to period. What is evident, however, is that these scenarios are contingent upon the broader context in which the task of figurine modelling and assembling took place: on whether developing the knowledge to carry out this task was an end in itself, or if it was part of a broader ceramic craft learning process. In other words, the structure under which the figurines were made depends on whether or not the figurine makers were involved in other tasks involving ceramics, such as paste preparing, vessel making, wheel-throwing and firing, which did require a minimum training period in order to be successfully carried out. These observations, and the various possibilities they entail, consequently complicate and considerably deepen the present exercise of identifying who may have been involved in figurine making. In exposing the salience of context, these observations add new parameters to the equation and thus preclude the formulation of a single clear-cut answer to the question. Three possible suggestions as to who modelled and assembled peak sanctuary figurines are therefore advanced below.

Ceramicists, Apprentices and Part-timers

In consideration of the points outlined in the previous section, my suggestions about who made peak sanctuary figurines are structured in line with the broader context in which the task of figurine modelling and assembling took place. My first two suggestions–that the figurines were made by ceramicists and apprentices–are built on the postulation that these individuals were trained, or were in the process of training, in the broader craft of ceramics. Figurine production was not the end point of their engagement with clay. My third suggestion–that the figurines were made by part-time assistants–is modelled on the hypothesis that these individuals only engaged with clay for this specific task. Their main occupations lay elsewhere than in the craft of ceramics. These individuals may have thus not been as formally or directly trained as ceramicists and apprentices were.

A ceramicist’s business

The first suggestion I advance here is the most obvious: the figurines were modelled and assembled by experienced ceramicists. Being knowledgeable in the broader craft of ceramics, ceramicists would have completed the task under discussion with ease, speed and accuracy. It is probable that they also controlled the other stages of figurine production, such as material collecting, clay preparing, artefact decorating and firing. Moreover, being both experienced in working with ceramics and closely acquainted with the socio-culturally defined rules potentially surrounding the craft, ceramicists would have been capable of producing objects which met the exact demands of their users. It is conceivable that figurine production was a seasonal side activity for these experienced individuals, who may otherwise have mostly focused on producing heavily demanded utilitarian vessels.

In the light of the above, it is therefore possible that the ‘wheel-thrown’12 bell-skirts of some of the Petsophas female figurines (Rutkowski, 1991), which necessitate the use of a complex technology, were made by ceramicists. While simple in appearance, a small hollow cone is not the easiest shape to throw on the wheel or any other rotative device. It is considerably more complex to create than a cylinder, for example, which embodies the foundational principles of rotative device forming and which apprentices would have certainly practiced on a regular basis.

An apprentice’s responsibility

The next possibility is that the small to medium sized composite figurine makers were apprentices working with experienced ceramicists. These individuals would have been involved in a training programme, enabling them to eventually become ceramicists themselves. Certain aspects of figurine modelling and assembling indeed bear strong similarities to exercises and responsibilities typically given to learners. First, the gestures and techniques employed in the objects’ modelling and assembling are identical to those used in the modelling of vessel handles, spouts and plastic decoration and in their joining to vessels. Rolling out and bending a cylinder of clay to form a pair of male figurine legs requires the same attention to malleability, pressure and rhythm of movement as rolling out and bending a cylinder of clay for a handle. Modelling a female figurine’s peak-back collar and headdress require the same smoothing gesture and delicacy that modelling a spout does. Joining the figurines’ body parts and applying surface details such as pellets for eyes and strips for hair require the same use of slip or wet clay as a binding agent, the same application of pressure and the same finishing smoothing as joining handles, spouts and plastic decoration to a vessel’s body. Owing to these tasks’ relative simplicity, but also to the fact that they crystallise the basic principles of how to work with clay and how to create a solid composite piece, they are often given to apprentices as a training exercise (Budden and Sofaer, 2009; Wendrich, 2013; Knappett, 2016).

Second, the small to medium sized figurines studied here correspond size-wise to the type of objects that apprentices commonly begin actively producing (Arnold, 1985; Rice, 1987; Michelaki, 2008; Budden and Sofaer, 2009). Creating small to medium sized objects demands less dexterity, technological knowledge and experience than creating either miniature or large objects does because the small to medium sized object is made in proportion to the maker’s hands’ size. Such practice is observable on the figurines: some of their features, such as their eye sockets, are proportionate with the size of the average human finger impression. Thus, the figurine maker would not have had to worry about scale and proportion and could instead focus on correctly carrying out the modelling and assembling process.

Consequently, the task of figurine modelling and assembling can here be regarded as a skill-building opportunity. Not only would leaving this task to apprentices have enabled the latter to exercise their knowledge, it would have also allowed them to practice techniques they would employ in their creation of other clay objects. Moreover, taking responsibility for a task with ‘real life’ consequences would have certainly offered the apprentices an additional important learning opportunity and a chance to prove their capabilities. Of further consequence is the fact that as well as being useful for the learners themselves, assigning the task of modelling and assembling figurines to apprentices during times of heavy production would have relieved the experienced ceramicists of a time-consuming responsibility. The latter would have thus been free to work on more technologically-demanding tasks such as clay levigation and paste preparation, wheel or rotative device throwing, or firing.

Ultimately, as the experiments outlined above demonstrate, developing the knowledge of how to model and assemble a peak sanctuary figurine is not excessively demanding but is considerably enhanced by direct teaching. The existence of an apprenticeship structure within the peak sanctuary figurine production system is therefore both theoretically and materially plausible despite not being presently archaeologically traceable. Not only would such a structure have enabled young potters to rapidly become more efficient in their craft, as well as produce less material waste, it would have also considerably facilitated the communication, if not inculcation, of the social, cultural and possibly religious values associated with the objects and the craft (Childs, 1998; Wallaert-Pêtre, 2001; Flad and Hruby, 2007; Stig Sørensen and Rebay-Salisbury 2013; Wallaert, 2012). Moreover, an apprenticeship is effectively also a means for controlling knowledge: it ensures the perpetuation of specific material, conceptual and cultural standards. Apprentices initially learn to see, feel, understand, perceive and believe in a generally similar way to their teachers, although in many cases they later develop their own philosophies of the craft. It is, of course, currently impossible to verify this suggestion, but acknowledging its possibility endorses new conceptualisations on the craft and opens new avenues of research. Similarly, while it is at present very difficult to assess whether figurine modelling and assembling–and, in fact, the wider process of the figurines’ production–was governed by any specific social, cultural or religious codes, it is an interesting possibility to consider. Indeed, the repetitive and fairly simplistic character of the gestures employed in the figurines’ modelling and assembling lends itself perfectly to the establishment of meaningful ritualised action (Gheorghiu, 2010).

The contribution of part-time workers

While relating the task of figurine modelling and assembling to ceramicists or apprentices offers a convincing answer to the question raised in this paper, another, less obvious, possibility must also be considered. Building on a comment advanced by Pilali-Papasteriou about part-time figurine makers (1992, p.151), I propose that peak sanctuary figurines might have also been modelled and assembled by individuals who were not directly involved in ceramic crafts on a daily basis, but who nevertheless participated in the task as assistants and helpers during periods of heavy production. These individuals may have principally practiced other crafts such as metalworking, or altogether other occupations such as shepherding. As was discussed earlier, their training in the task may have been less formally structured than that experienced by ceramicists and apprentices, and in any case, it would have certainly been much less extensive. Finally, it is possible that these part-timers were supervised by the apprentices during their participation in the production event. As my experience with the experiments outlined above demonstrates, I did not need to have developed the same knowledge as a professional potter to successfully communicate figurine modelling and assembling techniques to my students.

Skilled, Low-skilled, or Specialised Figurine Makers?

The suggestions advanced above about who might have modelled and assembled small to medium sized peak sanctuary figurines demonstrate that a number of differently trained, and thus differently skilled, individuals may have participated in the task. In depicting a more complex image of the situation than previously, these suggestions certainly also influence how skill can be discussed in relation to the activity.

Earlier postulations that peak sanctuary figurine makers were low-skilled or high-skilled are therefore relative and entirely dependent on the context in which the figurines were made. The suggestion that these individuals were low-skilled (Pilali-Papasteriou,1992; Rethemiotakis 1997, 1998, 2001; Zeimbeki, 2004) is not incorrect if it refers to part-time workers within the broader craft of ceramic production. Indeed, the part-time workers mentioned above were not skilled ceramicists. They were only capable of modelling and assembling figurines and thus only had very limited experiences of working with clay. The suggestion that figurine makers were low-skilled is, however, problematic if it refers to the abilities of experienced ceramicists within the specific task of figurine making. As was discussed earlier, it is possible that figurine makers abided by the rules imposed by the peak sanctuary rituals or served the demands of the figurine users. It is risky, in this context, to assume that figurine modelling and assembling represents the extent of one’s skills.

Moreover, the study carried out in this paper demonstrates that as well as being relative, the development of skill can be influenced by a number of factors other than training and occupation. My own experience and the observation of the participants’ experience indicates that aptitude and psychological disposition can also considerably affect the speed at which the skill is developed. Skill development can be hindered by a bad experience, or conversely be triggered by a specific interest or need (Bleed, 2008). This shows how psychological factors may also play a role in the development of knowledge and that this may also be reflected in the final product.

It therefore becomes apparent that, in discussions on skill, precision is required about exactly which task, craft and context are concerned. Skill in vessel forming or other activities related to the broader craft of ceramics cannot be compared evenly with skill in figurine making. The forms of knowledge addressed are vastly different, and comparison leads to a redundant discussion. What must be assessed, before any comparison takes place, is the role of the people who made the figurines: were they ceramicists, apprentices or part-time figurine makers? This may of course not be possible archaeologically, but it must at least be closely pondered, as a safeguard for slippage into misrepresentative judgements. The situation at each peak sanctuary therefore requires close investigation before any comparisons, be they between figurines from different sites, different production units or different chronological periods can be undertaken. Ultimately, owing to the simple fact that the figurines were deposited at the peak sanctuary, it can be deduced that they were regarded as satisfactory and acceptable for use.

Finally, the notion of specialism must here be briefly discussed. It was first addressed in relation to peak sanctuary figurine production by Pilali-Papasteriou (1992, p.151) who remained sceptical about the existence of specialists owing to the fact that no specialised Bronze Age figurine workshops have been identified in Crete. Pilali-Papasteriou’s concern, however, can be alleviated with the argument that not all specialists have their own individual workspace. Especially in the case of ceramic production, it is common that differently trained and specialised workers share the same space (Costin, 1991). Thus, might early stage apprentices in the craft of ceramics and part-time participants who modelled and assembled the figurines be regarded as specialists in this task? While remaining entirely speculative, the suggestion is plausible. On the one hand, specialism does not necessarily equate with extensive craft knowledge (Forte, 2019). On the other hand, specialism can be temporary and shift in accordance with the stage of knowledge development (apprenticeship) one is at. Craft involves a long learning process in which many different stages of knowledge development are achieved.

Overall, in presenting a more complex–and thus more representative–image of the craft, this study reveals that it involved more subtleties than has been previously suggested. In demonstrating that there is more to the craft than meets the eye, it points to the limitations of correlating an object’s appearance with its maker’s abilities. A tight web of different intangible factors such as context, occupation, intention, psychological disposition, cognitive and motor skills, tradition and cultural or religious rules may have had an impact on the final form and appearance of a figurine.

Pursuing Research on Peak Sanctuary Figurine Manufacture

The research framework developed in this paper to tackle the question of who may have modelled and assembled small to medium-sized peak sanctuary figurines engendered a number of edifying suggestions on both how the craft may have been organised and on how skill can accordingly be discussed and assessed. In revisiting earlier and somewhat reductive views of the craft of figurine making, this study effectively proposes a more extensive, multi-faceted, socially-complex and culturally-embedded image of the activity. Consequently, I have raised more questions than I have conclusively answered, but in doing so, I have taken an important step in drawing attention to the depth, breadth and thus complexity of the topic under discussion. I may therefore propose a number of research routes worth investigating. One such route concerns the broader social networks existing around the artefacts’ production systems, namely in terms of communities of practice. What defined the latter? Were they confined to the workspace or might have they also encompassed other public spheres, private spheres and even certain parts of the landscape? Another worthwhile avenue of research consists in examining the relationships maintained between the potting and figurine making communities serving different peak sanctuaries. Were these communities in contact? How were the same modelling and assembling techniques noted on the figurines from different sites communicated and transmitted? Finally, the last investigative route proposed here concerns methodological matters. Is it possible to develop a scheme for identifying and recording skill on peak sanctuary figurines? While successfully and meaningfully engaging with these questions depends on the publication of, and access to, more archaeological material, contemplating their salience is in the meantime a valuable exercise.

Acknowledgements

The research forming the foundation of this paper was initially undertaken as part of my doctoral studies (2011-2016). I here wish to express my gratitude to Dr Evangelos Kyriakidis for granting me access to the Philioremos figurine collection, to Mr Vassilis Politakis for engaging in insightful discussions on craft practice, and to all the participants who joined in the experiments for their contributions and enthusiasm. I also wish to thank the anonymous reviews for their insightful and inspiring comments. This article was written during my position as Irish Research Council (Government of Ireland) 2019-2020 Postdoctoral Fellowship at Trinity College Dublin.

- 1Attributing specific dates to peak sanctuary figurines is a complex task given the poor preservation of most of the sites’ stratigraphy.

- 2Measuring up to 25cm in height for the anthropomorphic pieces and 15cm in length for the zoomorphic pieces.

- 3Measuring up to 8cm in height for the anthropomorphic pieces and 5cm in length for the zoomorphic pieces.

- 4Measuring up to 1m in height for the anthropomorphic pieces and 50cm in length for the zoomorphic pieces.

- 5The chronological system adhered to here is drawn from dates proposed in Momigliano 2007 and Shelmerdine 2008.

- 6Rutkowski’s 1991 catalogue of the Petsophas figurine material excavated by Myres in 1902, and Tzachili’s 2016 publication of the pottery and a portion of the figurines from Vrysinas are the most complete publications to date. They are extremely valuable contributions to the field.

- 7Owing to the currently unpublished nature of the collection, only a few of the original pieces are presented here. A full catalogue will be made available in the site report (Kyriakidis, in preparation).

- 8It is also conceivable that, for time saving purposes, several lower body parts were modelled in a row and left to harden, while a number of upper bodies were modelled in the meantime. By the time this task was completed, the lower bodies would be ready for joining to the upper bodies. The same applies to the female figurines. This notion is further discussed in Murphy, in preparation.

- 9The reconstructive replica samples were made with materials sourced in the vicinity of Philioremos, in line with the results of the fabric and petrographic analyses undertaken on the site’s ceramics. Transporting sufficient amounts of such materials from Crete to England, in order to successfully carry out the experiment with 60 participants, was however not possible. The malleability of the industrially-produced modelling clay employed instead was nevertheless very close to that of the Cretan clays.

- 10The figurine-making workshop was the second of three community-engagement events held over three weekends in July 2015, as part of the second Gonies Archaeological Ethnography Summer School.

- 11Pers. comm. Dr Christine Morris: an experimental workshop was held in May 2013 at Trinity College Dublin; less formally structured workshops, organised as part of university open days, were held in April 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016; and an exercise was organised in Crete, in July 2013, for students attending the Priniatikos-Pyrgos archaeological project.

- 12Although Myres (1902/3) and Rutkowski (1991) describe some of the figurines’ skirts as wheel-thrown, closer examinations of these pieces are required in order to establish precisely which techniques and devices were employed in their creation.

Keywords

Country

- Greece

Bibliography

Peak sanctuaries and Bronze Age Cretan figurines

Alexiou, S., 1967. Αρχαιότητες και Μνηµεία της Κεντρικής και Ανατολικής Κρήτης. Αρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον, 22, pp.384-385.

Berg, I., 2011. Exploring the chaîne opératoire of ceramics through x-radiography. In: S. Scarcella, ed. Archaeological ceramics: a review of current research. Oxford: BAR publishing. pp.57-63.

Davaras, C., 1982. Haghios Nikolaos Museum. Brief illustrated guide. Athens: Editions Hannibal.

Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki, N., 2005. The Archaeological Museum of Herakleion. Athens: EFG Eurobank Ergasias S.A. and John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation.

Gesell, G. and Saupe, T., 1997. Methods used in the construction of ceramic objects from the shrine of the Goddess with Up-raised Hands at Kavousi. In: R. Laffineur and P. Betancourt, eds. TEXNH. Craftsmen, craftswomen and craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 6th international conference, Philadelphia, 18-21 April 1996. Aegaeum 16. Liège: Annales d’Archéologie de l’Université de Liège. pp.123-26.

Karetsou, A., and Rethemiotakis. G., 1990. Κόφινας. Αρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον, 45(Β2), pp.429-30.

Kourou, N., and Karetsou, A., 1997. Terracotta wheelmade bull figurines from Central Crete. Types, fabrics, techniques and tradition. In: R. Laffineur and P. Betancourt, eds. TEXNH. Craftsmen, craftswomen and craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 6th international conference, Philadelphia, 18-21 April 1996. Aegaeum 16. Liège: Annales d’Archéologie de l’Université de Liège. pp.107-116.

Kyriakidis, E., (in preparation). The peak sanctuary of Philioremos. (sn. sl.).

Momigliano, N., 2007. Knossos Pottery Handbook: Neolithic and Bronze Age (Minoan). London: The British School at Athens.

Morris, C., 1993. Hands up for the individual! The role of attribution studies in Aegean prehistory. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 3(1), pp.41-66.

Morris, C., 2009. Configuring the individual: bodies of figurines in Minoan Crete. In: A.L. D’Agata and A. Van de Moortel, eds. Archaeologies of cult. Essays on ritual and cult in Crete in honor of Geraldine C. Gesell. Hesperia supplement 42. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies. pp.179-87.

Morris, C., 2017. Minoan and Mycenaean figurines. In: T. Insoll, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp.702-24.

Morris, C., O’Neill, B., and Peatfield, A., 2019. Thinking through our hands: making and understanding Minoan female anthropomorphic figurines from the peak sanctuary of Prinias, Crete. In: C. Souyoudzoglou-Haywood and A. O’ Sullivan, eds. Experimental archaeology: making, understanding, story-telling. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp.53-62.

Murphy, C., (in preparation). From making to breaking. An experiential study on peak sanctuary figurines. (sn. sl.)

Murphy, C., 2016. Reconciling materials, artefacts and images. An examination of the material transformations undergone by the Philioremos anthropomorphic figurines. PhD. University of Kent.

Murphy, C., 2018. Solid items made to break, or breakable items made to last? The case of Minoan peak sanctuary figurines. Les Carnets de l’AcoSt, (e-journal) 17, pp.1-10. https://doi.org/10.4000/acost.1089.

Murphy, C., 2019. Figurines as further indicators for the existence of a Minoan peak sanctuary network. In: (s.n.) Proceedings of the 12th Cretological congress. Irakleio: The Historical Museum of Crete.

Myres, J., 1902/3. The sanctuary site of Petsofa. Annual of the British School at Athens, 9, pp.356-87.

Peatfield, A., 1992. Rural ritual in Bronze Age Crete: the peak sanctuary at Atsipadhes. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2(1), pp.59-87.

Peatfield, A., and Morris C., 2012. Dynamic spirituality on Minoan peak sanctuaries. In: K. Roundtree, C. Morris and A. Peatfield, eds. 1992. Archaeology of spiritualities. New York: Springer. pp.227-45.

Pilali-Papasteriou, A., 1992. Μινωικά πήλινα ανθρωπόμορφα ειδώλια της συλλογής Μεταξά. Συμβολή στη μελέτη της Mεσομινωικής πηλοπλαστικής. Θεσσαλονίκη: Θεσσαλονίκη Εκδόσεις Βάνιας.

Platon, N., 1951. Το ιερόν Μαζά (Καλού Χωριού Πεδιάδος) και τα μινωικά ιερά κορυφής. Κρητικά Χρονικά, 5, pp.96-160.

Rethemiotakis, G., 1997. Minoan clay figures and figurines: manufacturing techniques. In: R. Laffineur and P. Betancourt, eds. TEXNH: craftsmen, craftswomen and craftsmanship in the Aegean bronze age. Proceedings of the 6th international Aegean conference, Philadelphia, 18-21 April 1996. Aegaeum 16. Liège: Annales d’Archéologie de l’Université de Liège. pp.117-21.

Rethemiotakis, G., 1998. Ανθρωπομορφική πηλοπλαστική στην Κρήτη από τη Nεοανακτορική έως την Yπομινωική περίοδο. Αθήνα: Βιβλιοθήκη της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας.

Rethemiotakis, G., 2001. Minoan clay figures and figurines: from the Neopalatial to the Subminoan period. Athens: The Archaeological Society at Athens Library.

Rutkowski, B., 1986. The cult places of the Aegean. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rutkowski, B., 1991. Petsophas: a Cretan peak sanctuary. Warsaw: Art and Archaeology.

Shelmerdine, C., 2008. The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spiliotopoulou, A., 2019. A discussion on the construction method of anthropomorphic clay figurines from the peak sanctuary of Kophinas and its correlations. In: sl. Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Cretan Studies. Heraklion: The Historical Museum of Crete. pp.1-11.

Sphakianakis, D., 2012. The Vrysinas ephebe: the lower torso of a clay figurine in contrapposto. In: E. Mantzourani and P. Betancourt, eds. Philistor: studies in honor of Costis Davaras. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press. pp.201-12.

Sphakianakis, D., (forthcoming). Η κύρα του Βρύσινα: σκιαγράφηση μιας ομάδας πήλινων ανθρωπομορφικών ειδωλίων από τη μινωική ακρώρεια του Ρεθύμνου. In: sl. ΑΕΛΛΟΠΟΣ: Tόμος Τιμητικός για την Καθηγήτρια Ίρις Τζαχίλη. np.

Tzachili, I., 2011. Βρύσινας Ι: Μινωικά εικαστικά τοπία: τα αγγεία με τις επίθετες πλαστικές μορφές από το ιερό κορυφής του Βρύσινα και η αναζήτηση του βάθους. Αθήνα: Βιβλιοθήκη της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας.

Tzachili, I., 2016. Βρύσινας IΙ: Η κεραμεική της aνασκαφής 1972-1973. Συμβολή στην ιστορία του ιερού κορυφής. Αθήνα: Βιβλιοθήκη της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας.

Zeimbeki, M., 1998. The typology, forms and functions of animal figures from Minoan peak sanctuaries with special reference to Juktas and Kophinas. PhD. University of Bristol.

Zeimbeki, M., 2004. The organisation of votive production and distribution in the peak sanctuaries of state society Crete: a perspective offered by the Juktas clay animal figures. In: G. Cadogan, E. Hatzaki and A. Vasilakis, eds. Knossos: Palace, City, State. London: The British School at Athens. pp.351-61.

Crafts, knowledge, skill, learning and apprenticeship

Arnold, D., 1985. Ceramic theory and cultural process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bleed, P., 2008. Skill matters. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15(1), pp.154-166.