The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Let’s Build a Medieval Tile Kiln - Introducing Experimental Archaeology into the University Curriculum

As a lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) I teach a course on medieval archaeology and run a successful programme in designing exhibitions for local museums and community groups. I also encourage my students to take part in the community archaeology and history projects that I run with archaeological and historical local groups in Preston. Students are very keen to take practical work, whether it is researching, excavating, designing a website or conducting local oral history projects, and they gain a lot of confidence from these experiences.

This article describes reconstructing and firing a 14th century floor tile kin in the grounds of the museum where the original was found. The author discusses the use of the innovative Problem Based Learning pedagogy to inspire the students and asks if is possible to bring experimental archaeology projects into the University curriculum.

I wanted to see if it was practical to develop an experimental archaeology programme within a BSC Archaeology degree course, but there were some issues such as resources and time limits that need to be considered before I could start to design a formal program. I have been interested in experimental archaeology since I saw research undertaken at a local museum in Cheshire, and I thought a similar experiment to that would be a good student project. Crucially it would also have scientific merit; this was a ‘real’ experiment with a research question developed by the students. After discussions with Norton Priory Museum (www.nortonpriory.org), it was agreed that I could reconstruct and then fire a medieval floor tile kiln on their grounds.

NortonPriory Museumhas already been the subject of extremely through excavations throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In 1972 the lower structure of a fourteenth century tile kiln had been found in the monastic complex (Greene 1989). Built of cob (a mixture of local, red clay, sand and straw), pebbles and tile wasters, the kiln was of a solid construction and so well preserved that it was possible to move it for display in the museum.

The museum has also been the site of experimental projects run by archaeologists working there. During the 1978 - 1979 excavation seasons, Greene and Johnson (1978) conducted two successful firings of a reconstructed kiln, examining the design of the kiln and the stacking techniques that might have been employed by the craftsmen.

Repeating these experiments, focusing again on the design and the possible of elimination of ‘cold spots’ was interesting so I recruited, via social media and posters, two very diverse student groups, archaeology students and also ceramics students, who were willing to use their spare weekends and two weeks in the summer vacation learning about kilns and cob making.

As I thought about the potential of students as self directed learners engaged on a problem that was challenging and motivating, I decided on two loosely defined learning objectives that students should, after the conclusion of the project and through a process of self reflection, be able to achieve:

- Students should demonstrate confidence in their own abilities as researchers, as they would be involved with all aspects of the experiment from the design of the kiln, and possible publication of their research in UCLAN’s student journal, Diffusion.

- Students should be able to recognise the generic and subject specific employability skills that they had developed (perhaps through their Curriculum Vitae and any subsequent careers planning).

Through my reading about pedagogic techniques, I have become very interested in the Problem Based Learning (PBL). This has been defined as “the learning that results from the process of working towards the understanding of a resolution of a problem. The problem is encountered first in the learning process” (Barrows and Tamblyn 1980, 1).

Within a PBL teaching session the lecturer presents the students with a stimulating problem or scenario, which the students then attempt to resolve, developing their own lines of research and using their existing skills and knowledge.

As outlined by Barrett and Cashman (2010, 8) a PBL approach is characterised by:

- a presented problem that is deliberately loosely structured, incomplete and challenging;

- a team based approach, requiring students to work in small groups, supporting each in their learning, defining what they do not know and what they need to discover;

- assessments aligned with learning objectives;

- a change in the traditional role of the lecturer: becoming a resource, learning by working with their students, asking questions and encouraging students to be responsible for this own learning.

PBL is a very challenging way to teach, precisely because it empowers the student to take control of what and how they want to learn. A successful PBL project can motivate students to develop their key generic skills in team working, communication, critical analysis, problem solving, et cetera.

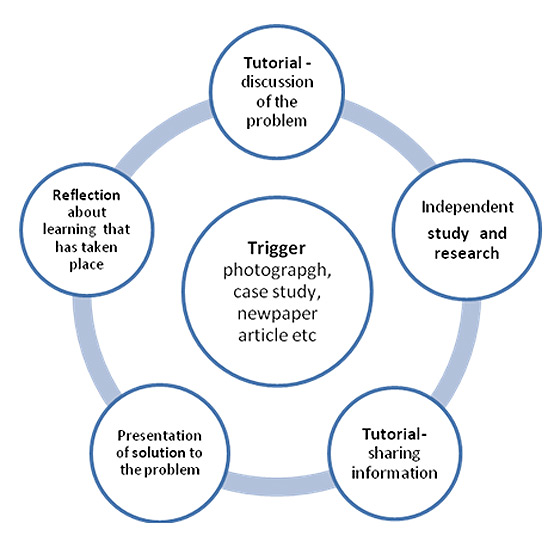

Fig 1. The PBL learning cycle

To start a PBL project, the project has a ‘trigger’, for example: a photograph, a document, or a case study as a starting point. I chose a photograph of the excavated kiln and then a visit to the museum to actually look at the kiln.

The students decided the research question for the team would be to try and design a roofless structure that would function efficiently up to one thousand degree centigrade and eliminate ‘cold spots’ in the firing process. Cold spots are areas within the kiln where the hot gases do not circulate efficiently and the pottery will not fire correctly. These areas can be due to the design, stacking of wares or incorrect firing techniques. This meant a considerable amount of research from the students as we discussed the project and looked at what we needed to know about the design of medieval kilns.

In 2009 we actually fired the kiln with around 200 handmade, clay floor tiles in it. It burned for 24 hours and consumed nearly three tonnes of wood. We learned that a cob structure will, if fired correctly, easily maintain temperatures of up to one thousand degree centigrade and the structure will survive in good condition.

We discovered that our design, slightly different to that of the 1978 version, was easy to stack because it was not roofed and was covered only with a light layer of broken tiles placed directly onto the tiles that would be fired. We did not have to demolish part of the structure to retrieve the tiles, so any damage to the kiln was unnecessary. This could expand the life of the structure for repeated firings, necessary if producing the huge volume of tiles that the monastic complex would need.

However, we were less lucky with our design of the kiln floor, which had to support the weight of tiles in the firing. We had used tree branches coated in cob, bent in arches above the fire and then cobbed into the walls, rather than tiled arches of 1978 experiments (Greene and Johnson 1978). Ours were partially successful but difficult to maintain and replace after one firing. Next time we would have to develop the skills to build those stronger arches made out of old waster tiles.

The students’ design did not eliminate ‘cold spots’ within the kiln, and we had one corner of the structure where the tiles were poorly fired. This could be due to the poor design of the kiln floor, which failed to allow the hot gasses to circulate, or to the uneven nature of the kiln floor, which meant that the tiles were not stacked efficiently and so impeded the hot air flow.

The students were delighted that the design had worked, regardless of these issues. We had been concerned that the kiln might blow up before it hit temperature because we were building it purely from cob. In a conversation on the 6 June 2009 with John Hudson, an experimental potter and member of the Medieval Pottery Research Group, he stated that this is the first cob kiln he has ever seen fired.

Afterwards I asked the students to reflect on their experiences and what they thought that they had learned during the many hours we had spent on this experiment. All agreed that it had pushed and challenged them and that they had used existing skills and developed other such as project management and critical thinking. The ceramists, with their more specialised skills, especially valued the chance to fire a wood fuelled kiln, something that they had not had the opportunity to develop throughout the three years of their degree course. One student was determined to publish her research into kilns in the student journal at UCLAN and later did so (Tyrer 2009).

The most interesting quote was from a ceramics student in her personal reflection (Anon. 2009), which rather summed up what I had hoped to achieve. She wrote: “Surely academe is about pushing yourself and attempting to further knowledge and experience, and also to share this journey with others? If we don’t push more, try more, strive more, we might as well be stacking shelves in Tesco's.”

This was an extremely difficult project, far harder and more ambitious that I had first thought, but I felt that the PBL technique had worked really well and that it gave both the instructor and the instructed much to reflect on.

On reflection I felt that I had learned that I had to allow the students the space to develop their research ideas and their design for the kiln. There was a possibility that they could fail to produce a workable design, but as long as no-one was injured in the firing process, I felt that was a risk worth taking.

Another key strategy I discovered was to encourage co-operative working, with students discussing and critiquing their own ideas, sharing their research and not concentrating on what they thought I wanted. It is best to offer advice or further suggestions when asked, but there is a need to step outside the traditional role of the lecturer who has all the answers. Team working is very powerful tool to motivate and engage students; they can take ownership of a project and develop it.

Importantly, I learned that asking for the impossible really can work and that often we do not challenge our students enough. We need to allow students a safe environment to be creative and confident in (and perhaps in which to fail) as there are valuable lessons to be learned there as well.

I would not repeat an experiment of this size again because it was expensive and hugely time consuming. Rather, I would develop other research projects and base them on more specific experimental archaeology questions. I think that there is a place for experimental archaeology within the university curriculum and that PBL is an interesting way in which to teach it. Of course, this experiment had its short comings and any other PBL experiment would need to be properly designed for the curriculum and have stronger methods of evaluation.

If, after reading this short article, you are inspired to research an archaeological problem working with your students, and developed this through the PBL pedagogy, I (and my students) would be delighted.

Keywords

Country

- United Kingdom

Bibliography

Anon. 2009. Personal refection on the kiln project [reflective diary] ( personal communication 30 August 2009 ).

BARRETT, T., CASHMAN, D. (eds.) (2010) A Practitioners’ Guide to Enquiry and Problem-based Learning. Dublin: UCD Teaching and Learning.

BARROWS, H.S. & TAMBLYN, R. (1980) Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education. New York, Springer.

BROWN, F. And HOWARD- DAVIS, C. 2008. Norton Priory: Monastery to Museum Excavations 1970 – 87. Oxford. Oxbow.

GREENE, J.P. 1989. Norton Priory. The Archaeology of a Medieval Religious House. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press

GREENE, J.P and JOHNSON, B. 1978. ‘An Experimental Tile Kiln at Norton Priory, Cheshire’, Medieval Ceramics 2, p. 30-42.

HUDSON, J. 2009. Discussing the design of the kiln. [conversation]. ( personal communication 6 June 2009).

TYRER. S, 2009. The Norton Priory Medieval Tile Kiln Project. Diffusion 1 (2) p.10 -15. [Online]. Available: http://www.uclan.ac.uk/information/services/ldu/research/norton_priory_medieval_tile_kiln_project.php, [Accessed 9 March 2013].