The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

From Celtic Village to Iron Age Farmstead: Lessons Learnt from Twenty Years of Building, Maintaining and Presenting Iron Age Roundhouses at St Fagans National History Museum

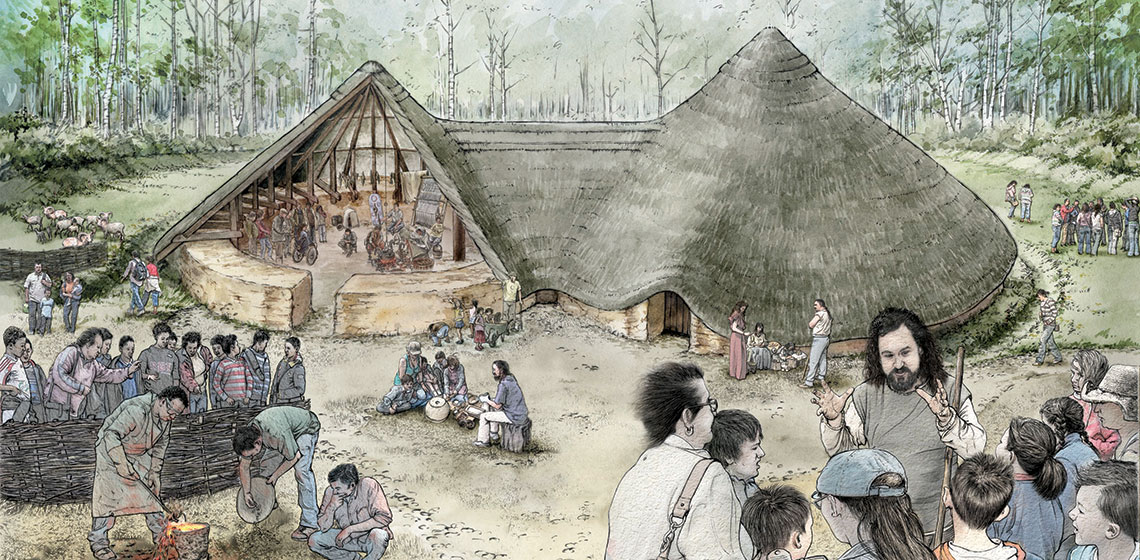

This article summarises the main issues that were faced in running a group of reconstructed Iron Age roundhouses as an educational and visitor resource at St Fagans National History Museum from 1992 until 2013. Plans to build a new Iron Age farmstead at St Fagans are then outlined along with the steps that will be taken to learn from past experience and further improve the quality of the visitor experience in future.

Introduction

In February 2013 St Fagans National History Museum closed its Celtic Village after over twenty years of continual use as a popular visitor attraction. This pioneering development was built for the museum by Peter Reynolds of Butser fame and consisted of three Iron Age roundhouses set within a palisaded enclosure. From the outset its remit was primarily educational, providing a resource for schools which were teaching the Iron Age Celts component of the Welsh National Curriculum, although several experiments were conducted within its environs over the course of its life. Most notable of these were the excavation of the original Moel y Gaer house by Professor Martin Bell, Reading University (2009), the excavation of the Moel y Gerddi house by Dr Oliver Davies, Cardiff University, and the present author (2012), and smelting and brazing experiments by Tim Young, Cardiff University (1998 - 2004).

The three houses that made up the Village were based on excavated evidence from Moel y Gaer in northeast Wales (Guilbert 1976; 1982), Moel y Gerddi in northwest Wales (Kelly 1988) and Conderton in the English Borders (Thomas 2005), with the palisade being a construct designed to provide physical coherency to the Village rather than reflecting a specific site.

St Fagans is best known for the display of ‘real’ buildings, moved and re-erected stone-by-stone and brick-by-brink, a service it has performed for over 60 years. The Celtic Village was therefore something of a departure being based, as it was, on archaeological evidence and engineering principles and being built using wood, stone and straw bought for the purpose rather than derived from an original building. Nonetheless, over its twenty-year life span it proved enormously popular with visitors and was the setting for many re-enactment and craft events. Indeed, at the time of its closure, it was welcoming 13,000 school children and perhaps as many as 250,000 visitors throughout the 361 days each year that St Fagans is open (See Figure 1).

As with all reconstructed roundhouses, the structures at St Fagans were all repaired and altered over the course of their history. The thatch on all of the houses had to be patched after just eight years. At the same time, the roof structure of the Conderton house had to be reworked since the original design allowed water into the stone walls. Nine years later, the Moel y Gaer house had to be taken down due to structural failure being completely rebuilt the following year following excavation by Professor Martin Bell of Reading University. The Moel y Gerddi house lasted three years longer but was finally closed to the public for safety reasons in 2012.

In summary, as the houses grew older the resources needed to maintain them increased and eventually exceeded what was available, hence the decision to close the Village to take stock of what we had learnt from the previous twenty years and to plan for a new series of Iron Age structures. This article details the results of these reflections and outlines our plans for the redevelopment of the Iron Age roundhouses at St Fagans.

Lessons from the Celtic Village: water run-off and ventilation

One of the dominant themes that runs through the maintenance records for the Celtic Village is the consequence of its build location, set as it was at towards the base of a hill, surrounded by tall trees. This meant that the site was plagued by water run-off from the hill, and also failed to benefit from drying breezes, resulting in very damp conditions. Several attempts had been made to mitigate these problems over the years. The ditch of the palisade was intended to catch the run-off with drainage pipes beneath the houses carrying water away but, over time, the ditch filled-in and the pipes clogged.

The choice of hillside location had one additional consequence for water ingress in the Celtic Village. In order to produce flat ground upon which to build, Peter Reynolds followed a practice common in prehistory and cut a level platform into the hillside which extended about 30 cm beyond the south wall of the Moel y Gerddi house with the palisade bank rising beyond this. Over the years the vertical edge of this platform eroded and soil washed down slope until it butted against the outer wall of the house, leaving its floor effectively underground by some 30 cm. Attempts were made to cut back the hill wash in the early years of the Village but, over the course of its life span, the extent of the original platform was forgotten and efforts to cut it back ceased. As well as putting pressure on the wall of the Moel y Gerddi house, this meant that the internal environment was cold and damp resulting in more rapid deterioration of the house contents. Presumably many Iron Age roundhouses built onto hillsides would have encountered similar problems if the edges of their platforms were not set far enough back, or if any resulting hill wash was not routinely cut back (See Figures 2 and 3).

The woodland location provided the final dimension to the water-based problems faced at the Celtic Village. The shading of the site by trees further exacerbated the problem of damp since it meant that the thatch didn't dry out, causing it to rot at a faster rate than anticipated and leading to greatly increased maintenance costs, as noted above. The lighting of fires within the house, helped to dry the thatch a little, but the fires were allowed to die back when the museum was closed. The effect of this heating regime on the environment within the Moel y Gerddi house were recorded in its last years using TinyTag Dataloggers to monitor heat and humidity both inside and outside, supported by a thermocouple placed within the central fire. These devices allowed the relationship between the fire, the internal environment and the ambient conditions to be monitored and analysed. This programme indicated that the house had returned to an ambient temperature by the early hours of the morning. Further experimental work using a thermal imaging camera showed that the fire regime inside the Moel y Gerddi house did elevate the temperature of the thatch, but one only had to push one's hand into the roof to determine that it was not sufficient to dry the sodden straw (See Figure 4. Thermal images recorded at regular intervals before and after the lighting of a fire in Moel y Gerddi in 2013. It can be seen that the temperature of the thatch's outer surface rose very quickly before dropping away after about 30 minutes. The reason for this is not entirely clear, but it is possibly a result of water evaporating from the surface before the thatch temperature reaches an equilibrium.).

The conclusion reached from our attempts to control water flow, damp and humidity levels in the Celtic Village is an obvious one: that the choice of location is critical to the long-term integrity of the structure and the environment of its interior. It is rare that archaeological open-air museums have a completely free-hand in the choice of location for their buildings, but our own experience indicates the importance of considering these factors.

Lessons from the Celtic Village: disabled access and light levels

The location of the Celtic Village brought another set of difficulties, this time for our visitors rather than for the buildings themselves. Access to the site was along a steep and uneven path which was an obstacle to wheelchair users. Furthermore, the entrance to the Moel y Gerddi house involved stepping over a low-wooden sill - even though there was no archaeological evidence for such a feature at the original site—presenting another obstacle for people with mobility impairments. Once inside light levels were very low which made it hard for people with vision impairments, or indeed for anyone, to see the house's contents or to navigate the house (See Figure 5).

Disabled access issues are not unique to the Moel y Gerddi house and can be found at many open-air museums which seek to present historic buildings as they once were. But, the approach to such issues has changed over the twenty years since the Celtic Village was built, and there is now far greater awareness of the needs to provide equality of access wherever possible, both at an ethical but also a legal level. The UK's Equality Act 2010 protects people from discrimination in the workplace and wider society. It requires service providers, of which museums are an example, to make reasonable adjustments in order to ensure they are accessible to all. In the present context this could involve changing the physical features of a site to allow access, or providing additional services. If an individual feels that reasonable adjustments have not been made to allow them to access the site then they can make a claim under the act, the validity of which will be decided in court. An access assessment undertaken at St Fagans in 2011 highlighted the extent of the problems for disabled visitors to the Celtic Village and made it an imperative that we resolve as many of these issues as possible so that all of our visitors could enjoy a taste of Iron Age life.

Lessons from the Celtic Village: coping with success

Perhaps the greatest single factor affecting the visitor experience in the Celtic Village was simply the sheer success of the structures. Visitor numbers have already been quoted and on a peak summer day it was possible for 6-7,000 people to visit the Village as part of their trip to St Fagans. This placed great demands on the individual buildings. Both Moel y Gaer and Conderton only had single low doors and had maximum occupancy levels for fire regulations of 12 people each, Moel y Gerddi had two opposing doorways and was rated for 35 people. On a busy day, the doorways were often log-jammed with visitors attempting to get in and out, while simultaneously blocking the light for those already inside. Staffing levels in the Village exacerbated the problem.

When it was first built the Celtic Village was only open to the public for six months of the year and it was staffed by two people equivalent to a single annual salary. This model allowed one person to speak to the public, while the other looked after the Village; however, after a few years, demand for access to the Village reached such a level that the decision was made to open it all year round. At this point the staffing model had to change; employing two people for the whole year rather than for half of it would have doubled the running costs for the Village and there are many other buildings at St Fagans which need to be staffed. The post of Celtic Village facilitator therefore became a single full-time position. The quality of experience offered by the individuals who occupied this post over the years is well-documented in visitor feedback, but the sheer volume of visitors coming to the Village meant that they couldn't provide the same high quality experience to everyone. Furthermore, it was only possible for them to occupy a single house at a time, particularly on busy days, and the other two houses were therefore left unmanned. For safety reasons, no fires could be lit in these unmanned houses, and their contents had to be removed to prevent damage or theft. They were sad and empty structures which offered little to visitors and were a constant frustration to staff.

Beyond the Celtic Village

The closure of the Celtic Village provided an important opportunity to reflect on these varied issues. Fortunately, concurrent with the decision to close, came the decision to build a new Iron Age experience at St Fagans, thereby providing an opportunity to turn reflection into an improved visitor experience. Site location, water management, visitor flow, building design and staffing all became variables which could be altered. At the time of writing we are about half way through the building of our new Iron Age reconstructions and so what follows in this article is an overview of a work-in-progress, complete with our current thoughts on solutions to specific design problems. It is possible that these will alter as the reconstruction continues.

Beyond the Celtic Village: location

In developing our plans for the new buildings the first issue we addressed was their location taking the opportunity to build on a new site at the top of a hill where the woodland is thinner and the available clearing larger. This position will, we hope, be less affected by water run-off and will benefit more from a drying wind.

The chosen location is set further away from the main visitor routes at St Fagans than the old Celtic Village, a point which has both positive and negative sides. On the one hand, it is likely that the new Iron Age structures will receive fewer visitors than did the Celtic Village, although the number of school groups on visits linked directly to the History Curriculum is unlikely to change. On the other hand, the number of visitors is likely to be more in keeping with the scale of the structures, thereby allowing us to provide a better visitor experience for those who do make their way up the hill.

Beyond the Celtic Village: the basis of the reconstruction

The second issue we faced was what we should build. In 1992, Iron Age roundhouse reconstructions were relatively rare. Today there are over 126 roundhouses in Britain and Ireland (British Roundhouses 2015). The majority of these are based, to a greater or lesser extent, on the work of Peter Reynolds who provided an architectural template for wattle-walled roundhouses and also explored the design of stone-walled roundhouses. One form he did not attempt to reconstruct was the earth-walled roundhouse. In recent years there has been a growing recognition that in western Britain roundhouses were often built with thick earth walls, sometimes with a stone cladding, and sometimes with internal rings of posts: see Bryn Eryr, Anglesey, (Longley 1998); Cefn Du, Anglesey, (Cuttler et al 2012); Poldowrian, Cornwall, (Smith and Harris 1982). Since Wales has provided several examples of this type it seemed particularly appropriate that St Fagans National History Museum should attempt a reconstruction.

It was decided to base our reconstruction on evidence from Bryn Eryr, an Iron Age farmstead on Anglesey, an Island off the north coast of Wales. In its second phase, Bryn Eryr consisted of two clay-walled roundhouses built abutting one another with conjoined drainage gullies around their circumference suggesting they were in use contemporaneously. Each house had a doorway opening to the east, and looking out onto a cobbled yard, while behind were drainage ditches and clay quarry pits. The houses were set within a large rectangular enclosure which, due to pressures of space, it will not be possible to build at St Fagans (See Figure 6).

A number of different design possibilities exist for clay-walled roundhouses, with the wall height being a crucial variable. Peter Reynolds noted that wall height was a particularly problematic area in some of his own reconstructions. In his publication of the Pimperne reconstruction he noted that, in the absence of archaeological evidence or structural necessity, this was the only variable that he decided arbitrarily (Harding et al 1993, 95), the decision being to build the walls to 1.52 m in order to allow headroom when stood close to them.

In part the ability to build to any height depends on the strength of the raw material. If roundhouses were built with pure clay then the wall height would, of necessity, have been low, corresponding to the natural angle of repose of the clay when dry. Given that this angle of repose is around 30 degrees, the 1.7 m thick walls at Bryn Eryr could only have been raised to around 0.5m high before they became unstable, but this need not have been the case, as the strength of clay can be significantly increased by mixing it with coarse aggregates, straw and stone dust to make a building material known as clom in Wales (cob in England). This material can be very strong, allowing walls of around 0.6m thick to be raised to over 2.4 m tall, as evidenced by the clom-built Nantwallter house at St Fagans which was built around 1770, and moved to the museum in 1990 (See Figure 7).

No detailed description of the composition of the material used to make the walls at Bryn Eryr could be found in the excavation archive. Consideration was given to the possibility of returning to re-excavate the site in pursuit of this information, but the excavation report is clear that only the lower few centimetres of the walls survived at this time, making it unlikely that significant material would survive to the present. Nonetheless, the excavation archive makes clear that the area is rich in clays and well-supplied with coarse and fine aggregates - the raw materials of clom buildings. It was therefore decided to build our roundhouses with walls around 1.5 m high. This is an arbitrary measurement - as any other choice of height would have been—but it has the advantage of maximising headroom, and usable floor space, within our buildings. The clay for our houses was procured from Pembrokeshire whereas that used at Bryn Eryr could easily have been provided from the immediate environs of the site. Sufficient could have been obtained from the excavation of the enclosure ditch which surrounded the original site, with the quarry pits set within the interior of the enclosure potentially supplying patching material for ongoing maintenance (See Figure 8).

The method by which two prehistoric houses could be built abutting one another, as was the case at Bryn Eryr, was particularly vexing, although it is known from other sites such as Tre'r Ceiri, a hillfort in Gwynedd, north Wales and Chysauster in Cornwall. Reconstruction drawings of both sites show the roofs of the roundhouses as separate cones, which touch where their walls butt (for example People’s Collection Wales 2010 and Cunliffe 1995, pl 6). Such a design would lead to water run-off from the roofs meeting at the join between the two buildings, leading to water penetration into the walls, and subsequent erosion. To reduce the risk of this occurring at our houses, we decided to join our two roundhouse roof cones using a linking ridge, thereby pushing the water away from the tops of the walls. One consequence of this design is that a disproportionate amount of water would be funnelled from the roofs to the ground where the two houses join—potentially creating a waterlogged patch of ground. Referring back to the archaeological evidence from Bryn Eryr, a large drainage gully had been dug behind the buildings, from the point where their walls joined, thereby channelling water away. No such drainage ditch existed at the front of the buildings, but one possible solution to the problem of excess water flow is to place a water barrel below the eaves, thereby obviating a drainage problem and providing a ready supply of water for the inhabitants of the houses.

The solution we have chosen for the problem of how to combine two roundhouse roofs means that our structures will inevitably look different from single-roofed roundhouses of the types explored by Peter Reynolds and we hope that this will generate debate. Pragmatically however, the inclusion of a linking ridge between the two houses provides us with the solution to another issue faced in the old Celtic Village—namely accessibility.

Beyond the Celtic Village: accessibility and light levels

Fire safety makes it necessary to include more than one exit from large buildings, regardless of their presence in the original structure. In the case of our new roundhouses, it was decided not to alter the external appearance of the houses, but to include a doorway linking the two buildings which would run beneath the joining roof ridge, thereby making it possible for visitors to enter via one house, pass into the second house, and leave from the second doorway. This will reduce congestion at each doorway, improve visitor flow through the houses, and make it easier for staff to supervise both structures. In quieter periods, the linking doorway will be concealed behind period-appropriate fabric drapes.

The issue of disabled access into the roundhouses is also helped by the evidence from the original site of Bryn Eryr. The doorways of the original houses were already wide enough for wheelchairs and there is no evidence for sill beams, meaning that the buildings are, by their nature, easier to enter than were Moel y Gerddi and Moel y Gaer in the old Celtic Village.

Lighting has been a particular concern in the building of the new Iron Age farmstead since the thick clay walls at Bryn Eryr will reduce the spread of light entering through the doorways. Since the reconstruction is still only partly complete, it is not certain how problematic this will be, but it is an area that has been explored with the support of the Cardiff School of Architecture. In 2012 a scale model of the Iron Age farmstead was produced and tested within the Cardiff School's Artificial Sky Facility to gain a sense of how much light would enter the interior, and whether any minor alterations could be made to the design to improve light levels inside. The conclusion of this leads us to believe that the light levels inside the houses will indeed be very low (See Figure 9).

Many options were considered for increasing the light level into the houses, from dormer windows in the thatch to windows in the wall and several of these were tested in the model. All were felt to be too intrusive and—while they did not exactly contradict the limited evidence base—they suggested more than the evidence from other sites could support. For this reason, it was decided to focus attention on the naturally available sources of light: the doorways, the gaps under the eaves, and the fires within the buildings. These will be the main sources of light available to visitor once inside the roundhouses, however, they will not provide adequate light to all parts of the houses, and will be insufficient for visitors with sight impairments. Therefore, the houses will also be equipped with concealed electric lighting behind the wall plate, thereby enhancing the light levels provided by the gaps in the eaves while preventing visitors from seeing the light source. The facilitator will therefore have the option to raise or lower the light levels in the houses according to the needs of visitors.

Beyond the Celtic Village: experiment or experience?

So far, this article has focused on the practical issues affecting the development of the Iron Age farmstead, not least because this is an area that is little explored in most articles which deal with roundhouse reconstructions. Indeed, the practicalities involved in catering for visitors are sometimes presented as a negative, leading as they do to deviation from an archaeological ideal (Harding 2009). I hope therefore that the discussion above has helped to illustrate why such compromises are made, particularly at venues which receive a high volume of visitors. A roundhouse which can't be opened for reasons of fire safety, can't be entered because of poor access routes, and can't be seen because the interior is too dark will not teach many visitors about the Iron Age; whereas the compromises we have made are all ones which can be explained to the public while they are sat enjoying the ambience inside the houses.

This raises the question of what we are reconstructing at St Fagans. Is it Bryn Eryr itself? Clearly not, given the compromises noted above, and the availability of other solutions to the design problems posed by the archaeological evidence. In an ideal world we would therefore present our roundhouses to the public as an "Iron Age farmstead, based on Bryn Eryr, Anglesey" rather than simply "Bryn Eryr". However the name of the structures proved to be a very contentious point among staff at St Fagans. Almost all of the buildings in the museum are known by a site name, for example "Nantwallter cottage", "Llainfadyn cottage", "Cilewent farmhouse", and it was felt that to deviate from this pattern would be to devalue the work of the many who were involved in the building work – their hands had been engaged in the building of a specific space, not a theoretical construct. For this reason, our Iron Age roundhouses are known to all as “Bryn Eryr” with the discussion of the archaeological basis being part of the responsibility of those who interpret the building for the public.

A further question exists as to how much these structures can be regarded as experimental. From the outset, Peter Reynolds distinguished the educational structures that made up the old Celtic Village from the experimental structures which he maintained at Butser, observing the impossibility of running one structure for both ends. The new Iron Age farmstead is also decisively an educational resource. The roundhouses explore themes not previously addressed on a large scale—such as clay-walled building—but they have not been designed explicitly as an experiment in a strictly scientific sense. Instead, we hope that they will become a venue and a backdrop for experiments, thereby helping the public to understand how archaeological knowledge is obtained, while also encouraging the skills with which visitors can critique the reconstructed buildings themselves.

The success of the Iron Age farmstead as a teaching resource, both for schools and the general public, will depend to a great extent on the richness of the narrative that is generated around each aspect of the site. The grounding of the site in the archaeology of Bryn Eryr provides one example of this, allowing staff to introduce a specific Iron Age site and explain how it has influenced our design. The story of the clay walls is another example, introducing visitors to a building technique which is now unfamiliar but was once widespread. Even light levels and water flow will be the subject of discussion with visitors, encouraging conversations which will, no doubt, range across modern issues of sustainability and accessibility as often as they do through life in the Iron Age past. Two additional areas in which we have invested considerable efforts to deepen the narrative of the site are; the thatching of the roofs and the fit-out of the interior (both ongoing at the time of writing).

Beyond the Celtic Village: thatching the roofs

The materials and methods used to thatch roundhouses in the Iron Age is a subject which has not received a great deal of attention when compared to the literature available on the nature of walls and roof timbers. This is perhaps not surprising given that, in many cases, the form of roundhouse walls can be extrapolated from archaeological evidence, and roof structures can be approximated using engineering principles, whereas these two sources of information rarely offer guidance as to the choice of roof covering. As a result several roundhouses—including examples in the old Celtic Village—have been roofed with triticale which is a 19th-century hybrid of wheat and rye and was not available in the Iron Age.

In building the new Iron Age farmstead, we wanted the thatching material and method to be a key part of the interpretation. Looking back at the original evidence from Bryn Eryr it is clear that the owners of the original site grew, or had access to, spelt, as grain was found during wet sieving of archaeobotanical samples. Working with the advice and support of John Letts, an expert in historic thatch, it was determined that spelt grew tall enough to have been used as a thatching material unlike many modern varieties of wheat which have short stems that reduce the chance of them being damaged by high winds and poor weather.

An estimate was made of the surface area of the roofs in the Iron Age farmstead and this was converted into a volume of crop and the area needed to grow that crop: 3.5 hectares. St Fagans is fortunate in having access to extensive farmland around the perimeter of the museum, so it was decided to plant enough spelt to thatch the houses.

This project involved many uncertainties. Would spelt seed grow well in the soils at St Fagans? Would the crop survive the predation of rabbits, storm damage, weed infestation and disease? Would the museum have the technical know-how to grow a crop of sufficient quality for thatching? Would the museum have the resources to harvest such a large volume of material? This latter point was a critical one. The commitment to grow sufficient spelt to thatch two houses meant that it would not be possible to undertake the work using labour-intensive Iron Age methods. For this reason, modern equipment was used throughout, but not modern fertilisers or pesticides.

Modern machinery meant that ploughing the field and planting the crop was a relatively quick and labour-efficient operation, undertaken in late autumn. Harvest in mid-summer was a different matter. In order to ensure that the straw was preserved as lengths, it was necessary to harvest using an early-20th century reaper-binder - a less labour-intensive method than harvesting with a sickle, but much more intensive than using a combine harvester (See Figure 10).

Teams of people were assembled to the task of following the reaper-binder, collecting the bound sheaves and setting them upright to dry. Ideally, the sheaves would have been threshed to remove the heads while still in the field, but impending poor weather meant this wasn’t possible, and they were moved to storage in barns around the museum. From these locations a range of threshing methods were tried in order to remove the grain from the straw. Initial attempts were made with flails and heckles, neither were appropriate for the volume of material and the limited pool of labour available to the museum. More productive was the laying of lines of sheaves along the path followed by the museum's land train (used by visitors to cross the site). The land train's wheels crushed the grain from the straw in imitation of the role that cattle's hooves may once have served. However, even this was too labour intensive and slow to fit with 21st-century needs. In consequence the decision was made to thresh the remaining crop using an early-20th century threshing machine which massively increased the work rate (See Figure 11).

Few lessons relevant to our understanding of prehistoric life can be learnt directly from this experience, but the conclusion for those of us who were involved in it was that many previous narratives of Iron Age life have underestimated the significance of the harvest in the annual rhythm. However the harvest was managed, the inhabitants of Bryn Eryr will have found their late summer and early autumn dominated by the gathering and processing of the crop, as did we. It is a task which must have involved many people - probably drawing on a population from beyond the farmstead itself - and which would have consumed the attention of the community. There were few short cuts in a process which involved moving and processing tonnes of material. Indeed it was a task which probably took much more effort than the cutting and preparing of timbers for the roof.

Thatching is still in progress in our Iron Age farmstead, but it will also reflect a different view of how Iron Age roofs were covered. In the past roundhouse roofs at St Fagans have been thatched using a combed wheat style. This technique produces very neat roofs and reflects the availability of high quality straw, processed using a reed comber to ensure the stems remain uncrushed; it is a technique which requires the use of machinery during the processing, and considerable expertise during the thatching. John Letts, who has advised us through the thatching project, has recommended an alternative technique, stuff thatching, since it better reflects the damaged quality of the hand threshed spelt straw likely to have been available in the Iron Age.

Using this technique the roof is built up from a base coat, in our case of heather and gorse, with the spelt then being stuffed into this base, forming a durable top coat. Patching the roof should be easier in future because sections of the stuff thatch can be replaced as needed. Furthermore, the process is relatively low-skilled meaning that it can be executed with the support of volunteers. Naturally, it waits to be seen how durable the stuff thatched roofs will be and how they will perform in relation to the waterlogged roofs of the old Celtic Village, but our experience will hopefully act as a spur for further consideration of the thatching techniques which may have been used in prehistory. In the meantime, the net result of our efforts is that the roofs at the Iron Age farmstead are as much a part of the narrative of the buildings as the walls and timbers, and are not just an expedient means of keeping the buildings dry (See Figure 12).

Beyond the Celtic Village: fitting out the interior

Throughout its active life, the Iron Age farmstead will have to serve two distinct audiences: the school groups undertaking structured curriculum-based studies, and the general public whose learning is self-guided. The two conjoined roundhouses will help us to serve the needs of both of these audiences in a way which was not possible in the old Celtic Village. The smaller roundhouse will be presented as a model of Iron Age life, illustrating the range of activities that are likely to have occurred: for example, food preparation, eating, craft work, socialising and sleeping. The larger roundhouse is capable of seating 30 school children and will serve as a classroom, more geared to activity than to the presentation of contents.

In commissioning the contents for the smaller roundhouse, St Fagans is fortunate in being part of the same overarching organisation as National Museum Cardiff, the home of Wales’ national collection of archaeological artefacts. This gives us ready access to the original Iron Age objects which were used at the time that Bryn Eryr was inhabited, as well as to the expert knowledge of curators. We have therefore sought to replicate original artefacts of known provenance using the same attention to detail that would be expected were we to be commissioning replicas for a gallery display. Some examples of the work that has been produced to date can be seen in the images that accompany this article.

The decision to place high quality replicas in the Iron Age farmstead is based on the belief that visitors to open-air museums should experience the same standards as are normal in gallery-based museums, however, the decision does present problems. Security is, inevitably, more challenging in open-air museums and high quality replicas are difficult to replace. Furthermore the wear and tear on items that are in daily use is inevitably greater than on examples sealed in glass cases meaning that the commitment to quality must be coupled with a commitment to a refreshment programme. This will be facilitated through the creation of an interpretation manual for the Iron Age farmstead setting the standard for the presentation and maintenance of the buildings' contents (See Figures 13, 14 and 15).

Conclusion

Through the experience we have obtained from running the old Celtic Village, and the many lessons learnt, we hope that from 2015 visitors to St Fagans will enjoy an introduction to the Iron Age which is of a high and consistent quality. It will be an experience which disabled visitors will find easier to engage with due to the adjustments we have made to the site and which our staff will find easier to manage. With good fortune the Iron Age farmstead will also be a structure which is easier to maintain as a result of the revised building location and construction techniques.

Although the formal opening of the farmstead is still some way off, for many the visitor experience has already begun. Throughout the construction of the site we have drawn on the help of a large number of volunteers from very different backgrounds. Groups from the Probation Service, Hafal (a mental health rehabilitation charity), and corporate volunteer groups have all lent a hand in the harvest of the spelt, the building of the walls, preparing timbers, and thatching the roof. As a result, there is a considerable sense of shared ownership about the project, with many hands contributing to a product which will be enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of people for years to come.

Acknowledgements

The old Celtic Village was open for over twenty years and benefited from the help and support of hundreds of people over that time. The Iron Age farmstead is still being constructed but has already received practical support from almost a hundred volunteers, not to mention the help of many members of staff at St Fagans, and the advice of many external individuals. It will be impossible to mention everyone, but I hope it will not be seen as invidious to highlight a few individuals who have not otherwise been mentioned in this article, but who have been of particular help in developing aspects of these buildings upon which this paper has relied.

The decision to proceed with the building of the Iron Age farmstead was made by John Williams Davies, then Director of Collections & Research in Amgueddfa Cymru. The benefit of help from Andrew Davidson and George Smith of Gwynedd Archaeological Trust in providing access to the Bryn Eryr archive is also gratefully acknowledged. The architectural model for the site was produced by Gerallt Nash, then Senior Curator Historic Buildings at the museum, and building work was carried out by a volunteer team led by members of the museum's Historic Building Unit, overseen by Janet Wilding and supervised by Tony Lewis. Advice on the growing of the spelt and the thatching of the roofs of the Iron Age farmstead was received from John Letts, Reading University, with Andrew Dixie coordinating the crop programme, and Brian Davies managing the farm work. Analytical work in the old Celtic Village relied heavily on the support and encouragement of Penny Hill, then conservator in the museum's Department of Archaeology & Numismatics.

The detailed design and ethos of the build benefited from discussion with Björn Jacobsen of Foteviken, and from the willingness of other members of the OpenArch project to share their own experiences of building and running reconstructed buildings.

A final debt of gratitude goes to Ian Daniel who served as the interpreter in the old Celtic Village for many years, and has been a key figure in the building of the new Iron Age farmstead.

Much of the analytical work conducted on the Moel y Gerddi house and the construction work at Bryn Eryr was carried out with the support of an EU Culture grant. Work at Bryn Eryr has also benefited from grants by Lafarge, the Simon Gibson Charitable Trust, and the Art Fund.

Country

- United Kingdom

Bibliography

CUNLIFFE, B. 1995: Iron Age Britain, London, Batsford.

CUTTLER, R., DAVIDSON, A. & HUGHES, G. 2012: A corridor through time: the archaeology of the A55 Anglesey Road Scheme, Oxford, Oxbow Books.

GUILBERT, G. C. 1976: Moel y Gaer (Rhosesmor) 1972-3: an area excavation in the interior. IN HARDING, D. W. (Ed.) Hillforts: later prehistoric earthworks in Britain and Ireland. London, Academic Press.

GUILBERT, G. C. 1982: Post-ring symmetry in roundhouses at Moel y Gaer and some other sites in prehistoric Britain. IN DRURY, P. J. (Ed.) Structural reconstruction: approaches to the interpretation of excavated remains of buildings. Oxford, British Archaeological Reports.

HARDING, D. W. 2009: The Iron Age round-house: later prehistoric building in Britain and beyond, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

HARDING, D. W., BLAKE, I. M. & REYNOLDS, P. J. 1993: An Iron Age settlement in Dorset: excavation and reconstruction, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

KELLY, R. S. 1988: Two late prehistoric circular enclosures near Harlech, Gwynedd. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 54, 101-51.

LONGLEY, D. 1998: Bryn Eryr: an enclosed settlement of the Iron Age on Anglesey. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 64, 225-273.

People’s Collection Wales 2010: (http://www.peoplescollectionwales.co.uk/items/25575)

SMITH, G. & HARRIS, D. 1982: The excavation of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements at Poldowrian, St Keverne, 1980. Cornish Archaeology, 21, 23-66.

THOMAS, N. 2005: Conderton Camp, Worcestershire: a small middle Iron Age hillfort on Bredon Hill, York, Council for British Archaeology.