The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

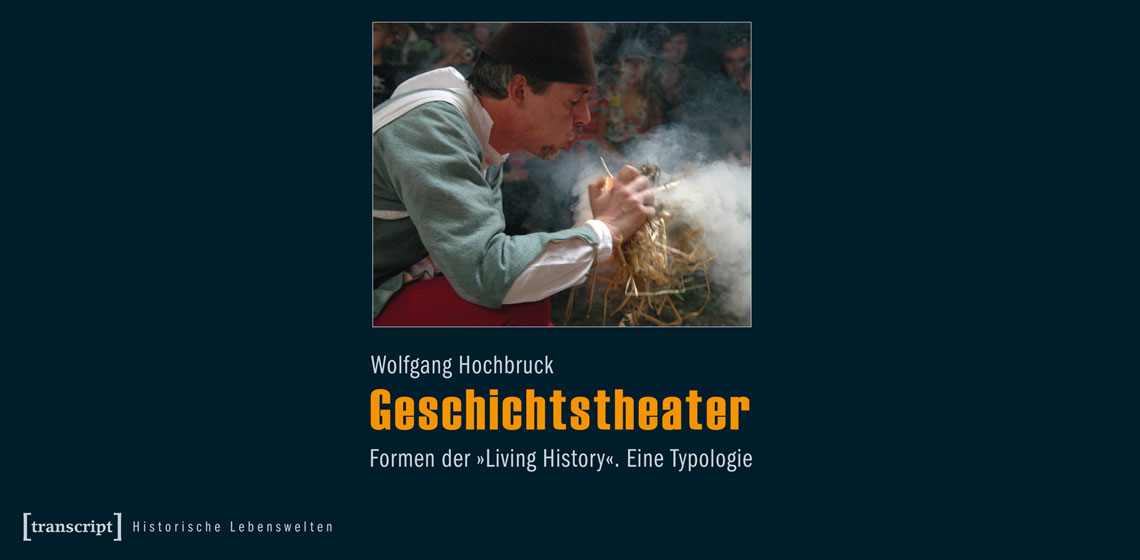

Book Review: Geschichtstheater. Formen der "Living History" by Wolfgang Hochbruck

The dramatisation of history is ubiquitous in our postmodern everyday life: historical novels (as well as their TV adaptations, netting huge audience figures), documentaries, and stylistic references and citations evoking the past in fashion and architecture. The evening news features events such as the 2013 Voelkerschlacht re-enactment in Leipzig, and historical fairs and markets in Germany are as crowded now as regular funfairs have traditionally always been. No wonder that in recent years, German museums, too, are increasingly opening towards alternative means of presenting their content to the public, such as ”living history“ or archaeo-technology, which have long been commonplace in the didactics of museums in the English-speaking world as well as in a variety of European countries.

National interest in re-production of history started when the Ethnological Commission of Westphalia called together with Freilichtmuseum Cloppenburg, one of the oldest German open-air museums, a conference on the topic of “Living history in the Museum” in 2007 in Cloppenburg, Niedersachsen. Subsequent conferences made it clear that - apart from predictable doubts about the reliability and quality of the reconstructions of historical life-worlds and events - there was a significant dissonance regarding terminologies.

Wolfgang Hochbruck, professor of North American Studies at the Albert Ludwigs University Freiburg, has not only been an active agent of the scientific discourse of living history theatre for years, but also a practitioner in a variety of formats from re-enactment to school and museum programmes. Therefore, he is familiar with the debates concerning quality, terminology and definitions. In his book, he dedicates four chapters to pinpointing terminologies and developing definitions of various types of historical re-productions. His assumptions, arguments and conclusions are based on examples taken from the Western world, specifically the English-speaking countries, Scandinavia and Germany.

As a title, and umbrella term, he favours living history theatre as more specific than Jay Anderson’s (1982) term ”living history“, defining the term as encompassing all “forms of presentation and appropriation of historical events, processes, and persons by means of theatre techniques [...] in public or semi-public environments” (Geschichtstheater, p, 11. transl. I.K.).

Among the dramatic techniques are costuming, personalised dramatisation, and mise-en-scène–aspects, which he points out in all the examples presented in the book, though to varying degrees. One by one, he sets out to analyse experimental archaeology, living history interpretation, museum theatre, theme parks, historical guided tours, pageants, medieval markets, re-enactment, live action roleplay, and historical dramatisations as a didactic method in schools, as well as TV shows, and he points out their respective characteristics and traits.

Although the author’s focus is on typologies and the establishment of definitions, the first part of his book offers an overview of the development of the scientific discourse so far, as well as historical re-enactments in general, from their beginnings in antiquity to the present day. The differing intentionalities of practitioners’ and visitors, as well as the political aspects of historical theatre are dealt with only generally. The author, however, himself admits and points out that his field still offers room for much more, deeper and further investigation, even beyond the classic arts and humanities context. Living history theatre is, and should be dealt with, as a broadly interdisciplinary issue.

The quality debate about types of historical theatre in the museum context is not at the core of this volume. However, it is still dealt with cursorily, pointing out quality criteria and stressing educational added value – which is why the exchange between scientists and citizen scholars (which suffered a disastrous decline after a the Paderborn case1 , and after Hochbruck's own research group had their funding cut by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) should be rekindled. More and deeper research is necessary, as the author points out repeatedly, in view of the fact that the average person (as well as the historically interested one) is constantly confronted with re-productions of history.

The numerous anglicisms might irritate some German-speaking readers, but is very much indicative of the current state of research. This is more than compensated by useful graphs and illustrations which are helpful and improve understanding and legibility.

All in all, this book presents a well thought-through piece of research which reflects great knowledge of the subject matter, and is a worthwhile read for connoisseurs as well as interested laypersons. The umbrella term as well as the whole array of terms and definitions favoured by the author might remain controversial amongst fellow-scientists and practitioners. Still, Hochbruck’s commendable work claims the merit of collecting and defining a whole host of different types and terminologies in a manner that provides the basis for a renewed scientific debate on a higher level.

Book information:

HOCHBRUCK, W. (2013), Geschichtstheater. Formen der "Living history". Eine Typologie(= Historische Lebenswelten in populären Wissenskulturen / History in Popular Cultures 10). Bielefeld: Transcript - Verlag für Kommunikation, Kultur und soziale Praxis.

ISBN 978-3-8376-2446-5; 152 S.; EUR 22,99.

- 1During the opening of the Exhibition „A World In Motion“ in Paderborn in 2008, one of the booked actors took off his shirt after a performance and revealed a tattoo with theForbiddenSS-slogan"My honour is loyalty".