The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

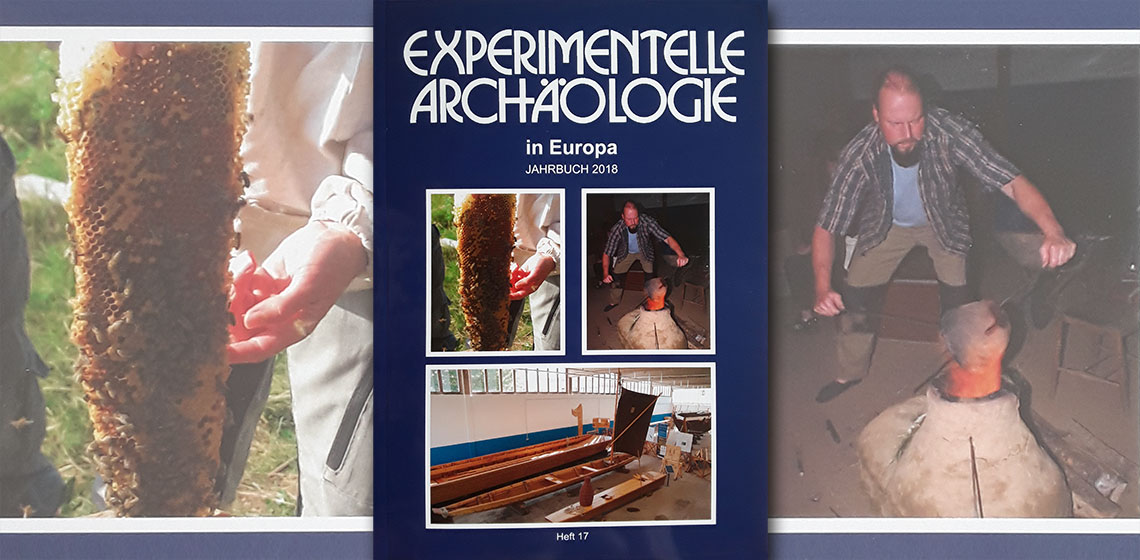

Book Review: Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2018

Like the previous issues, this periodical (Jahrbuch) is published by Gunter Schöbel and the European Association for the advancement of archaeology by experiment e. V. (Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der Experimentellen Archäologie) in collaboration with the Pfahlbaummuseum Unteruhldingen. It is the 17th issue of the periodical and includes 21 essays on 250 pages, presenting the contributions of the EXAR conference from 28th September to 1st October 2017 as well as the annual report (Jahresbericht, p. 245) and the instructions for authors (Autorenrichtlinien, p. 249) of Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa.

The essays are divided into three categories: the first part deals with the experimental side of the archaeology, the second with reconstruction and the third addresses theory. The articles themselves are concise and even for non-specialist of the various fields easy to follow and comprehend. At the beginning of each article is a short summary in English which helps to present the periodical to a non-German speaking audience and for further questions, the contact details of the authors, as well as a selected bibliography, are provided. The articles are completed with coloured pictures and a description in both German and English.

PART 1: Experiment and Attempt (Experiment und Versuch), p.10-109.

There are nine essays in the first part, dealing with a broad spectrum of topics within experimental archaeology; out of those, there are five dealing with Roman heating systems which seem to be the main topic of this part. The articles deal with Prehistoric bee keeping (Prähistorische Bienenhaltung in Mitteleuropa, Sonja Guber, p.10); the tools used for salt mining in Hallstatt during the Bronze Age (Keine Tüllenpickel im bronzezeitlichen Salzbergbau von Hallstatt, Hans Reschreiter u. a., p.19); extendible cement in Roman baths and houses (Auf der Suche nach dem „dehnbaren Beton“, Hannes Lehar, p. 34); the chemical components of Roman screed (Mineralogische und chemische Charakterisierung römischer Estriche, Martin Schidlowski u. a., p. 43); the creation of a recipe for opus caementitium (Rezepturentwicklung von Opus Caementitium zur Verwendung in Hypokaustheizungen, Klemens Meier u. a., p. 50); the experiences of the small Roman baths in Xanten (Erfahrungen aus dem Betrieb der rekonstruierten kleinen Thermen in Xanten, Peter Kienzle, p. 59); the clay industry and furnace technology in and around Mayen (Ofentechnologie und Werkstoffdesign im Mayener Töpferviertel um 500 n. Chr., Gregor Döhner u. a., p. 71); making Roman glass beads at a wood fired furnace (Glasperlenherstellung am holzbefeuerten Lehmofen, Frank Wiesenberg, p.87); and with medieval wire drawing (Überlegungen und Rekonstruktion zum Drahtziehen im Mittelalter, Sayuri de Zilva u. a., p.101).

The first article was the most interesting as it presents a niche and offers insight into a subject that is generally speaking not thought of much when talking about past lives. The experiment is a collaboration with the Open Air Museum Marburger Land and the Bee Institute in Hesse. The main difficulty they are facing is finding the right information as the evidence for prehistoric beekeeping is sparse. There are wall paintings from the Mesolithic period that show how honey was harvested from trees but not whether bees were cultivated by humans. The Neolithic period offers proof that wooden tubes were used as beehives and for the Bronze age there is documented proof of the usage of honey. In 2017, they started with a reconstruction from the first Stone Age finds that could have been a beehive and they were successfully housing an artificial bee swarm. The relocation into another loghive was successful and a 100g of wax could be harvested. During that year, the bees did not produce any honey and the various harvesting methods could not be tested, due to the wet summer; this is a forthcoming project.

PART 2: Reconstructive Archaeology (Rekonstruierende Archäologie), p.110-218.

As in part one, there are nine essays in the second part of the periodical, dealing with “burn-out” as a procedure on building a dugout canoe (“Burn-out” als Arbeitstechnik beim Einbaumbau? Thorsten Heimerking, p.111); the dugout project Ziesar (Das Einbaumprojekt Ziesar, Karl Isekeit, p. 121); Roman ship building (Römische Schiffe im Experiment, Gabriele Schmidhuber-Aspöck, p. 129); reconstruction of a model house in Upper Austria (Die experimentalarchäologische Errichtung der neuen Herrinnenhalle von Mittenkirchen an der Donau im oberösterreichischen Machland, Wolfgang F. A. Lobisser, u. a., p.140); iron age smithy in Lower Austria (Man muss das Eisen schmieden, solange es heiß ist! Wolfgang F. A. Lobisser, p.158); the reconstruction of a scale armour (Gut gerüstet – Der Nachbau eines frühsarmatischen Schuppenpanzers, Clio F. Stahl, p.174); beads in burials and their meaningfulness (Die Spur der Fäden, Maren Siegmann, p.186), the renovation of the „Kaiserpfalz Franconofurd (Alte Mauern mit neuem „Glanz“ – Sanierung und Neupräsentation der Kaiserpfalz, Thomas Flügen, p.199) and how to make good donuts during Medieval times (Wie man guote kraphen mag machen, Andreas Klumpp, p.209).

The title of the last article in this group was most catching. Klumpp started in 2015 with a basic idea of how to interpret medieval recipes and questions occurred about which oil was used for frying, which components are in the dough and whether there were specific tools to make them. The basis for his new experiment is the Medieval Plant Survey database which collects manuscripts in various languages and includes about 2400 cooking recipes in German from the Middle Ages, of which about 87 contain the word “Krapfen”. By analysing the recipes, there are twelve different types of dough that could be identified, about ten different shapes are mentioned, and the oil used varies between animal and vegetable fat. In the future, it is important to test these recipes to see how they work and to see which tools were used to create and form them.

PART 3: Communicating and Theory (Vermittlung und Theorie), p.219-243.

The last part is the shortest of the three, containing only three article; the first deals with communication on archaeological sites (Der Forscher – die Botschaft – der Besucher, Peter Kienzle, p. 220); the second, questions matter in experimental archaeology (Experimentelle Archäologie – Was für eine Frage, Sylvia Crumbach, p. 230) and the third focuses on citizen science in experimental archaeology (Neuer Name – bewährtes Konzept, Claudia Merthen, p. 236).

As the title of part three suggests, it is the most theory based of all three parts in the book, so to speak the theory behind the experiments and reconstruction. It seeks reasons why experimental archaeology is important and what it can tell us when asking the right questions. Reconstructing for the sake of reconstructing can be interesting but it becomes more valuable when a specific hypothesis is raised. To understand the “real” human being, how the average person lived and coped with daily life, is the main focus of many hypotheses. The technology of different time periods always spurs the interest of archaeologist and scientists alike because understanding and the possibility of repeating these early achievements, creates the basis for our modern inventions and even daily life.

A personal -non-academic- highlight in the book was skimming through the pictures and suddenly finding myself in one of the illustrations as part of the Glasofenprojekt 2015 (in Frank Wiesenberg’s article p.87).

All in all, the periodical with its 21 essays gives a broad overview of experimental archaeology and offers a nice overview in various subjects within. It presents studies and experiments that were carried out with a passion and bring the reader one step closer to understanding the lives of past cultures and people.

Book information:

Schöbel, Gunter (ed.), 2018. Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2018, Heft 17, Unteruhldingen: Gunter Schöbel & Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der Experimentellen Archäologie e.V. European Association for the advancement of archaeology by experiment, ISBN: 978-3-944255 – 11- 8.

Keywords

Country

- Austria

- Germany