The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

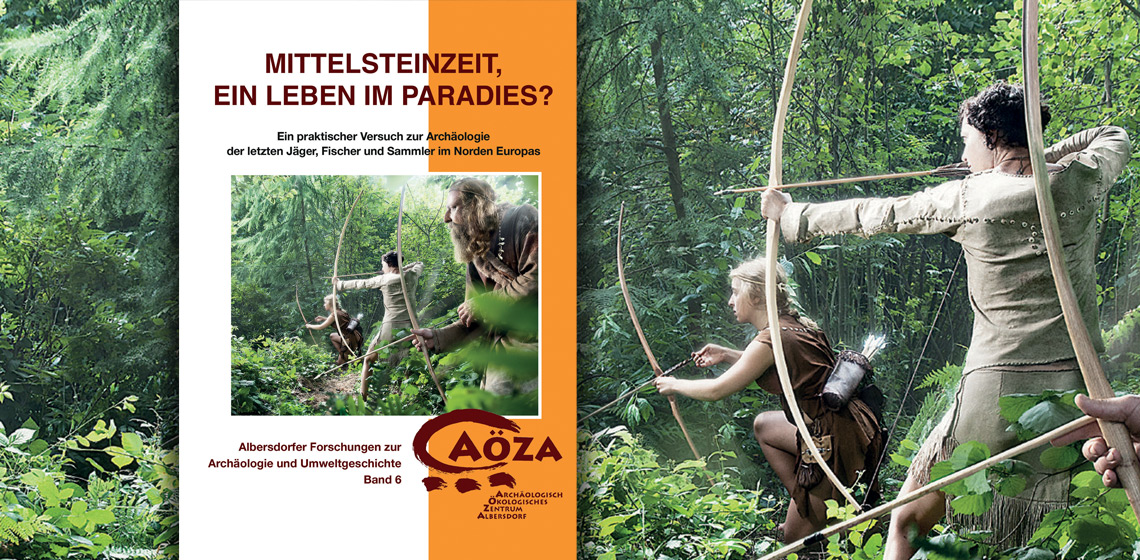

Book Review: Mittelsteinzeit, ein Leben im Paradies? by Werner Pfeifer

Considering actual studies about the analysis of ancient DNA is an important question, if only the lifestyle or the population, too, changed when hunter-gatherers became farmers and stockbreeders. The results point so far towards the latter possibility. However, the foragers of the Northern European Ertebølle culture preserved their lifestyle for one millennium, even though they lived in neighboring areas with the Neolithic societies. It is debatable if the Mesolithic lifestyle and an environment with plentiful natural food resources made it unnecessary for the bearers of the Ertebølle culture to change their ways. In fact, only very little is known about this Mesolithic lifestyle, and the stone artefacts along with a few organic remains, which are naturally preserved, are the sole providers of clues.

To fill these enormous gaps of knowledge and to get at least a vague basic understanding of what Mesolithic life was like, conclusions based on experiments or anthropological studies can be quite helpful. The book Mittelsteinzeit, ein Leben im Paradies is a record of such attempts. In 125 pages, Werner Pfeifer (following: author) presents a collection of pictures and impressions from a project at the open-air museum Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen at Albersdorf (Dithmarschen county, Schleswig-Holstein/Germany). About 80 participants, from scientists to ordinary persons people, took part over the years at the ongoing project which started in 2015, and is connected to the museum’s educational service. This annual event is planned and conducted by the author of the book. The goal of the project is to give the participants a chance to try out the daily life of hunter-gatherers. The scope of the book is to illustrate a selection of the activities and experiences the participants had throughout the event. Additionally, it aims to bring the imagined Mesolithic lifestyle closer to the reader, while also tracing the contrasts to our actual lifes.

The book is not strictly divided into chapters but is organized more around certain topics or terms. It starts with an introduction (p. 9–11) where an overview of the chronology of the Stone Age is traced. With the following topic, named Paradies? (p. 11–14), the author tries to mark the differences between Mesolithic and Neolithic lifestyles. Afterwards, in Die Tierwelt in der Steinzeit (p. 14–17), a selection of Mesolithic fauna is depicted. A short description of the educational projects undertaken at the open-air museum since 2015 is encompassed in the section called Projekte im Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen (p. 18–23). After this introducing part, topics connected to activities (e.g. hunting, fishing, gathering or food preparation), objects and their production (e.g. huts, clothes, pottery, watercrafts, bow and arrow) or art and materials and their processing (e.g. flint, glue, leather or bark) are presented in a loose order (p. 24–113). The last three topics are dedicated to health and healing (p. 114–116) and the consequences of switching to the Neolithic lifestyle (p. 117–119). In an epilogue called Zukunft? (p. 120–121) the author admonishes the reader and humankind in general and urges making changes in their behaviour towards nature.

Overall, this book is a report of the museum showing their activities of the past years with many illustrations. The text is, in most cases, just a support for the images, explaining their content and circumstances in a brief and easy to understand manner. It is not explained in detail how the experiments where prepared, conducted, equipped or how much time was invested. It becomes clear that this was also not the author’s original intention. Several facts and assumptions were connected to scientific contexts and current literature. Often the reconstructions are based on anthropological studies of recent hunter-gatherer societies. The author repeatedly underlines what is known about the Northern Mesolithic, what was only assumed and what was left to imagination. The presented illustrations are of good quality. In a few cases they illustrate certain details, but mostly their purpose is to impress. This includes the depiction of dead animals and their further processing as well as partial nudity in connection to the idea of original clothing.

Besides being an activity report, the author also tries to deliver a message to the reader. In his opinion, the Mesolithic period is comparable to the paradise of the Bible, but this paradise was ended by the arrival of the Neolithic lifestyle (p. 10, p. 117–119). It is debatable if the author’s romantic and harmonic picture of the Northern Mesolithic is real, and if the times were better, easier and healthier. A supposition about why the transformation towards the Neolithic lifestyle was chosen is not offered. If it was not the author’s intention to suggest a return to a Mesolithic lifestyle in order to save the world, the almost politically resonating message of the epilogue is unnecessary and shows no real connection to the book’s content.

In conclusion, the book is neither a lexicon nor a detailed study about the Mesolithic, but it could certainly encourage the readers, who were not involved in experimental archaeology so far, to look for further information or even try it out themselves.

Book information:

Werner Pfeifer, 2019. Mittelsteinzeit, ein Leben im Paradies? Ein praktischer Versuch zur Archäologie der letzten Jäger, Fischer und Sammler im Norden Europas, Albersdorfer Forschungen zur Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte, Bd. 6, ISBN 978-3-89876-973-0, Husum: Verlagsgruppe Husum

Country

- Germany

Bibliography

M. Fraser et al. 2018. New insights on cultural dualism and population structure in the Middle Neolithic Funnel Beaker culture on the island of Gotland. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 17 (2018) 325–334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.09.002

Lazaridis et al. 2014. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513: 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13673.