The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

A Course in Experiential Archaeology at an Archeopark as a Part of Active University Education

As with any other science, archaeology constantly adopts new methods and trends over time. University education in the field can be very helpful advancing sciences in every country. This type of education influences the early stages of future top scientists and forms their future careers. Therefore, education should reflect not only scientific innovations but also innovative educational methods. In archaeology we do not often incorporate such an approach. We all know from our own experiences, though, that playful diversions can bring positive results, regardless of the students’ age.

It is especially surprising that within the framework of technology and life throughout prehistory that educational presentations are often delivered only through text, photos of finds, and black and white pictures. We therefore decided to try a hands-on learning approach of chosen technologies in the form of an open-air experiential course to engage archaeology students. In cooperation with three institutions: Ústav archaeologické památkové péče středních Čech (Institute for Preservation of Archaeological Heritage of Central Bohemia, www.uappsc.cz), Ústav pro archeologii FF UK (Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts Charles University in Prague, www.uprav.ff.cuni.cz) and Bacrie society (non-profit voluntary organisation, which runs the open-air museum Křivolík in East Bohemia, www.krivolik.cz), we organised a Course of Experiential Archaeology. The course was supposed to offer students not only new ways of learning, but also to help us test our educational theories. These will be described in the second part of the article.

Course of Experiential Archaeology

The Course of Experiential Archaeology took place from 21 to 24 June 2016 in the open-air museum Křivolík near Česká Třebová in East Bohemia. The term 'experiential' was used deliberately. It was introduced into Czechia by Zdeněk Smetánka (Smetánka 2000) to express the ability of experimentation to give people experience. The aim of experiential archaeology, therefore, is not a verification of a concrete hypothesis by carrying out an experiment following strict rules and using authentic tools and methods, but to give a deeper understanding of the past. This is attractive not only for the public but also for archaeologists themselves. If they can, for example, try to make knapped stone tools or smelt bronze with their own hands, then they can then better understand the process which could later influence their scientific conclusions. At the beginning however, the term was a bit difficult for the students to understand. We have used it mostly because of the raging academic disputes over experimental versus experiential archaeology (for example Tichý 2005), and we will discuss its suitability and possible alternatives later.

The maximum number of students was, for practical reasons, set at 15 to 20. We expected that the interest would be low, and were therefore very surprised when we received applications from 20 students from various Czech Universities and secondary schools. Due to either personal or health reasons, however, only 15 applicants participated, which showed itself to be the optimal number of participants for such a course, both from a practical point of view and in fostering a friendly atmosphere.

The whole course was based on a professional approach, both from an organisational and educational point of view, and therefore, we tried to choose enough experienced instructors. If we had decided to run the course with only two people we would have still given the students new knowledge, but it would not have been possible to cover all of the planned blocks and study each topic in depth. We also presumed that during the course the students would come up with new ideas and questions, and therefore, we prepared for them free worksheets. These presented basic aims of the course, along with a glossary, suggested reading, instructors' contact information, and also space for their ideas. This space was divide for each topic into 'What I have gained', 'What I have learned', 'What I was good at', 'What I was not good at' and 'What crossed my mind on the given topic'. These questions were supposed to help students create their own views.

The topics of the programme were divided into several thematic blocks. Thursday evening was dedicated to learning about the environment of the open-air museum Křivolík. Around a bonfire we talked to participants about what had caused them to take part in the course, what did they expect, what was their archaeological experience, and this also allowed us to explain to them the aims and a programme of the course. From the very first morning, they dove into prehistory and concentrated on single technologies. The participants were divided into three groups of five so that the groups could take turns at the various stations.

The Friday morning block combined pottery making with textile fibres work, with the afternoon then focused on the production of glass beads and textiles. Pottery and glass bead making was lead by ceramist Monika Maršálková. Textile production was supervised by archaeologist Kristýna Urbanová. She guided students through textile technology, starting with working vegetable and animal fibres, through spinning, and on to weaving accessories on card or comb looms. The third activity of the day was preparation construction work for a log hall based on Bronze Age finds. Some of the participants tried wood working tools (like a drawknife or an axe) for the first time and experienced the technological demands of prehistoric and medieval building construction. Saturday was dedicated to ancient technologies. The day was divided into three blocks. One was supervised by Petr Zítka, a knapped industry specialist. During the day he taught the participants basic techniques and terminology. The demonstrations resulted in stone tools that participants could keep as a reminder of craft advancement in early prehistory. In the second block, stonemason Jaroslav Fieger led participants in the polishing, drilling, and cutting of stone. Although he is not an archaeologist, thanks to detailed studies of finds, and using archaeological and ethnographic literature, he has a thorough understanding of the possibilities in using prehistoric techniques. The third block was less physically demanding but required precision. It was dedicated to working plant material into vessels, cases, and accessories. It was led by a professional teacher experienced in primitive technologies, Eva Pecháčková. She showed the students what prehistoric people could make from bark, reeds, grass or straw, and taught them some of the techniques.

We also wanted to show them that prehistory was not only work, that it was also filled with celebrations and rituals. As this course will have changed many of the participants' views of archaeology, and in some cases, maybe also their future specialisation or leisure interest, we wanted to crown everything off with an initiation ritual. These have been a part of all societies, and are still present, albeit in restricted form, in our own. On a hot Saturday night, we changed into costumes which we used during public events, made a big bonfire and brought the participants to it. Each participant was marked with an initiation sign and had to sacrifice to the fire some of their personal belongings, thus symbolically getting rid of one of their fears. As a proof of their spiritual change, they all walked over the fire and, with self-made musical instruments, they joined in with the speeding rhythm of drums. In a playing and undulating circle, we stirred up the flames while local Křivolík boys started to jump through the high flaming bonfire. The sparks it spat at first made the participants uncertain but the thickening atmosphere soon made them fly through the heat as well. The experience, strengthened by the surrounding deep woods and star-lit night, left everybody with an intense memory. From the point of view of experiential education, such activity is not only a unifying communal element but also an integral part of the education programme. It gives the participants a deep, personal, and non-transferable experience which they will remember, and which would be positively connected to both the event and the knowledge gained.

The whole course was free. It was financed by the Ústav archaeologické památkové péče, open-air musem Křivolík, and the patronage of the council president of the Pardubice region. Therefore, we decided that in return we would use the Sunday morning to help daub the Hallstatt house of a potter. Daub is one of the most common archaeological finds, and so the participants could see with their own eyes how it is made. The construction work was interspersed with bronze smelting which was led by Jan Havelka, a student of archaeology from Masaryk University in Brno. He showed the participants that it is possible to pursue experimental archaeology while studying.

As this course was the first of this type in Czechia, feedback was crucial. We did not want it from the participants directly at the end of the course while they were still overloaded with information and experience. We wanted to give them time for absorption. Therefore, we sent them electronic evaluation questionnaires a week after the end of the course. We prepared them with the help of Google Forms, which creates forms online for free and immediately prepares graphs from the answers. Evaluation should be a natural part of all education, with the results used in creating new educational activities (Brockenmeyerová-Fenclová et al. 2000, 25).

We sent the questionnaire with 14 questions to all 15 participants, ten of them responded. Therefore, we know the views of two thirds of the participants, which we consider relevant feedback. As it is a statistically small sample, we did not need any complicated analytic methods, but could rely on direct evaluation. This evaluation gave us not only important insights into the participants' views of the whole event, but also proved important for describing the theoretical framework of the educational approach. These results will be incorporated when planning not only for the coming years, but also for other similar activities.

The first question asked was where the participants had learnt of the course (See Graph 1). Surprisingly 70% answered 'from a friend'. It seems that information on unusual events spread within the academic circles on their own, and that personal contacts may be a more effective form of advertising than official invitations. With the second question, 'What did you expect from the course?' we wanted to find out why the participants decided to spend a free weekend practicing archaeology. We were pleased that their expectations coincided with our aims. A sample of answers included:

"New knowledge from the field."

"That I would try various prehistoric technologies and crafts."

"Practical demonstrations of theoretical techniques."

"New knowledge and experiment."

"New contacts and experiences, different view of work with people."

"Pleasantly spent weekend, possibility to learn in practise what we are taught about."

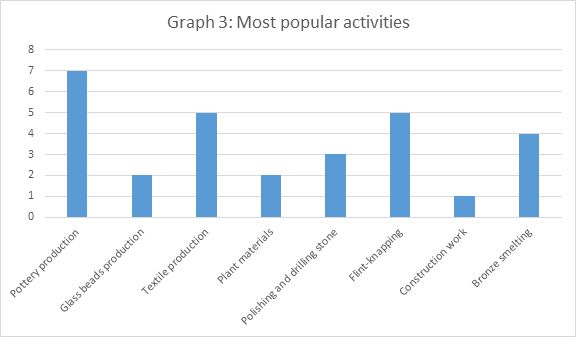

The answers to the third question, "Did the course fulfil your expectations?", pleased us very much as the answers were 100% "yes" (See Graph 2). The fourth question, "What did you like the most/ what would you like to return to?", offered an interesting spectrum of answers. The participants could tick up to three possibilities because it was clear to us that choosing only one activity could be very difficult (See Graph 3). It is clear from the results that pottery production was the most successful, maybe because of its accessibility and visible results without having previous experience. The second most popular activities were textile production and knapping, the third was bronze smelting and coin minting. In the fourth place was polishing and drilling stone, in fifth place, glass bead making and work with plant materials. Construction work received only one vote, maybe because in comparison to other educational blocks it was more like work rather than learning. It is very good to see the reactions because we can conclude what is attractive to the participants based on their own views and not from our view, which is influenced by our knowledge, experience, and personal preferences.

We also wanted to know if the course changed the participants' view of archaeology. We expected negative answers but 30% answered "yes" (See Graph 4). With the next question, "In what way", we wanted to specify the answers. Again we have chosen the most interesting ones:

"I think I glimpsed the experiential archaeo-field a bit before so the change was not distinctive. It was more a great delight that I finally got the possibility to experience it. It was definitely interesting to see what sorts of objects can be made from plant materials – they mostly do not survive. Although archaeologists know it is still interesting to see it."

"Archaeology is super, this course confirmed it."

"It energized."

"It made my interest deeper."

"I can empathise more with thinking and production techniques of given people."

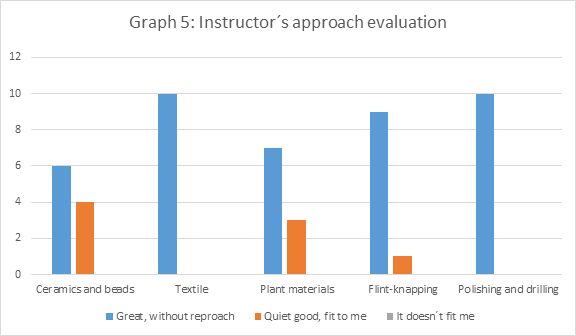

Although we were confident about the high quality of our instructors, it was necessary to learn the views of the participants and find out how they would evaluate the instructors' approaches. Their approach was accepted without reproach (See Graph 5), which was very important feedback for both us and the instructors.

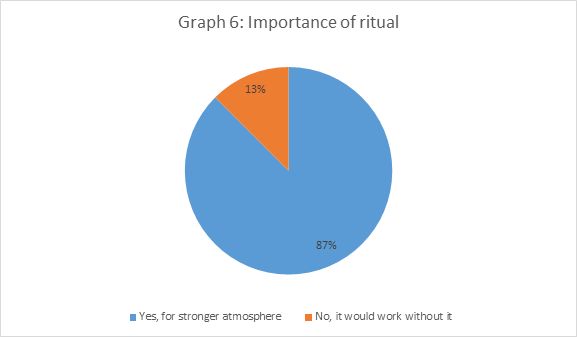

The ritual, maybe a bit of an untraditional part of an education course, could have evoked negative reaction from the participants. We decided to find out if the ritual was an important and beneficial part of the course. We were pleased when nearly seven participants said "yes", it strengthened the atmosphere and deepened the experience. Only one participant said that the course would have been good even without the ritual (See Graph 6). Two participants did not answer.

We were also interested to know if the participants saw Křivolík as a suitable environment for organisation of the course. Ninety percent answered yes, 10% answered no. This is a very important result for us because we care about the participants' personal experience. On the other hand, we need to consider the fact that evaluation of the place is truly subjective. The process of 'pulling participants out of civilisation' plays an equally important role of impacting participants' feelings. It is important for becoming aware of many aspects of prehistoric life.

Two questions from the questionnaire, "What would you improve for next time?" and "How do you rate the overall organisation of the course?" (using a scale from A to D, A being the highest), had purely practical aims and were very important for us from an organisational point of view. We were pleased that 70% of participants rated us 'A' and 30% 'B' (See Graph 7). As far as suggestions for improvements, the main reproach concerned midday meals, which we had to change at the last possible moment and that had caused time complications, which we were aware of. Among the notes there was an interesting suggestion that gave us inspiration for future thinking:

"There is not much to improve; rather there are many more possibilities to try concerning prehistoric life. We could experiment with prehistoric food, dying textiles or carving bowls and spoons. Some activities could have been longer so the participants could try them better (for example pottery, it would be interesting to follow through from the beginning – from clay processing and tempering to firing). Would it also be possible, if the people showed interest in advance, to create their own costume? (If they chose and paid for the material.)"

The last three questions present a summary of the whole questionnaire and give us important food for thought that should be considered while planning archaeological university education and during general theoretical considerations in archaeology. To the question "Should such practical demonstrations be part of archaeology university education?", 100% responses were "Yes, definitely, they give archaeology another life and needed dimension". Similarly in the case of the question: "Could, according to you, experimental archaeology significantly help our field?", there was again 100% 'yes' response, "Yes, experimental archaeology is a method, which can truly bring and verify new substantial hypothesis there, where the finds remain silent." The last question, "What did participation in the course give concretely to you?", was also positive with examples of responses given below:

"Much information and experience."

"Apart from elation from trying the activities it was also astonishing what a great place Křivolík is! And also inner question and debate about what material I should archaeologically focus on."

"An idea about possible methods and techniques used while making (anything)"

"It opened my horizons."

"A pleasant company, new knowledge. Nice experience"

From the running and evaluation of the course we gained many interesting ideas, which we would divide into two groups. The first concerns archaeological university education, and the second concerns experimental and experiential archaeology itself in general.

Active Teaching as an Innovative Part of Archaeological University Education

A university course aimed at teaching prehistoric technologies would be unusual within the Czech environment. As has been shown however, students are very appreciative of the possibility to compliment the mostly theoretical knowledge with practical experiences. There is, of course, the field practice, which is compulsory for all students and is a significant part of archaeological education. On excavations, students encounter real archaeological finds and situations, and they learn to solve them and acquire basic skills needed in their profession.

On the other hand, there should also be learning about archaeological finds in their original live forms and function. Ethnoarchaeology established itself in this field in the second half of the 20th century (David & Kramer 2001, 6). Its complicated theories and, in the Czech environment, problematic application, can be difficult to understand for students at the beginning. To leave out the study of 'live' prehistoric cultures from education completely, concentrating only on studying the 'dead' reflection, is not possible any more. The door into this world can be opened by experimental or experiential archaeology, which can present much archaeological information through personal experience.

There are no doubts about the importance of tangible educational aids. Comenius already reminded us that it was very useful to show pupils many things directly in the shape of collection exhibits (Jůva 2009, 283). In archaeological education, this functions through the principle of artifact teaching. It is based on the premise that while studying an artefact, people do not learn only about the artefact itself, but also about the time of its origin, and that they learn to think critically and see the issues from many angles (Jagošová et al. 2010). If we widen the study of artifacts by discovering the principles of their origin, we gain an effective tool that allows us to present large amounts of archaeological information, from use of various materials through technological innovations, to further possibilities in interpretation.

This need for educational methods that can transfer abstract academic ideas into the concrete practical realities of human life has been in university education for a long time. Many students are not fully accustomed to a textbook-based method of education, and they create their own distinctive approaches to learning, so the possibility of a work-study programme is an important experience for them. It allows them to use their own practical experience, in combination with testing, and the application of ideas discussed within the university environment (Kolb 1984, 6). The difference in the approaches to learning is obvious. Within university education, where the approach is that students are a passive, tabula rasa, empty vessels to be filled with information by the teacher, still prevails. On the other hand, there is an active approach to learning when every student is involved in the interaction – they react to an environment where they learn, to the teacher, to artifacts and to other people. Their own experience is then equally important (Oltholf 2012).

Such a transfer of knowledge is unlike the traditional university teaching based on constructive methodology. Constructive methodology is based on the educational theory of constructivism that developed from the beginning of the 20th century. It is still one of the most effective educational methods used within the heritage sector and in museological education. Constructivism is based on the students' active participation in the education process. The education is not aimed so much at the curriculum as at the student. They acquire new information by mostly gaining it themselves and it allows them to build on what they already know (Hooper-Greenhill 2004, 79). Examining and testing various prehistoric technologies with their own hands is a great example of the combination of an artefact with constructivist education in archaeology.

University education based on analysing presented information can also use the fairly modern educational methodology of 'problem-based learning', where students gain new knowledge by problem solving. This methodology is also starting to be used in archaeology (for example Wood 2013), and in the case of experimentation, is very suitable. Thus a well-designed educational project motivates students to develop their own basic skills via teamwork, communication, critical analysis, and problem solving. The students lead themselves through the education process and they should be able to independently plan an experiment, carry it out, and publish it. This also demands that they believe in their own research capabilities and are able to recognise abilities suitable for further career development. If we look at the results of the evaluation of the Křivolík course, we find that the course gave some students answers to many questions concerning, not only past, but also their future specialisation. We can therefore influence not only the students' knowledge and skills, with a combination of modern methods and participative and co-operative ways of teaching, but also their later employment, and professional and personal development. The rising number of museums and archaeoparks also means rising number of job offers, education in the field of practical skills suitable for educating the public will have more and more use. For example, in the oldest open-air museum, Swedish Skansen, they have a special programme aimed at educators. Educational officers are recruited every year, they should have an academic background and they have to pass specialised craft training. Emphasis is on mediating information and knowledge, not on production and sales (Olthof2012). Students are more than welcome, and for them it means not only useful practice but also the first step of their career.

Open-air Museums and Student Education

Experimental archaeological courses for university students in Europe have a rich history. For example, educational historical and archaeological workshops have become an integral part of the oldest experimental centre in Danish Lejre. Here, experienced instructors and archaeologists interpret cultural-historical knowledge by letting students carry out activities, which used to take place in the past. The fact that it is happening within a reconstructed environment offers conditions supporting identification with the past. Identification and absorption are two key concepts, which they were striving to achieve in Lejre (Bay 2005, 49). They are very important, not only for general visitors, but also for the archaeology students themselves. Here, we return again to our evaluation by our participants, where 90% of them agreed that an archaeopark environment is truly suitable for this type of course.

A strong argument for the application of active teaching of prehistoric periods in the archaeopark environment is also the fact that archaeology usually sees a drastically reduced form of the past living culture: what we get in our archaeological sources is only a fragment of what used to exist originally. Therefore, archaeological models should be attempting to record and correlate this quantitative misrepresentation. That is possible only if the researchers have an overview of the possibilities of the wide spectrum of finds mostly unnoticeable through traditional excavations (Neustupný 2010, 29). Thanks to experimental archaeology, and applying the findings of ethnoarchaeology, students can get a clearer image of the richness of past living cultures, as again was shown from their own experience within the course.

Such experiential programmes are mostly used in presentations for the greater public. They offer visitors experiences that are often the reason for their visit – they want to see something, to experience something. And for us, that is what open-air museums should be offering; not only to the lay public but also to the professional public. In the example of the Křivolík course, we can see another benefit – in comparison to other Czech archaeoparks it does not have the usual background (it's missing a modern building, electricity, strong mobile signal, et cetera), and over a longer stay, it offers a deeper experience and connection to nature. Such a place gives them a story and pulls them back thousands of years, to where they are not only observers, but participants in the happenings. They experience their roots and gain respect for the past. A theoretical archaeological lecture here comes into sharp contrast with reality and this is suitable, or even desirable, for archaeology university teaching. Through a longer stay in an open-air museum, students can become more aware of the meaning of archaeology and ponder the nature of their own future research. At the same time, they not only learn about life in the past but they also understand how to specify its interpretation (Colomer 2002, 92).

The environmental dimension of such a course is also an essential element. As landscape has influenced people and vice-versa, open-air museums are provided with an opportunity to reflect this influence (Maršálek 2014, 43). That is another aspect, which serves as an illustrative example of the wide ranging archaeological theories based on natural scientific analyses. Archeoparks and open-air museums can show intangible knowledge and make it tangible. They can deal with both what we know and what we do not know. That is their unique contribution to educational activities (Hurcombe 2015).

It is not only about newly acquired knowledge and skills, however, but also newly acquired contacts and meeting with people whom students would not otherwise meet within an academic setting that is also important. Whether these are archaeologists from further regions or craftsmen and archaeotechnicians who might not be professional scientists but who have worked with prehistoric technologies at the top level for many years. An essential contribution is also meeting students from other universities and departments that gives a multidisciplinary overlap. Ideas and feelings of young people can resonate among them and thus move them in new directions. A combination of new and active educational methods, with strong personal experiences, opens archaeology students to a new perspective of their discipline. Learning this way is changing into an active process that changes students.

Experimental versus Experiential – How to Not Get Lost Within the Labyrinth of Terminology

Organising the Course of Experiential Archaeology reminded us of the persistent issues surrounding terminology. The participants themselves were confused by the term 'experiential', as most had never encountered it before. They connected the activities we carried out within the course with the term 'experimental archaeology'. In academic circles this term is seen as a strictly scientific methodology with rules against attempting already researched methods. Archaeologists dealing with experimental archaeology feel that the multiple terms are detrimental.

This problem has been discussed for many years all over the world and within the context of education (in Czechia see for example Dočekal 2012). Here the term 'zážitková pedagogika' - experiential teaching is used. It covers the various trends, most of which are not theoretically anchored. The problems with the term 'experiential' was pointed out in the 1980's by David Kolb, who in connection with the term 'experiential learning' presents two separate meanings. The first one, he describes subjectively as "the experience of joy and happiness" (it would be translated into Czech as zážitek, prožitek). The other is an objective meaning, connected to the environment, depicted by "20 years of experience" (in Czech zkušenost) (Kolb 184, 35). If we would like to translate the term 'experiential archaeology' into Czech, we run into a problem – zážitková or zkušenostní? Both terms are misleading and do not describe the substance of what is happening within the activities.

In the archaeological community an online debate on this topic took place in 2014 in the Facebook group 'Experimental Archaeology'. An excerpt of this debate was later published in the EXARC Journal. From our point of view, the most interesting argument was presented by Edwin Deady: “It seems that an experiment requires information as a base that is actually often unavailable and can only be gained by ‘experiential’ archaeology. People trying the tools, going on the journeys etc. This being so, it seems odd to criticise the experiential or to label efforts as such in derogatory terms when an experiment is impossible without it.” (Deady 2014). Every archaeologist pursuing experimental methods would surely confirm that attempting and repeating concrete technology brings new questions, that can than lead to further experiments. Where is the border between experimental and experiential archaeology? To admit that the issue is too complex to strictly divide scientific experiment (which is influenced by the human factor anyway) from experience seems to be a reasonable compromise. Experience is an integral part of archaeological experiments (Tichý 2005). The main aim of experimental archaeology is to understand how prehistoric artifacts were made and used. That includes reconstruction of artefacts using the same techniques and materials utilising the latest archaeological knowledge (Forrest 2008, 87). Attempting to reach this knowledge without having experience within the given activity itself is erroneous. Therefore, archaeologists work today with experienced craftsmen who are not archaeologists but who can enrich our theories and hypotheses with their practical knowledge. Unfortunately, existing experiments are still inadequately represented in publication of academic research. It seems there is a chasm between people with practical skills, who have mastered primitive technologies, and strict academics. This chasm should be bridged so that the existing treasure of practical knowledge can be used in archaeological research (Outram 2005, 44) because, for us archaeologists, it is a whole learning process and a collecting of experience which leads to new knowledge and new points of view.

As we can see, the terms ‘experimental’ and ‘experiential’ archaeology are closely related and there is the question of whether it is really necessary to separate them. It would be possible to object that experiential archaeology is more often used as an effective method of archaeological presentation and popularisation, and therefore it cannot be connected to scientific experimental method. However, that would also mean that popular archaeology cannot use terms like field, prehistoric archaeology or archaeological survey because the public does not carry out field archaeology, they only occasionally try it. We see we can go on ad absurdum within this debate. As archaeology progresses, not only with new theoretical but also methodological approaches, which also concerns education whether within the profession or towards the public, it is necessary to consider the whole issue comprehensively. We should slowly free ourselves from the original conception of experimental archaeology and accept that it represents a much wider range of activities than we are prepared to admit now.

Conclusion

The importance of experimental archaeology within the heritage sector cannot be doubted. It fills gaps in our knowledge of the past. Its ability to test ideas based on archaeological sources and their placement within historical context can often give us a much better image of past life, whether we are specialists or the general public. Experimental archaeology should also have its place within archaeology university education. It can, on the principle of active and experiential teaching, open new ways of prehistoric research and in a practical way bring nearer the knowledge gained from lectures and books. The unquestionable benefit is also the subjective side of personal development. Thanks to active teaching, we can lead students to reflection on the life of our forebears, our own life, and to an assessment how we would like to live in the future.

The Course of Experiential Archaeology for Czech archaeological students is an example of application of the hypothesis outlined in the article. It brought together many theoretical questions, among those of which was the problematic term ‘experienciální - experiential. All ideas presented within the article should be a subject of further discussion.

Country

- Czech Republic

Bibliography

BAY, J. (2005). Představení dánských historických workshopů. Živá archeologie 6, pp. 49-50.

BROCKMEYEROVÁ-FENCLOVÁ, J., ČAPEK, V. , and KOTÁSEK J. (2000). Oborové didaktiky jako samostatné vědecké disciplíny. Pedagogika XLX, pp. 23-37.

COLOMER, L. (2002).Educational facilities in archaeological reconstructions. Is an image worth more than a thousand words? Public Archaeology. (2), pp. 85-94.

DAVID, N. and KRAMER, C. (2001). Ethnoarchaeology in Action. Cambridge University Press.

DEADY, E. (2014). Discussion on Experimental versus Experiential Archaeology. [online]. EXARC Manuals [cit. 2016-09-22]. Accesible z WWW: http://journal.exarc.net/issue-2015-1/mm/discussion-experimental-versus-experiential-archaeology

DOČEKAL, V. (2012) Prožitkové, zážitkové, nebo zkušenostní učení? e-Pedagogium. 1/2012, pp. 9-17.

FORREST, C. 2008: Spojení experimentální archeologie a living history ve sféře kulturního dědictví.Živá archeologie. REA. 9. pp.87-90.

HOOPER-GREENHILL, E. (2004). The Educational Role of the Museum. London/New York.

HURCOMBE, L. 2015: Tangible and Intangible Knowledge: the unique Contribution of Archaeological Open-Air Museum [online]. EXARC Journal. 2015/4. [cit. 2016-08-22]. Accesible z WWW: <http://journal.exarc.net/issue-2015-4/aoam/tangible-and-intangible-knowledge-unique-contribution-archaeological-open-air-museums>

JAGOŠOVÁ, L., JŮVA, V., and MRÁZOVÁ, L. (2010) Muzejní pedagogika. Metodologické a didaktické aspekty muzejní edukace. Brno.

JŮVA, V. (2009). Mimoškolní edukační média. In: Průcha, J. (ed.), Pedagogická encyklopedie. Praha, pp. 282-286.

KOLB, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience As The Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs.

MARŠÁLEK, D. (2014). Šíře poslání muzeí v přírodě. Rekonstrukce a prezentace archeologických objektů III, pp. 42-45.

NEUSTUPNÝ, E. (2010). Teorie archeologie. Plzeň.

OLTHOLF, D. (2012).Adult Education in Archaeological Open-Air Museums. [online]. EXARC Manuals [cit. 2016-08-18]. Nestránkováno. Dostupné z WWW: http://exarc.net/manuals/adult-education-archaeological-open-air-museums-reader

OUTRAM, A. K. (2005). Magisterské studium experimentální archeologie na Exeterské univerzitě. Živá archeologie. 6, 44.

SMETÁNKA, Z. (2004). Archeologie a experiment. Dějiny a současnost. 22, pp. 2-5.

TICHÝ, R. (2005). Presentation of Archaeology and Archaeological Experiment. EuroREA 2/2005. Pp. 113-119.

WOOD, G. (2013). Let´s Build a Medieval Tile Kiln – Introducing Experimental Archaeology into theUniversity Curriculum [online]. EXARC Journal 2013/2 [cit. 2016-08-16]. Dostupné z WWW: <http://journal.exarc.net/issue-2013-2/ea/lets-build-medieval-tile-kiln-introducing-experimental-archaeology-university-curriculum>.