The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

What was *platъ and how Did it Work? Reconstructing a Piece of Slavic Cloth Currency

Using a credit theory of money, we propose that at least some Slavic tribal communities underwent a process of social monetization. In order to fully support this hypothesis, however, many linguistic and historiographic sources would need to be discussed – a task which exceeds the scope of a single article. Therefore, we will here focus on examining (from technical perspective) the oldest type of “money” mentioned by Slavic tribal communities, which we interpret as physical records of mutual obligations.

Introduction

There is rare but clear evidence that at least some early medieval Slavic communities used pieces of textile during the exchange of goods. The written sources (transcription of the notes of Ibrahim Ibn Yaʻqūb and a short notice made by Helmold of Bosau nearly two hundred years later) entitle us to believe that it was some kind of currency and not a local predominant commodity. In general, we also do not assume that money is generally evolved from goods in societies, as the economically orthodox theory argues, for which the credit theory of money is a suitable explanatory alternative.

The Mysterious Currency of the Ancient Slavs

Our experiment has two main goals:

- To reconstruct a piece of Slavic textile currency based on descriptions from written sources. We call the product *platъ, which means “a piece of cloth” in Proto-Slavic (Rejzek, 2015, p.495).

- To justify the hypothesis of the functioning of *platъ according to a credit principle. There is no consensus on how and why *platъ represented an economic value among the ancient Slavs. According to our hypothesis, the *platъ was just a tool for recording mutual obligations. Our argument for this is primarily etymological.

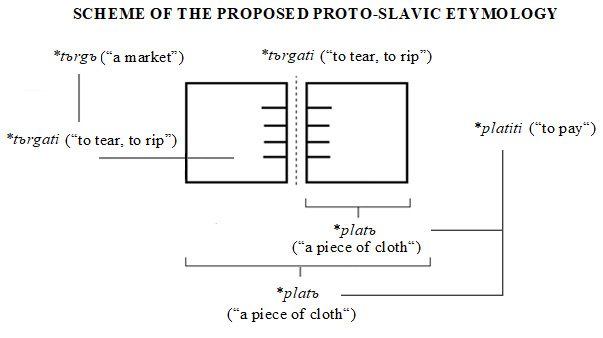

In Proto-Slavic, the word *platъ (“a piece of cloth”) is etymologically related to the word *platiti (“to pay”). The relation is explained precisely by the using of pieces of cloth for paying by the old Slavs (Rejzek, 2015, p.495).

However, there is another word connected with trade in Proto-Slavic, this time of unclear origin. The word was *tъrgъ (“a market” - the act of trading) and it has many descendants in modern Slavic languages, meaning “a market”, “a marketplace” or sometimes even “merchandise”. The expression even affected some non-Slavic languages (see Vasmer, 1987, p.82; ESJS, 2012, pp.990-91).

Various theories explain the origin of the expression *tъrgъ. They suggest a pre-Indo-European Mediterranean origin, a Turkic origin or even an Archaic Mesopotamian origin, but there is not an agreement among scholars so far. However, none of these theories take into account the *platъ currency.

According to our hypothesis, the word *tъrgъ is also of Proto-Slavic origin and refers to the way in which *platъ was used. The Proto-Slavic verb “to tear/to rip” was *tъrgati (see Rejzek, 2015, p.708). It is nearly the same word as the noun *tъrgъ (“market”1 ).

According to our opinion, the *platъ was relatively an ordinary piece of cloth. Neither the material nor the method of production indicates that this was an extraordinary valuable thing. Concurrently, it cannot be assumed that the production was controlled by a center of power (compare with Jakimowicz, 1948, pp.453-454). If there is no indication that the *platъ was a centrally produced currency, or that it had any intrinsic value, only one conceivable option remains: it must have consisted of a kind of archaic bill of exchange. The *platъ was just a tool for recording mutual obligations during the exchange of goods.

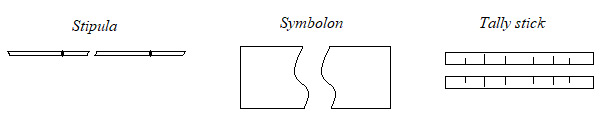

There are many ways to record mutual commitment by dividing a thing into two identifiable halves (by tearing in our case). Some reports on the various practices used for this purpose by ancient, medieval or indigenous nations exist (Mauss, 1999, p.127). In Symposium, Plato ended one of his poetic myths by referring to the symbolon:

ἕκαστος οὖν ἡμῶν ἐστιν ἀνθρώπου σύμβολον2 (191d)

Symbolon was the item, which was used to symbolize a deal. This could also be achieved by breaking an object into two identifiable parts. It could be a bone or a clay token. The broken parts served as a contract for the right to hospitality, some service or a thing in general (Hopper and Millett, 2016; Shell, 1989, pp.39-40).

Another example is provided by Isidore of Seville. He mentions the institution of stipulatio in the 5th book of his Etymologiae (5.24.30). Two halves of a broken reed were used in this case to identify the contract:

Stipulatio est promissio vel sponsio; unde et promissores stipulatores vocantur. Dicta autem stipulatio ab stipula. Veteres enim, quando sibi aliquid promitebant, stipulam tenetes frangebant, quam iterum iungentes sponsiones suas agnoscebant (sive quod stipulum iuxta Paulum iuridicum firmum appellaverunt)3

Probably the best-known and widespread tool for recording obligations was the tally stick. They were wooden pieces with engraved notches and served to record a loan and a debt. The notches (or the spacing between the notches) on the sticks represented the specific amount of economic production or even the amount of days of compulsory work required by the creditor (Henkelman and Folmer, 2016, pp.143-150).

The basic functional principle of the symbollon, the stipula and the tally stick was the creation of two identifiable parts, two halves forming a portable contract with a chance for the owner to submit his right to demand a service or payment. The owner’s half of the symbolon, stipula or tally stick could function as money (a credible representative of economic value) in specific social conditions.

There is linguistic trace that the Slavic *platъ worked on a similar principle. We can suppose that the noun *tъrgъ (“market”) is derived from the verb *tъrgati (“to tear/rip”), and that the meaning of *tъrgati platъ (“to tear the piece of cloth”) is the making of a market contract:

The “bill of exchange” principle (the credit theory of money) was not considered as an explanation for the use of *plat currency until the hypothesis outlined here (for the full discussion see Kratochvíl, 2020, pp.220-225).

We tried to gather the available information on what the *platъ may have looked like so that we can reconstruct it and verify its suitability for the purpose of recording the information in the way explained above.

*Platъ – The sources of Information

The reconstructions undertaken as part of the experiment are based principally on written sources because archaeological finds do not provide clear information. In fact only one possible fragment of *platъ has been found. In 1976, Czech scholar Krystina Marešová published an archaeological find from Uherské Hradiště, a Great Moravian burial in Sady, dated to the 9th AD. The find was a piece of a 3 x 5 cm rusted iron. The rectangle was covered with remains of linen, preserved thanks to the rust. The linen was made of flax and its dimensions are 15 x 15 cm. The flax linen was estimated as the main component of the find, because the iron rectangle was just a small ordinary piece of metal without any ornamentation. Kristýna Marešová interpreted the linen as an example of Slavic “cloth money” (Marešová, 1976, pp.31-32).

The interpretation is however problematic. It can neither be verified nor disputed. Overall, the fact that the question itself cannot be resolved is accepted (Adamczyk, 1999, p.105). We will abandon the archaeological find from Sady-Uherské Hradiště as a possible source of information. Our reconstruction will follow the description in the written sources only.

Source I. - Ibrahim Ibn Yaʻqūb’s 10th century description of the Prague marketplace

The first and the most important source of information about the use of pieces of textile as currency can be found in Ibrahim Ibn Yaʻqūb’s description of the Prague marketplace, as recorded by al-Bakri. The text probably dates to 966 AD:

و يصنع في بلاد بويمه منيدلات خفاف مهلّلة النسج على هيئة الشبكة لا تصلح لشيء وثمنها عندهم في كل زمان عشرة مناديل بقنثار بها يتبايعون ويتعاملون يملكون منها الأوعية وهي عندهم مال وأثمُن الأشياء يبتاع بها الحنطة والدقيق والخيل والذهب والقضّة وجميع الأشياء.

(al-Bakri, Kitāb al-mamālik wal-masālik, p.3)4

Let us abandon the note about coins (qinthār, قنثار) and its ratio to the “small handkerchiefs” and just focus on the description of their physical appearance. The question of how they could be a fixed ratio to the coins (if we are to believe Ibrahim on this point) is not the topic of this article.

For more about the source see Kowalski (1946, pp.21-47). For a discussion on the dating of Ibrahim‘s description see Třeštík (2000, p.55).

Source II. - Helmold of Bosau’s 12th century Chronica Slavorum

The second reference to Slavic cloth currency appears in the 38th chapter of the first book of priest Helmold’s Chronica Slavorum. The text is dated to the second half of the 12th century. The Saxon chronicler wrote about the market habits of the Rans, the Slavic tribe living on the shores of Baltic Sea:

Porro apud Ranos non habetur moneta, nec est in comparandis rebus nummorum consuetudo, sed quicquid in foro mercari volueris, panno lineo comparabis.5 (1.38)

According to Helmold’s description, the Rans only created jewellery or objects used in religious cult from precious metals:

Aurum et argentum, quod forte per rapinas et captiones hominum vel undecumque adepti sunt, aut uxorum suarum cultibus impendut, aut in erarium dei sui conferunt. (1.38)

Victores aurum et argentum in erarium Dei conferunt, cetera inter partiuntur.6 (1.36)

If we are to believe to the chronicler, trade currency only existed in the form of *platъ.

Reconstructing the *platъ

Let us suppose that Ibrahim and Helmold refer to the same practice. The aforementioned connection between *platъ and *platiti appears in all Slavic languages even today. It would therefore appear that the use of a cloth currency was a pan-Slavic practice, which had roots in a common tradition.7

The Slavs probably used the *platъ currency as a tribal custom. The latter was probably gradually replaced by others ways of organizing economic life. The concentration of power, the use of coins and other circumstances pushed the *platъ currency aside. Ibrahim and Helmold therefore both likely recorded the same fading tribal exchange practice, even though their descriptions deal with geographically distant places and with two different time periods (separated by about two hundred years). Now, drawing on the description, let us focus to the question of what the *platъ could look like.

The Material

Helmold’s text contains a reference to flax (panno lineo/ sg. pannus lineus). Ibrahim states that the munaydilāt were “made” or “fabricated” in the lands of Bohemia but he does not specify by whom. His account thus implies (albeit vaguely) that “*platъ production” was a general practice: it was confined neither to a given “producer” nor to an authority reserving the right to individually “issue” it.

Flax was a commonly grown plant, even in early medieval Bohemia, and its processing was probably undertaken in peasant households (Charvát, 1990, p.81). We decided to use flax (Linum usitatissimum), although we know that other materials (esp. wool, hemp and nettle) were also employed in the production of fabrics.

The production mode

No direct evidence exists for how the *platъ was produced. Nevertheless, according to the available information, it seems to have been made in a way typical of the period. There were some attempts to prove that the *platъ was a specially woven fabric, made in a difficult way. The economic value was determined according to the effort put into the production (Pošvář, 1962, p.458). These arguments aimed to explain the economic value of *platъ in the light of the problematic labour theory of value. However, the descriptions in written sources do not support such an interpretation. The hypothesis can therefore also be criticized from the etymological perspective (Piekosiński, 1898, pp.393–394).

Ibrahim informs us about the thin quality of the *platъ material, therefore we have chosen the thread with the thickness measured on average 0.4 mm. In this article, we believe that the *platъ was a loosely woven piece of linen, which is also the predominant interpretation. This one suits both Ibrahim's and Helmold's descriptions and it also suits the linguistic evidence: *poltno (cloth), *platъ (a piece of cloth), *platiti (to pay) (See Figure 1).

In the early Middle Ages the vertical loom was ordinarily used for weaving (See Figure 2).

Following Ibrahim’s mention of a “net-like” appearance, our model of *platъ is woven as a simple plain weave, with thinner thread rotation. It is woven with a single thread in a Z twist both in weft and warp, plain weave with a warp density of 6 threads per 1 cm (See Figure 3).

The final product

The final product was created by dividing the fabric, measuring 40 x 100 cm, into regular squares of 20 x 20 cm. The piece was edged with a simple hem for better strength.

Of course, we are not sure that the *platъ looked like this. Nevertheless the resulting fine linen scarf, woven in the manner of a net, is as close as we could get, with the use of the ancient technology, to the description provided by the written sources (See Figure 4).

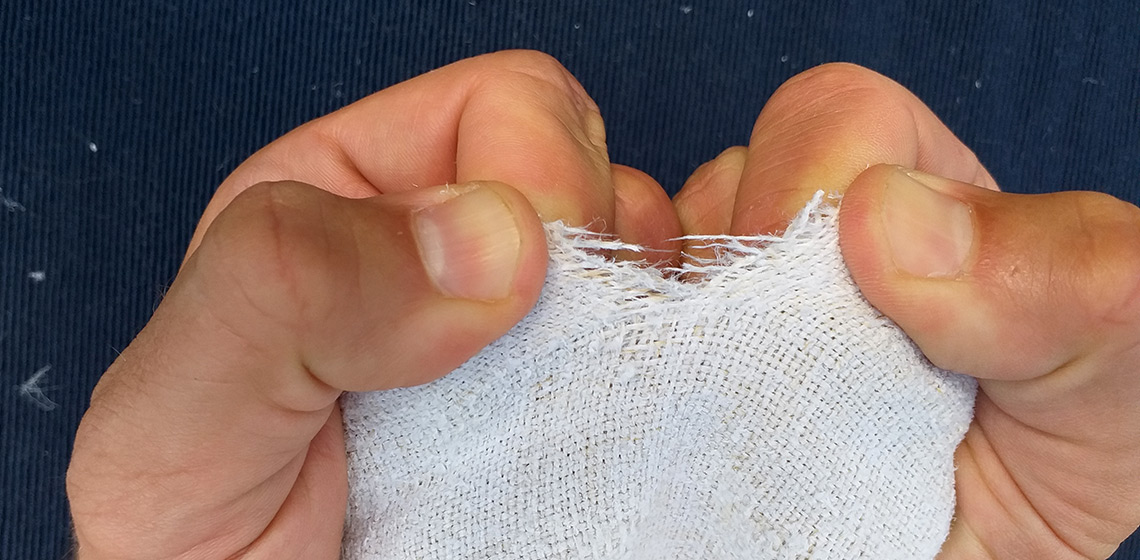

According to our hypothesis, all we have to do is tear the *platъ in two so that both halves can be identified. However, a surprising complication occurred.

The experiment: Details of Fabric used for Recording Commitment

The resulting experimental product - a thin linen “net-like” fabric proved to be too strong to be torn. We did not cut it with a knife or other tool to testify the etymological hypothesis that the *platъ was torn (*tъrgati – “to tear/to rip”; *tъrgъ - “a market”. The Proto-Slavic word for “to cut” was *rězati). Although the meaning of *tъrgati and *rězati was probably very close (Rejzek, 2015, p.584), we decided not to use tools (See Figures 7 and 8).

Although we do not know how skillful the medieval spinners were, it seems that weaving a fabric “of a thin fiber, by way of a net" is very difficult using flax and a horizontal loom. The yarn cannot be thinner, as it is damaged during spinning. These observations therefore lead to two possibilities:

- That the hypothesis about *platъ’s function as a tool for recording a contract is invalid, or at least very complicated. In order to preserve the hypothesis, we would have to suggest that the Slavic spinners invested a lot of time, effort and skill in the production of a fabric designed to be torn. In this case, it could be argued that such efforts were made to support the "sanctity" of the future contract, but this is unconvincing and cannot be proven. Moreover, none of the other objects (symbolon, stipula, tally stick) worked like that. They were made of available material (wood, remnants of old ceramics, reeds) or objects that were not initially designed to break (a ring).

However, the hypothesis does not have to be completely rejected. It is only necessary to find a fine and relatively available “net-like” fabric that could be torn.

- That the textile fabric is a material that becomes brittle: it thins and loses strength over time. The fabric (even linen), be it used for clothing or for other purposes, with time acquires the properties described by Ibrahim.

Since we did not have a worn linen fabric with a similar yarn thickness, we chose a hemp fabric for the next experiment. The piece of hemp cloth shown below has a comparable yarn thickness, it is hand-made unworn fabric. Its fragility and gauze (“net-like”) appearance is caused by the fact that it is almost 80 years old. Hemp was available and used during the period under study, so we will use it (despite Helmold’s report) (See Figure 9).

The material itself is not so important, but it is important to demonstrate the functional principle. We assume that sufficiently old and worn linen would behave similarly. The cloth is fragile enough to be used to demonstrate an act of *tъrgati platъ under the proposed hypothesis (See Figures 10-16).

This procedure demonstrates the possibility of creating mutually identifiable objects from a fabric, which was available in those times.

Conclusion

The archaic Slav currency - in other words pieces of cloth - probably worked on the same principle as other types of archaic contracts created in two identifiable halves. The experiment presented in this paper showed that the pieces of textile fabric used to record mutual commitments were probably not intentionally produced. Ibrahim’s note that the „handkerchiefs“ or „cloths“ were „fabricated“ could then be read as a mere stylistic expression of the fact that they were widely circulated (and thus probably produced somewhere).8

They were just ordinary textiles (maybe very old clothes), which started to lose their original function. The fabric was relatively valuable and the dress was certainly inherited as well. However, sometimes the fabric wore down and became “very fine and net-like”. It was probably then torn and used to create a contract of mutual obligations.

The contracts recorded with the help of tearing old and used textiles could have gained even more respect if associated with a kind of contact magic. The debtor would thus be highly motivated to fulfill his commitment and re-acquire “the pledge” – the piece of cloth torn from a linen (or other) coat that he (or his wife, or father...) wore for a long time. The development of this idea may be a topic for further studies in cultural anthropology or ethnography.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kristýna Urbanová for the flax net-like fabric creation and for the photo-documentation of the process. See http://jakoblecipracloveka.cz/

- 1The Slavic suffix -ati is added to make a verb in infinitive form (*tъrgъ = “a tear, a rip”, but also “a market”; *tъrgati = “to tear, to rip”). A black yer ъ is disappearing.

- 2Transl: Each of us humans is a symbolon

- 3Transl.: Stipulatio is giving or receiving a promise, which is why the participants in this act are called “promising” or “guarantors”. The word stipulatio is derived from the expression for reed (stalk). Because when the ancestors promised each other something, they confirmed the agreement by breaking a reed that they held in their hands. By joining the pieces of reed, they recalled the promises they had made (or because, according to Paul the lawyer, the word stipulus used to have “a firm” meaning).

- 4Transl.: In the land of Bohemia (būyeme, compare to Kowalski, 1946, p.49), small, light handkerchiefs are made of a thin fiber, in the manner of a net. They are of no use, and their price is equal to ten handkerchiefs for qinthār (i.e. qīrāṭ, see Kowalski, 1946, p.49) among them (Slavs) at any time. Through (or with) them they trade and make transactions with each other. They possess containers full of them and they are the most precious of all items (athmanu al-ashyāʼ; alternatively „they are the price of all things for them“, athmunu al-ashyāʼ; depending on the vocalization, (see Kowalski, 1946, p.49). With it, one can buy corn [wheat or rye], and flour, and horses, and gold, and silver, and all things.

- 5Transl.: Further, Rans do not own coins, nor do they have a habit to buy things for coins, but whatever you wish in marketplace, you will buy for flax cloth.

- 6Transl.: Gold and silver, which they obtain from theft or kidnapping or otherwise, they use for gracing their wives or they deposite it in the treasury of their god. When they win (Rans), they deposite gold and silver in the tresury of God, the rest they redistribute among themselves

- 7For the discussion see Adamczyk, 1999, pp.95, 119-123.

- 8Ibrahim‘s brief and vague report allows for little more than conjectures and speculations. The fact that the 10th century Arab merchant who made transactions with the local nobility and payed in his account a certain deal of attention to the local power relations does not tie the munaydilāt to a given authority diminishes the possibility that their production was somehow controlled or centralized.

Country

- Czech Republic

- Poland

- Slovakia

Bibliography

Adamczyk, J., 1999. Raz jeszcze o płacidłach płóciennych. Mazowieckie Studia Humanistyczne, 5(1), pp.93–124.

al-Bakri. Kitāb al-mamālik wal-masālik. Kowalski, T., ed. 1946. In: T. Kowalski, ed. Relacja Ibrāhīma ibn Ja‛kūba z podróży do krajów słowiańskich w przekazie Al-Bekrīego. [online] Kraków: Gebethner I Wolff. Available at: < https://sources.cms.flu.cas.cz/src/index.php?s=v&cat=52&bookid=1065 > [Accessed 30 March 2020].

Charvát, P., 1990. Pallium sibi nullatenus deponatur: textilní výroba v raně středověkých Čechách. Archeologia historica, 15(1), pp.69–86.

ESJS, 2012. Etymologický slovník jazyka staroslověnského. 16, ѕьde - trътъ. Brno: Tribun EU.

Henkelman, W.F.M. and Folmer, M. L., 2016. Your tally is full! On wooden credit records in and after the Achaemenid Empire In: K. Kleber and R. Pirngruber, eds. Silver, money and credit, a tribute to Robartus J. van der Spek on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. pp.133-239.

Hopper, R.J. and Millet, P.C., 2016. Oxford Classical Dictionary. [online] Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: < https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0… > [Accessed 26 June 2020].

Helmold. Chronica Slavorum. Schmeidler, B., ed. 1937. Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi 32: Helmolds Slavenchronik (Helmoldi presbyteri Bozoviensis Cronica Slavorum). Hannover: Hahn.

Isidore of Seville, Saint. Etymologiae V. 2003. Translated by L. Blechová. Praha: OIKOYMENH.

Jakimowicz, R., 1948. Kilka uwag nad relacją o Słowianach Ibrahima ibn Jakuba. Slavia Antiqua, 1, pp.439–459.

Kowalski, T., 1946. Relacja Ibrāhīma ibn Ja‛kūba z podróży do krajów słowiańskich w przekazie Al-Bekrīego. [online] Kraków: Gebethner I Wolff. Available at: < https://sources.cms.flu.cas.cz/src/index.php?s=v&cat=52&bookid=1065 > [Accessed 30 March 2020].

Kratochvil, J., 2020. O trhání a trhu: Úvěrová teorie společenské monetizace jako výkladové schéma etymologické souvislosti mezi trháním a pojmenováním směny. Naše řeč, 103(3), pp.212-230.

Marešová, K., 1976. Nález předmincovního platidla na slovanském pohřebišti v Uherském Hradišti-Sadech. Časopis Moravského muzea – vědy společenské, 61(2), pp.31–36.

Mauss, M., 1999. Esej o daru, podobě a důvodech směny v archaických společnostech. Translated by J. Našinec. KLAS: klasická sociologická tradice 4. Praha: Sociologické nakladatelství.

Piekosinski, F., 1898. Moneta polska w dobie piastowskiej: I., Zawiązki rzeczy menniczej w Polsce wieków średnich. [online] Krakow: Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Available at: < https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/show-content/publication/edition/10456?id=10456 > [Accessed 30 March 2020].

Plato. Symposium. Lamb, W.R.M., ed. 1925. Loeb Classical Library 166. [online] Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univerzity Press. Available at: < https://www.loebclassics.com/view/plato_philosopher-symposium/1925/pb_LCL166.141.xml > [Accessed 28 June 2020].

Pošvář, J., 1962. Plátno jako platidlo u Slovanů. Slavia, 31(3), pp. 456–459.

Rejzek, J., 2015. Český etymologický slovník. 3rd ed. Praha: Leda.

Shell, M., 1989. The ring of Gyges. Mississippi Review, 17(1-2), pp. 21-84.

Třeštík, D., 2000. Veliké město Slovanů jménem Praha". Státy a otroci ve střední Evropě v 10. století. In: L. Polanský, J. Sláma and D. Třeštík, eds. Přemyslovský stát kolem roku 1000: na paměť knížete Boleslava II. (+ 7. února 999). Praha: NLN, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny. pp. 49-70.

Vasmer, M., 1987. Etimologičeskij slovar‘ russkogo jazyka: V četyrech tomach. 4, T-Jascur. Moskva: Progress.