The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Observations on Italian Bronze Age Sword Production: The Archaeological Record and Experimental Archaeology

In spite of the very large quantity of Bronze Age swords in Northern Italy, only a few stone moulds have been found. Tests have shown that carving such big stone moulds (more than 60 cm long) requires a large amount of raw material, deep knowledge and skill, rather than a wide set of implements. It has also been shown experimentally that the long sandstone sword moulds, especially in regards to blade details, are affected by the fragility of the material, when the stone comes in contact with the flowing melted bronze. These reasons could mean that the moulds were made with other materials and through other techniques that have not left a visible (or identified?) trace on metallurgical sites, as other authors have already suggested (cfr. Ottaway and Wang 2004). A team of archaeologists and craftspeople is now working on sand casting method.

Introduction

The general characteristics of the casting technique, which was used in northern Italy in the Bronze Age, have long been investigated, due to the great amount of moulds discovered over more than 150 years of archaeological research. A major contribution to this knowledge derives from the extraordinary discoveries of the manufacturing area in the villages of Montale (MO) (Cardarelli, 2004), Beneceto Fornace del Gallo (PR) (Bernabò Brea et al., 2008, 87-111) and Castellaro del Vhò (CR) (Cierny, et al., 2001). These three discoveries document how the high temperature required for alloy fusion was reached in a pit dug in the ground which, in some cases, was coated with a sandy, clay plaster (Binggeli, et al., 1997, 567-569; Cavazzuti et al., forthcoming). The numerous findings of nozzles and baked clay blowing pipes and tuyères prove that the fire lighted in the pit was fed by air blowing on embers. The point of the pit where the higher temperature was reached was directly above the blowing tuyère. It was there the crucible (a refractory ceramic receptacle containing the two metals) was inserted.

When the alloy was melted into a liquid, it was poured into moulds; a very large quantity of these moulds discovered in Middle Bronze Age archaeological context are made of stone, although there are also some made in ceramic.

Archaeological approach: the study of currently available materials

Therefore, the general frame of Bronze Age metalworking is now well known; nevertheless, there are some aspects that still remain unclear and that archaeological materials and recent studies are not able to verify. One of these aspects concerns the production of a particular type of object that was very important for its functional and economic value, as well as for its symbolic meaning, the sword.

The archaeological contexts where this particular category of metal objects are discovered indicates the ideological importance it assumed during the Bronze Age. In the Italian Peninsula there are plenty of swords recovered from ancient riverbeds or lakes, as well as from summits or mountain passes, and they can be interpreted as special offerings to the gods (Bettelli, 1997, 726). Other areas where artefacts are recovered are burial-places, both inhumations, as in the case of Olmo di Nogara necropolis (Salzani, 2005) where 43 swords were recovered (with about half of the total of Italian swords recovered dating back to the Bronze Age) and cremation, as in the case of Casinalbo necropolis (MO), where weapons such as swords and daggers were not inserted in the urn as grave goods but were deprived of their function, broken into pieces and scattered around specific areas of the necropolis (Cardarelli, et al., 2006, 624-642; Cardarelli et al. forthcoming).

Some sword types, albeit more uncommon, were also recovered in settlements, as in the case of a simple base sword (which might be of the Bigarello type) discovered in Gaggio, a terramara village dating back to the early phases of the Middle Bronze Age (Balista, et al., 2008).

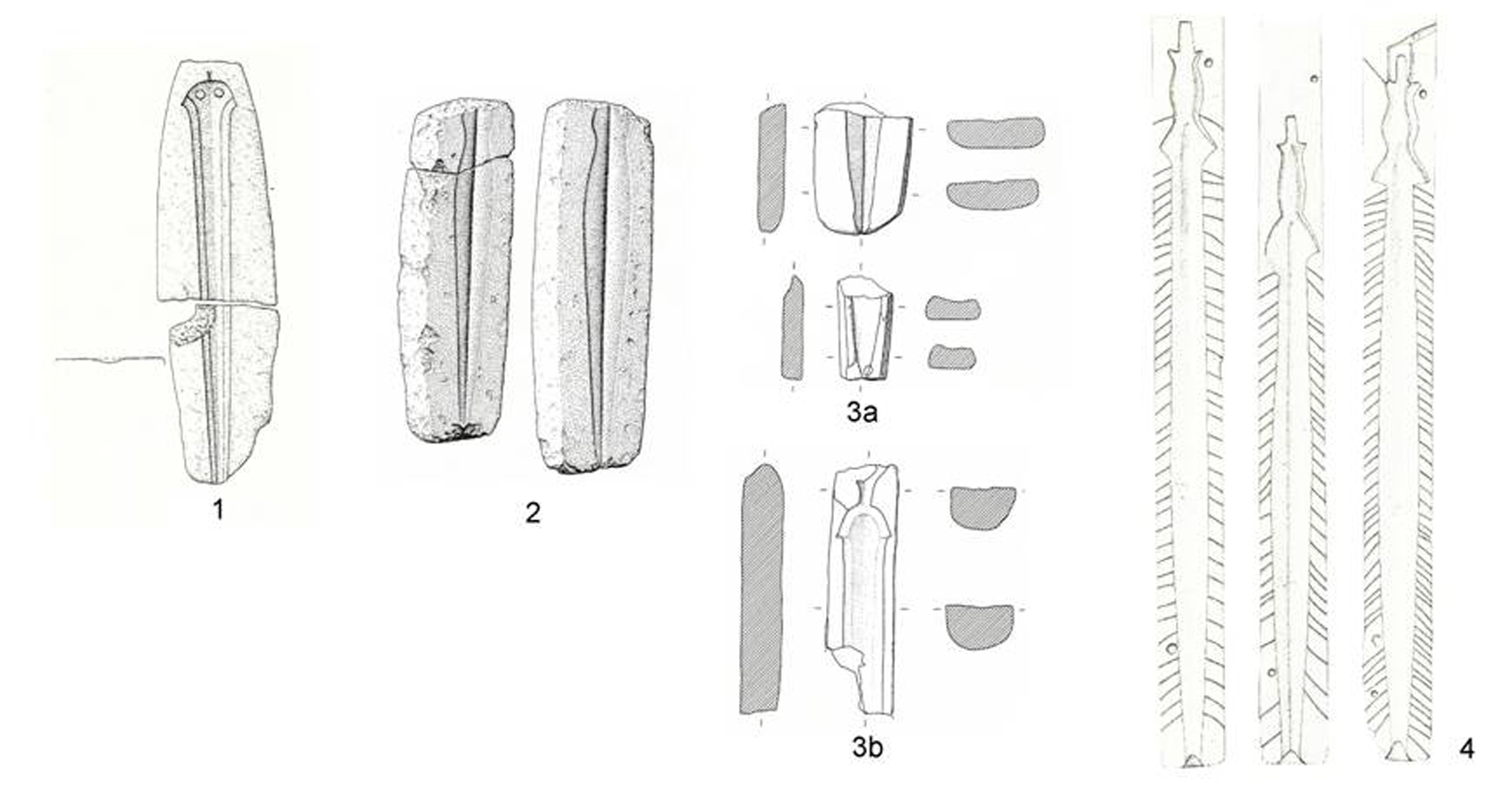

Taking all this data into account and considering the different origins of the artefacts, it is clear that the swords recovered in the Northern Italy area, dating back to the Bronze Age, are numerous (See Figure 1). A comparison between this element and the number of sword moulds dating back to the Bronze Age shows a high imbalance, therefore there are only five matrices required for the production of this particular weapon in Italy (See Figure 2-3):

- a sandstone sword mould (Roncoferraro type) from Castione Marchesi terramara (PR) dating back to the Middle Bronze Age 1-2 (1650-1450 BC circa);

- a calcarenite sword/rapier mould (Pieve San Giacomo type) from Coriano archaeological area (RN), dating back to the Middle Bronze Age 2 (1550-1450 BC circa);

- a calcarenite sword mould (unknown type) from Castellaro del Vhò (CR), dating back to the Middle Bronze Age 2 (1550-1450 BC circa);

- a ceramic sword mould (unknown type) from Castellaro del Vhò (CR), dating back to Middle Bronze Age 2 (1550-1450 BC circa);

- a three chiselled faces of the same soapstone mould for a grip-tongue sword (Erbenheim type) from Piverone settlement (TO), dating back to the Final Bronze Age (1150-950 BC circa).

Fig 3. Sword mould from Northern Italy: 1. Castione Marchesi (PR), sandstone mould (Roncoferraro type), Middle Bronze Age 1-2 (Bianco Peroni, 1970, table 2); 2. Coriano (RN), calcarenite mould (Pieve San Giacomo type), Middle Bronze Age 2 (Bianco Peroni, 1994, table 42); 3. Castellaro del Vho (CR), calcarenite moulds (3a) and ceramic mould (3b), Middle Bronze Age 2 (Cierny et alii, 2001, p.76); 4. Piverone (TO), three chiseled faces of the same soapstone mould for a grip-tongue sword (Erbenheim type), Final Bronze Age (Bianco Peroni, 1970, table 75).

Experimental archaeology activity

Through research activities (Barbieri and Lugli, 2012) and experimental archaeology it has been possible to create some replications of moulds for swords production, using a type of stone similar to those used to create the majority of moulds recovered in the Bronze Age villages set in the Modena area and that can be traced locally (Barbieri and Cavazzuti, forthcoming). Further, these moulds have been used during experimental bronze-casting activities aimed at testing their resistance. It resulted that, due to repeated castings of molten bronze in the moulds, when the metal temperature exceeds 1300 °C, the negative of the object carved in the stone tends to lose its details because of the fragility of the material, especially on the edge of the blade. Another remarkable aspect is the deformation undergone by the stone, which occurs in the exact moment when it comes in contact with the molten metal. The two half shells tend to sag and they do not fit together, which is essential for succeeding in the casting process, so that continuous maintenance is needed (See Figure 4a-c).

The archaeological record leads to the hypothesis that, in the Bronze Age, swords were mainly cast through an alternative technology that required the use of a material that didn't leave a trace on metallurgical sites. Among the likely possibilities, the focus has been on sand casting using two wooden clamps and calcareous fine sand (See Figure 5a-f).

Conclusion

The shortage of findings of sword stone moulds in comparison to the very large quantity of Bronze Age swords coming from Northern Italy suggests that different techniques and a different kind of material were used. Sand moulds are a viable alternative because it is easier to source the raw material, less work is needed to make the mould and better detail can be obtained so that less work is needed to finish the final product.

Country

- Italy

Bibliography

BALISTA, C., BONDAVALLI, F., CARDARELLI, A., LABATE, D., MAZZONI, C. and STEFFÈ G., 2008. Dati preliminari sullo scavo della Terramara di Gaggio di Castelfranco Emilia (Modena): scavi 2001-2004. In: Bernabò Brea M., Valloni R., ed. 2008. Archeologia ad alta velocità in Emilia. Indagini archeologiche lungo il tracciato ferroviario. Quaderni di Archeologia dell’Emilia Romagna, 22, pp.113-138

BARBIERI, M. and LUGLI, S., 2012. Forme di fusione dalle terramare del territorio modenese e reggiano: caratterizzazione dei litotipi e individuazione delle provenienze, in Atti del VII Convegno Nazionale di Archeometria, Modena.

BARBIERI, M., CAVAZZUTI, C., (in press). Stone moulds from Terramare (Northern Italy): analytical approach and experimental reproduction. Proceeding from the 7th U.K. Experimental Archaeology Conference. Cardiff, 11-12 January 2013.

BINGGELI, M., BINGGELI, M., BOSCHETTI, A. and MÜLLER, F., 1997. Una dimostrazione di archeologia sperimentale: la fusione di oggetti in bronzo. In: M. Bernabò Brea, A. Cardarelli and M. Cremaschi, ed. 1997. Le Terramare. La più antica civiltà Padana. Milano: Electa. pp.567-569.

BERNABÒ BREA, M., CARDARELLI, A. and CREMASCHI, M. ed., 1997. Le Terramare. La più antica civiltà Padana. Milano: Electa.

BERNABÒ BREA, M., MIARI, M., BIANCHI, P.E., BRONZONI, L., FERRARI, P., GUARISCO, F., LARI, E., LINCETTO, S., MAGGIONI, S., OCCHI, S. and SASSI, B., 2008. La Terramara di Forno del Gallo a Beneceto (Parma). In: M. Bernabò Brea and R. Valloni, ed 2008. Archeologia ad alta velocità in Emilia: indagini geologiche e archeologia lungo il tracciato ferroviario. Borgo S. Lorenzo: All’insegna del Giglio. pp.87-111.

BETTELLI, M., 1997. Materiali relativi al rito e al culto. Spade da vette e da fiumi. In: M. Bernabò Brea, A. Cardarelli and M. Cremaschi, ed. 1997. Le Terramare. La più antica civiltà Padana. Milano: Electa. p.726.

BIANCO PERONI, V. ed., 1970. Le spade nell’Italia continentale.Munchen: C.H. Beck.

BIANCO PERONI, V. ed., 1972. I pugnali dell’Italia continentale. Suttgart: F. Steiner.

CARANCINI, G.L., 1992. La metallurgia e gli altri rami dell’artigianato: organizzazione, stile e tecniche della produzione e modi di circolazione dei manufatti – L’Italia centro-meridionale. In: Congresso l’età del bronzo in Italia nei secoli dal XVI al XIV a.C.: Viareggio 26-30 ottobre 1989. Firenze: All’insegna del Giglio. pp.235-254.

CARANCINI, G.L., 1997. La produzione metallurgica delle terramare nel quadro dell’Italia protostorica. In: M. Bernabò Brea, A. Cardarelli and M. Cremaschi, ed. 1997. Le Terramare. La più antica civiltà Padana. Milano: Electa. pp.379-389.

CARDARELLI, A. ed., 2004. Guida al Parco archeologico e Museo all’aperto della Terramara di Montale. Modena: Comune, Museo civico archeologico etnologico.

CARDARELLI, A., CREMASCHI, M., CATTANI, M., LABATE, D. and STEFFÈ, G., 1997. Nuove ricerche nella terramara di Montale (MO). Primi risultati. In: M. Bernabò Brea, A. Cardarelli and M. Cremaschi, ed. 1997. Le Terramare. La più antica civiltà Padana. Milano: Electa. pp.224-228.

CARDARELLI, A., LABATE, D. and PELLACANI, G., 2006. Oltre la sepoltura. Testimonianze rituali ed evidenze sociali dalla superficie d’uso della necropoli della terramara di Casinalbo (MO). In: Studi di protostoria in onore di Renato Peroni. Borgo S. Lorenzo: All’insegna del Giglio. pp.624-642.

CARDARELLI, A., CAVAZZUTI, C., PELLACANI, G. and SALVADEI, L., forthcoming. Manipolazione e frammentazione rituale nelle necropoli ad incinerazione dell'età del bronzo in Italia settentrionale: l'evidenza di Casinalbo. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Choice Pieces. The destruction and then manipulation of goods in the Later Bronze Age: from reuse to sacrifice”, Roma 16-18 febbraio 2012.

CAVAZZUTI, C., PELLEGRINI, L., SCACCHETTI, F. and ZANNINI, P., (in press). Tracce di fosse di fusione dalle terramare: ci siamo persi qualcosa?. In: Atti della XLV Riunione Scientifica I.I.P.P., 26-30 ottobre 2010, Modena.

CIERNY, J., DEGASPERI, N., FRONTINI, P. and PRANGE, M., 2001. Le attività metallurgiche. In: P. Frontini, ed. 2001. Castellaro del Vho. Campagne di scavo 1996-1999. Scavi delle Civiche Raccolte Archeologiche di Milano. Como: New press. pp.58-77.

CIERNY, J., DEGASPERI, N. and FRONTINI, P., 2001. Castellaro del Vhò di Piadena (Cremona): strutture fusorie a cielo aperto del Bronzo Medio. In: A. Giumlia-Mair, ed. 2002. I bronzi antichi: produzione e tecnologia : atti del 15. Congresso internazionale sui bronzi antichi, organizzato dall'Università di Udine, sede di Gorizia, Grado-Aquileia, 22-26 maggio 2001.Montagnac: Mergoil.

GIARDINO, C., 1998. I metalli nel mondo antico. Introduzione all’archeometallurgia. Bari: Laterza.

OTTAWAY, B.S. and SEIBEL, S., 1998. Dust in the wind: experimental casting of bronze in sand moulds. In: Paléométallurgie des cuivres : actes du Colloque de Bourg-en-Bresse et Beaune, 17-18 octobre 1997 / sous la direction de M.-Ch. Frère-Sautot ; préface de J.-P. Millotte. Montagnac: Mergoil.

OTTAWAY, B.S. and WANG, Q., 2004. Casting Experiments and Microstructure of Archaeologically Relevant Bronzes. British Archaeological Records, International Series, 1331.

SALZANI, L., 2005. La necropoli dell’età del Bronzo all’Olmo di Nogara. Verona: Comune.