The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Towards a Best Practise of Volunteer Use Within Archaeological Open-air Museums: an Overview with Recommendations for Future Sustainability and Growth

For many archaeological open-air museums (AOAMs), volunteers are an essential and highly visible component of an effective institution. Volunteers bring museums to life with meaningful interpretive contacts, and offer institutions the opportunity to broaden their mission and complete tasks that may not otherwise be possible. Current trends in heritage institutions predict ever-shrinking budgets, and with extra demands on staff, it is likely that museums will depend more and more on volunteers. Indeed, many museums already depend on them just to keep the lights on, while others are completely staffed by volunteers. As such, volunteers are essential for the long-term sustainability of these organisations. The goal of this study is to report how volunteers are currently used within archaeological open-air museums, and to continue the discussion with regard to best practises for volunteer management.

Volunteers are a critical resource in the sustainability of museums (including AOAMs) and are a vital and underserved audience (Goodlad and McIvor, 2012). In the museum context a volunteer is one who offers their knowledge and service without compensation with the aim of benefitting others, as well as contributing to the general wellbeing of society (Gibbs and Sani, 2009). Volunteer work can be regular or occasional, full-time or part-time (Csordas, 2011). Within Europe patterns of volunteerism (Benevolat/Ehrenamt) are diverse. Countries such as Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom have very high levels of participation at over 40%, Denmark and Germany have high levels of participation, between 30-39%. There is a more standard participation in France and Latvia, with between 20-29% and a relatively low participation in Belgium, Ireland, Spain and the Czech Republic at around 10-19%. The lowest participation levels are in Italy, with figures below 10% (Angermann and Sittermann, 2010).

In the UK alone an estimated 100,000 volunteers contribute over £108 million in value per year (Hill, 2008). Because of industry-wide fiscal pressures most museums turn to volunteers in some capacity: financial constraints cannot provide for a fully staffed institution (Ambrose and Paine, 2012). As such, volunteers are essential for the long-term sustainability of these organisations.

This study will investigate how and to what extent volunteers are currently deployed within the heritage sector defined as archaeological open-air museums (AOAMs). Additionally, the author will draw conclusions regarding the future priorities and concerns of volunteer use within AOAMs and the implications for the sustainability of this type of museum.

To address these goals, a modified version of the volunteer survey created by the Institute for Volunteering Research is used (Chambers, 2002). There is a keen awareness that this is an introductory study with significant limitations. The number of questions were necessarily limited and the online nature of the survey hindered further questions based on specific responses. This type of museum presents unique opportunities for volunteer study and the author hopes that a follow-up study will be possible.

Geographical distribution of responses

A total of 65 email questionnaires were sent to self-identified archaeological open-air museums (AOAMs). The AOAMs were identified using online research with guidance from Dr. Roeland Paardekooper (personal communication, 2014). All the respondents were members of EXARC (EXARC.net), the ICOM affiliated organisation representing archaeological open-air museums.The results of this survey are based on the information provided by 32 completed questionnaires which constituted a 50% response rate. The author invited all the respondents to (optionally) self-identify: out of 32 respondents, five chose to remain anonymous. The respondents represented 14 European countries. The most heavily represented countries were the United Kingdom (25%) and Germany (19%). The majority of responses (72%) came from the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and Italy. Other represented countries included: Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Netherlands, Spain, and Ukraine (each with one response).

Completed surveys were received from:

- Ancient Technology Centre

- Archaeological-Ecological Centre Albersdorf

- Bauspielplatz Roter Hahn e.V.

- Boyne Currach Heritage group

- Butser Ancient Farm

- Celtic Harmony

- Center of Living History "Oleshye"

- Curia Vítkov

- Eindhoven Museum

- Fördererkreis Museumsdorf Düppel e. V.

- Fotevikens Museum

- Fundació Castell de Calafell

- Gallische Hoeve

- History Matters

- Landa Park As

- Lofotr Viking Museum

- Matrica Museum and Archaeological Park

- Oerlinghausen

- Parco Archeologico del Forcello

- Parco Archeologico didattico del Livelet

- Pfahlbaumuseum Unteruhldingen

- Sagnlandet Lejre

- Somerset County Council Heritage Service

- Storholmen AOAM

- The Scottish Crannog Centre

- Veien Cultural Heritage Park

- Wikinger Museum

Demographics

According to this research, over 90% of responding museums involved volunteers. This data is in line with other general surveys of volunteer use in museums (Gibbs and Sani, 2009). Because of industry-wide economic pressures, most museums turn to volunteers in some capacity: fiscal constraints cannot provide for a fully staffed institution (Ambrose and Paine, 2012). Moreover, 17% (5) of the institutions are totally volunteer run including vzw Gallische Hoeve, History Matters, Centre of Living History "Oleshye", Curia Vítkov and Fördererkreis Museumsdorf Düppel e. V. A majority of institutions (55%) utilise1-20 volunteers (See Figure 1).

Fig 1. How many volunteers does your museum use? (Source: Author).

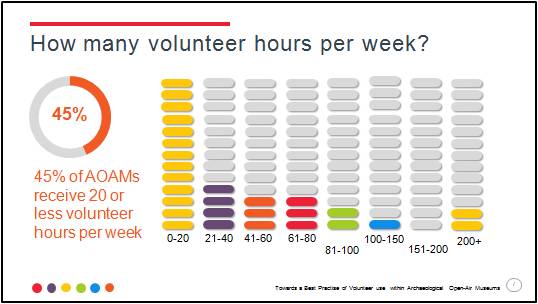

Only one institution has 81-100 volunteers while 4 AOAMs have over 100 volunteers (14%) including Eindhoven and Butser Ancient Farm. The author investigated the gender profile of volunteers using simple averages—each responding institution has the same weight whether they have 1 or 100 volunteers. 43% of respondent indicated a 50/50 gender balance. The author asked the institutions to provide a total weekly figure for their volunteers. As a whole each institution receives between 31-54 hours of volunteer help per week. Some 45% of AOAMs receive 1-20 hours service per week and 10% of institutions received either 21-40 or 61-80 hours of service per week. Two institutions (7%) receive over 200 volunteer hours per week (Sagnlandet Lejre and Anonymous 004 UK).

Fig 2. How many volunteer hours do your volunteers give to your museum?

Volunteers provide an average of 40 hours of service per week (See Figure 2): this is the equivalent of at least 1 FTE per site. Two respondents receive over 200 volunteer hours per week (Sagnlandet Lejre and Anonymous 004 UK). The majority of AOAMs manage between 1 - 20 volunteers although four museums use over 100 volunteers, namely, Eindhoven, Butser Ancient Farm and two anonymous respondents (both in the UK). The deployment of volunteers allows these institutions to perform work that they would not otherwise be able to accomplish. This includes extending public hours (David de Clercq, personal communication, 2014), more interpretive personnel (Gunter Schobel, personal communication, 2014) and fundraising (Clare Holt, personal communication, 2014). Within the sample group volunteering is not often used as a path to employment nor is it used to increase diversity. The gender of AOAM volunteers is generally 50% female and 50% male (43% respondents). Although many museums utilise teenage volunteers, most do not offer a separate program based on age.

Generally speaking, volunteers within the heritage sector are typically older, retired individuals. The event of retirement was found to have a significant impact on this age-groups’ decision to volunteer. Most previous research has indicated that the average age of general museum volunteers is about 55. This body of research suggests AOAM volunteers are typically younger with an average age around 30 (See Figure 3).

Fig 3. What is the % of volunteers within the following age groups?

Why should this be? One can speculate that strong connections within university-based experimental archaeology programs encourage college-age volunteers, while the active and social nature of participation is attractive to younger people.

Of the AOAMS that do not involve volunteers, the major reason was ‘Too time consuming’ (33.3%). One response indicated health and safety concerns and another stated: ‘We cannot expect a volunteer to act like an adequately paid professional employee/freelance.’ Other issues that were preventing the institutions from involving volunteers included “Don’t have enough time’ (33.3%) and ‘Lack of specific volunteer manager’ (22.2%). No respondents selected ‘Resistance from paid staff’ and only one response identified ‘Worried about job substitution issues’.While volunteer management can be very time consuming the investment of time can be an effective and efficient use of limited resources (Connors, 2011).

Why do you work with volunteers?

The respondents ranked ‘It allows us to do things we could not normally do’ as the most important reason for involving volunteers (27.5%). Other responses included: ‘It saves money’ (20%), ‘It promotes community involvement’ (19%), and ‘It gives our work added value’ (15%). ‘It increases diversity’ (9%) and ‘To give people a route to employment’ (6%) were least frequently selected answers. These results closely mirror the results from the IVS survey of museums in England with ‘diversity’ ranking lowest of mandatory questions. The optional response of ‘To give people a route to employment’ scored lowest overall at 6% in the author’s study.

What do volunteers actually do?

The author requested that institutions check all tasks that volunteers perform. This resulted in 117 responses. Given a response rate of 29 institutions which use volunteers, this finding suggests that volunteers are engaged in an average of 4 identified tasks per institution. The following tasks all demonstrated a 10%-13% positive response:

- Guiding / Interpretation (12.5%)

- Presentation of Traditional Crafts (11.9%)

- Information / Communication (11.3%)

- Display / Exhibition (10.6%)

- Building Reconstruction (10%)

Some of the institutions use volunteers in fundraising (6.3%) and the remaining tasks all scored in the 3%-5% range: Archives (4.4%), Administration (3.8), Management (3.1%), Committee Work (3.1%), and Library Work (1.9%). Additional comments indicated other typical tasks included maintenance, gardens and collection management.

In general volunteers provide two types of work: interpretation and service. While both are essential, interpretive work is much more visible as it includes all forms of information presentation including costumed and non-costumed narratives, first and third-person interpretation, tour guide duties, and the presentation of traditional crafts.

Interpretation is highly person-intensive but is essential for today’s visitor. Because of the public’s expectations, static displays are insufficient to engage, educate and entertain the visitor. The time involved in recruiting and training volunteers—specifically first person costumed interpreters—is substantial, and it make sense to protect and nurture that investment through the wise use of volunteer best practices. Institutions invest a lot more time into these interpreters making it even more essential to retain experienced volunteers.

Service work is equally important as it accomplishes a range of tasks that may otherwise remain undone. As well as support work, a large number of volunteers are actively involved in the creation and reconstruction of buildings, exhibits and environments—elements that are critical to the success of most AOAMs. When asked, 75% of respondents stated that using volunteers allowed the institution to complete projects that could not otherwise be done. The use of volunteers also saved money and promoted community involvement. Utilizing volunteers facilitates the growth of institutions: looking at this list, think about how many of these types of things you could accomplish but are unable to because of limited staff. Above and beyond these specific activities, volunteers support a number of critical functions that can enhance sustainability and provide a direct link to visitors. For example, 20 interpretive volunteers can observe and monitor a great deal of visitor feedback, and this can be relayed to management to affect positive change. Moreover, volunteers can also advocate for the institution: happy volunteers can tell your story and encourage others to visit and indeed volunteer. Of course the reverse can also be true: disgruntled volunteers can quickly damage the reputation of the institution. While volunteers contribute a great deal, it is essential that the museum provides a safe and nurturing environment in which volunteers feel comfortable and needed. A well-organisedvolunteer program provides the structure that ensures volunteers can be as effective and happy as possible.

One of the most pressing questions, then, must be how volunteer programs can be developed, along with increased volunteer commitment to contribute to the sustainability of institutions. There are few basic concepts of volunteer management that constitute best practice within the heritage sector which include:

- Having an identified staff person responsible for volunteers

- Using active and fair recruitment practices

- Providing ongoing training

- Providing appropriate rewards

- Providing regular evaluation

Managing volunteers

While the majority of AOAMs have a specific individual responsible for volunteers (70%) there are a sizable majority that do not (30%). Job titles that are specifically tasked with volunteer responsibilities include: Coordinator for Volunteers, Volunteer Manager, Volunteer officer, and Volunteer project officer.Other employees and/or job titles with volunteer responsibilities include: Head of Educational Services, Farm Program manager, Museum director, PR (2), Manager, Managing Director, and Secretary.

The appointment of a volunteer manager is vital to the long term success of most volunteer programs (McCurley, Lynch, and Vesuvio, 1989). This study shows that 30% of AOAMs do not have a single dedicated individual responsible for volunteers. With the multitude of demands on all members of staff there is a danger that the priority of the volunteer program is diminished. This can result in negative effects on volunteer commitment and morale. A number of institutions are aware of the need for a dedicated volunteer coordinator including Archaeological-Ecological Centre Albersdorf (Rüdiger Kelm, personal communication, 2014) and History Matters (Gary Ball, personal communication, 2014).

Recruiting volunteers

According to this documented research, the two most popular methods of recruiting are: ‘Word of mouth’ and ‘volunteers approach us’. Secondary approaches include ‘Friends groups’, ‘Links with educational establishments’, ‘Intermediary organisations’. Advertising, both within the organization and in the press, scored significantly lower. Additional methods focused on social media (specifically Facebook and Twitter). The author’s findings reflect the IVR survey of UK museum volunteers (Chambers, 2002).

A slight majority of respondents indicated that they did not have enough volunteers to allow them to do what they wanted to do (53.6%). This finding reflects a common thread in a range of museums (Howlett, Machin, and Malmersjo, 2005).

While 19.5% of respondents thought it was becoming ‘Much easier’ or ‘Easier’ to recruit volunteers and 12.2% of respondents indicated that it was becoming ‘Much harder’ or ‘harder’. A majority of respondents (41.5%) indicated ‘Neither easier nor harder’. while 11 respondents chose the ‘Other’ category. The additional comments that supported easier recruitment included:

- “Our organisation is becoming more well-known”,

- “We have appointed a volunteer manager and this makes the volunteer experience much better”,

- “Our open-air museum is an exceptional working place”, and

- having “…the resources to allow volunteer participation”.

Additional comments that support a more challenging recruitment environment included:

- “Volunteers from the community are non-existent. We are in a small rural area and the kind of people who volunteer are already saturated or over committed. Student placements are regular but this is an expensive tourist area so finding them affordable accommodation is a problem”;

- “More people need to make commitments to jobs and families, leaving less time for volunteer work”; and,

- “It’s easier to get foreign volunteers then it is to get from our own country”.

These findings, with regard to volunteer recruitment, reflect both the IVR findings (Howlett, Machin, and Malmersjo, 2005)and generally accepted patterns of volunteer recruitment (Sandell and Janes, 2007). While ‘word of mouth’ and ‘friends groups’ are valuable recruitment tools, alternative, slightly less effective marketing strategies can be useful in attracting new sources of volunteers. The culture of volunteering differs according to the country - some countries have long traditions of volunteering while some cultures are more skeptical (Angermann and Sittermann, 2010). One respondent notes: “It’s easier to get foreign volunteers then it is to get from our own country”. Additionally, many of the AOAMs in this study are in less-populated, rural areas where volunteers are harder to acquire.However, a museum recruits volunteers, it is recommended that a variety of methods are employed to recruit volunteers. Recruitment is essential even with a full quotient of the ‘right’ volunteers, as even the best will move on to other projects or other commitments.

Training volunteers

Seven out of ten organisations (69%) provide orientation / induction for their volunteers.

Training is provided for volunteers in 80% of organisations.

Identified areas of training include:

- Orientation, learning handicraft and other things about the Viking age

- Ongoing skills training, safety training, and customer service training

- They support the archaeologist during their activities in the Park

- Health and safety, use of tools, and site information

- Workshops and seminars in autumn/winter

- Ancient crafts; ancient construction methods

- Woodworking

- Health and safety, equipment handling, risk assessment, heritage interpretation, crafts and traditional skills.

The majority of archaeological open-air museums in this study do provide orientation and training for volunteers. A formal induction process for volunteers is crucial, not only in providing volunteers with the institution’s history and background but also important for the retention of newer volunteers (Connors, 2011). Volunteer training should be more than just skill training – while it is vital for specific roles and techniques, ongoing training can increase volunteer satisfaction and improve volunteer retention (Stebbins, 2004).

Rewarding and recognising volunteers

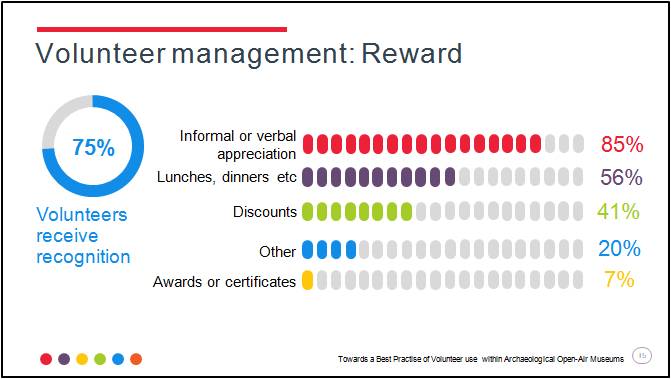

The author found that all the AOAMs offer recognition in one form or another (See Figure 4).

Fig 4. How does your museum reward & recognise volunteers?

The most popular form of recognition is informal / verbal appreciation (39.2%). A large number of institutions provide dinners, lunches or picnics (23%) and discounts on museum items (18.9%). Additional comments indicate that the following forms of recognition are used: allowances, accommodation and food, “Sometimes free beer and food”, “Reduced prices for workshops and copious opportunities to eat cake!”, and “Biscuits and cakes—very important for morale”. Additionally, the Ancient Technology Centre notes: “Our volunteers survive on a heady mix of cake, tea, chat, hard work and dedication and we simply could not do without them”. (Ancienttechnologycentre.co.uk/).

So what motivates volunteers to give freely of their time and skills? Considering the wide geographical and socio-economic situations it is difficult to generalize about motivations. You can’t control the motivations of volunteers and you can’t expect every volunteer to work simply for the ‘good of the organisation’. Having a general understanding of your volunteers’ motivations can significantly increase the retention of experienced volunteers and attract new ones (See Figure 5).

Fig 5. What motivates your museum’s volunteers to give their time?

It has been shown that volunteers who received benefits that matched their motivations were more satisfied with their volunteer experience. Using this model, this research indicates that the most important motivation for AOAM volunteers is the desire to learn new skills through direct, hands-on experience, followed by the opportunity of enhanced social opportunities and forging of new relationships.

Positive social interactions are not just with other volunteers but with staff and, most importantly, with visitors. Motivation is deeply personal and often not completely understood by the individual. The effective volunteer manager shapes reward to reflect the motivations and drives of a variety of volunteers. Understanding a volunteer’s motivations can increase their happiness and their commitment. It is essential not only in retaining experienced individuals but also attracting new volunteers.

Evaluating volunteers

Notably 75% of responding institutions do not provide ongoing evaluation for volunteers. Ongoing evaluation is essential to the continued success of volunteers and the institution. Evaluation provides opportunities for positive reinforcement and the opportunity to tackle issues as they arise (Kuyper, Hirzy, and Huftalen, 1993)although can also be time-consuming and potentially uncomfortable for everyone involved. Not everyone likes to be critiqued or indeed to critique other people. Perhaps such evaluation is best viewed as an opportunity to give positive reinforcement and examine discretely any areas of potential conflicts. Volunteers should be evaluated for the quality of work they perform, and have the opportunity to evaluate their own experiences. Their feedback and suggestions should be taken seriously by staff.

The best evaluation is a two-way street. With only a quarter of our institutions performing regular evaluation more support could be offered to museums interested in using evaluation as a best practice tool.

Summary

The AOAMs in this study represent a nuanced approach to volunteers that may not be relevant to museums as a whole. While the uses of volunteers in AOAMs reflect those of museums in general (e.g. interpretation, information, and exhibits), this particular type of heritage presents volunteers with unusual environments and work opportunities such as the presentation of traditional crafts and reconstruction of traditional building types (Figure 22). The interpretation of traditional crafts is a critical function of the AOAM and is indicative of the Scandinavian, folk and agricultural origins of this type of museum (Zuraini and Zawawi, 2010). The author posits that the volunteer involved in folk-craft presentations may often be a skilled individual rather than a casual volunteer. While the construction of specific, archaeologically-justified building types may require particular skills, volunteers can be involved in the development and construction of structures (David deClercq, personal communication, 2014) and more mobile displays, such as boats (Pavel Biletsky, personal communication, 2014).

For the archaeological open-air museum, the fundamental objectives of education, interpretation and archaeology are all resource-intensive (Zuraini and Zawawi, 2010). These missions, combined with the costs to care for an open-air ‘park’, maintenance of recreated buildings, heavy reliance of public funds and relatively small visitorship create fundamental challenges of sustainability (Paardekooper, 2012). Some of these AOAMs have very low visitorship rates of around 5,000 per year. Because of their origins in the archaeology of a particular region, the interpretive narrative is often very specific, both temporally and spatially, and the interpretive methodologies can be narrow (Paardekooper, 2012). Many of these AOAMs were initialized by charismatic founders and as such face the challenge of transitioning to a more fiscally-balanced and heritage tourist-driven organisation. All of these factors support a necessary reliance on volunteers without whom many European AOAMs might fail.

The author has demonstrated that the use of volunteers in AOAMs is widespread and the small number of volunteers is representative of the relatively small size of many of these institutions. However, a number of museums (such as Butser and Eindhoven) utilise large numbers of volunteers. The author surmises that this is a function of commitment to volunteering, location / community, and history -Butser was founded in 1970 and Eindhoven in 1982. Moreover, Sagnlandet Lejre (founded in 1964) utilizes over 200 volunteer hours per week.

Many archaeological open-air museums face growing economic challenges (Paardekooper, 2012). However, the growing prevalence and proven popularity of these educational and entertaining heritage sites indicate a strong future for many museums. A strong volunteer program can maximize the interpretive potential and strengthen engagement with the community which in turn encourages more volunteerism and increases visitation. Volunteer resources engaging in interpretation and traditional crafts can positively affect tourist engagement and secondary spend. For many AOAMs, volunteers are a must: not only to maximise interpretive impact for the visitors but simply to keep the doors open. With relatively small attendance rates and even smaller budgets, many of our AOAMs could not exist without volunteers. As such, an organised volunteer program is a must for smaller or new sites. We should also remember that a significant number of our institutions are completely run by volunteers. Without their dedication we would not have the rich variety of institutions that we currently enjoy. As a heritage community we must find innovative ways of supporting new institutions through the sharing of knowledge and experience. EXARC is a great foundation but more can be done.

While this study is limited in scope and every institution works in a unique environment there are a few findings that can help to develop volunteer capacity and sustainability including:

- A designated volunteer coordinator is both an effective use of organizational funds and vital for the continued success of the volunteer program and museum.

- Active recruitment that uses methodologies that work for you

- High quality orientation and ongoing training is essential in retaining and improving the morale of volunteers.

- Ongoing two-way evaluation can improve volunteer satisfaction and provide much needed communication between staff and volunteers.

- A wider variety of flexible non-traditional volunteering options.

- Increased sharing of information, data, and best practices through EXARC (organizational standards).

Further studies should focus on the motivations of volunteers in order to correctly match recruitment, training and retention efforts with the diverse needs of potential volunteers.

AOAMs could do more to attract younger volunteers using social media.

Keywords

Country

- United Kingdom

Bibliography

ARCHAOLOGISCHES FREILICHTMUSEUM OERLINGHAUSEN

Afm-oerlinghausen.de/index.php?lang=de, accessed March 31st 2014

AMBROSE, T. & PAINE, C. 2012. Museum Basics. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

ANCIENT TECHNOLOGY CENTRE. Ancienttechnologycentre.co.uk/, accessed March 31st 2014

ANGERMANN, A. & SITTERMANN, B. 2010. Volunteering in the Member States of the European Union - Evaluation and Summary of Current Studies. Working Paper no. 5. Observatory for Sociopolitical Developments in Europe.

http://www.sociopolitical-observatory.eu/uploads/...

THE BOYNE CURRACH. Newgrangecurrach.com, accessed March 31st 2014

BUTSER ANCIENT FARM. Butserancientfarm.co.uk, accessed March 31st 2014

CALAFEL HISTORIC. Calafellhistoric.org, accessed March 31st 2014

CELTIC HARMONY. Celticharmony.org/ accessed March 31st 2014

CHAMBERS, D. 2002. Volunteers in the Cultural Sector in England. Institute for Volunteering Research. http://www.ivr.org.uk/component/ivr/volunteers-in-the-cultural-sector.

CONNORS, T.D. 2011. The Volunteer Management Handbook: Leadership Strategies for Success (Wiley Nonprofit Law, Finance and Management Series). 2 edition. Wiley.

CORSANE, G. 2005. Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introductory Reader. London: Routledge.

THE SCOTTISH CRANNOG CENTRE. Crannog.co.uk, accessed March 31st 2014

CSORDAS, I. 2011. Volunteer Management in Cultural Institutions. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. http://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/topics/Volonteering/Volun….

CURIA VITKOV. Curiavitkov.cz, accessed March 31st 2014

MUSEUMDORF DUPPEL. Dueppel.de, accessed March 31st 2014

EINDHOVEN MUSEUM. Eindhovenmuseum.nl, accessed March 31st 2014

EGMUS. Egmus.eu/nc/en/statistics/complete_data/z/0/, accessed April 4th 2014

FOTEVIKENS MUSEUM. Fotevikensmuseum.se/d/en/home, accessed March 31st 2014

GALLISHE HOEVE. Gallischehoeve.be/, accessed March 31st 2014

GESCHICHTSERLEBNISRAUM LUBEK. Geschichtserlebnisraum.de/, accessed March 31st 2014

GIBBS, K & SANI, M. 2009. Volunteers in Museums and Cultural Heritage. Slovenian Museum Association. http://www.amitie.it/voch/VoCH_Final_Publication_EN.pdf.

GOODLAD, S. & McIvor, S. 2012. Museum Volunteers: Good Practice in the Management of Volunteers. London: Routledge.

WIKINGER MUSEUM HAITHABU. Haithabu.de, accessed March 31st 2014

HISTORY MATTERS. Historymattersonline.com, accessed March 31st 2014

HILL, J. 2008. Recruiting and Retaining Volunteers – a Practical Introduction. AIM. www.museums.org.uk/aim.

HOWLETT, S., MACHIN, J., & MALMERSJO, G. 2005. Volunteering in Museums, Libraries and Archives. Institute for Volunteering Research. http://www.volunteerspirit.org/files/volunteer_survey_2006_9500.pdf.

VEIEN KULTURMINNEPARK. Hringariki.no, accessed March 31st 2014

KOBIALKA, D. 2013. The Mask(s) and Transformers of Historical Re-Enactment: Material Culture and Contemporary Vikings. Current Swedish Archaeology 21: 141–61.

KUYPER, J., HIRZY, E.C., & HUFTALEN, K.R. 1993. Volunteer Program Administration: A Handbook for Museums and Other Cultural Institutions. New York: American Council for the Arts in association with the American Association of Museum Volunteers.

PROVINCIA DI TREVISO. Livelet.provincia.treviso.it, accessed March 31st 2014

LOFOTR VIKINGMUSEUM. Lofotr.no/index.asp, accessed March 31st 2014

LOWENTHAL, D. 1998. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press.

MCCURLY, S., LYNCH, R., & VESUVIO, D.A. 1989. Essential Volunteer Management. Downers Grove, IL: VMSystems and Heritage Arts Pub.

MATRICA MUZEUM. Matricamuzeum.hu, accessed March 31st 2014

OLESHYE. Oleshye.com.ua/, accessed March 31st 2014

PARCO ARCHAEOLOGICAL DEL FORCELLO. Parcoarcheologicoforcello.it, accessed March 31st 2014

PAARDEKOOPER, R. 2012. The Value of an Archaeological Open-Air Museum Is in Its Use: Understanding Archaeological Open-Air Museums and Their Visitors.

SAGNLANDET LEJRE. Sagnlandet.dk/English.425.0.html, accessed March 31st 2014

SANDELL, R. Janes, R.R. 2007. Museum Management and Marketing (Leicester Readers in Museum Studies). Routledge.

STIKLESTAD NASJONALE KULTERSENTER. Stiklestad.no, accessed March 31st 2014

STEBBINS, R. A. & GRAHAM, M. 2004. Volunteering as Leisure/leisure as Volunteering an International Assessment. Wallingford, UK; Cambridge, MA: CABI Pub.

WANG, N. 1999. “Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience.” Annals of Tourism Research 26 (2): pp. 349–70.

WRIGHT, P. 1985. On Living in an Old Country: The National Past in Contemporary Britain. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

YOUNG, L. 2006. Villages That Never Were: The Museum Village as a Heritage Genre. International Journal of Heritage Studies 12:4: pp.321–38.

ZURAINI, M.A. & ZAWAWI, R. 2010. Contributions of Open Air Museums in Preserving

Heritage Buildings: Study of Open-Air Museums in South East England. Journal of Design and Built Environment 1 (December).