The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Living History as an Instrument for Historical and Cultural Exchange in German Archaeological Open-Air Museums: an Online Survey Defines Present Status

The topic of Living History is a controversial one, with diverse opinions on its subject matter. To begin with: What does the term Living History mean? And in what context do we discuss it? Living History has long been utilized as a method of experiencing history and cultural exchange in open-air museums, especially outside of Germany.

In Germany, for several years now it has become increasingly significant as a means of reflecting the cultural exchange of archaeological open-air museums, as well as in scientific discussions and interdisciplinary meetings1 . Now, at the forefront of the debate are the issues of definition, the manner of presentation, and the execution of museum education.

In 2015, Tatjana Meder, Jana Seipelt and Sabrina Slanitz established a study group at the European University in Frankfurt/Oder, as part of the degree programme "Protection of European Cultural Heritage" under the direction of Prof. Dr. Paul Zalewski, as a project to study this issue. Initially, after an intensive examination of the literature and discussions with Dr. Roeland Paardekooper, the focus was to determine the current status of Living History as a museum education tool in teaching history and intangible cultural heritage in German archaeological open-air museums. This was accomplished using a quantitative customized data collection instrument and a subsequent qualitative survey in the form of interviews with experts in the field. Both surveys were conducted by means of an online questionnaire. The surveys inquired as to how history is taught and what the integration of Living History actually looks like in open-air museums.

Since the entire population of archaeological open-air museums in Germany, (85 institutions) was surveyed, the dataset constitutes a full census; however, the response rate was 42,4%.2 The questionnaire was analysed with the statistical program Grafstat 3

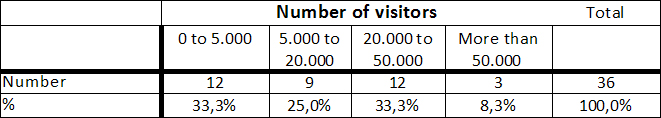

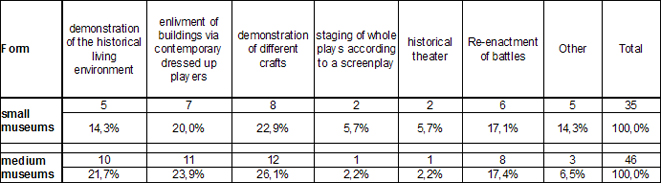

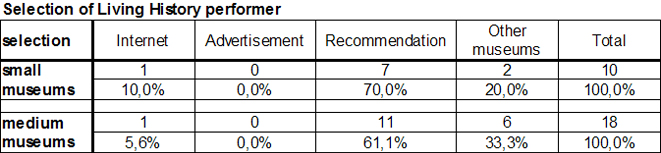

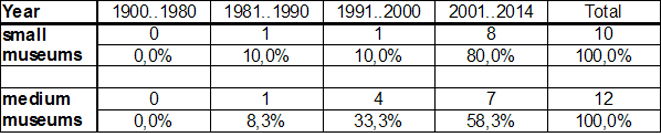

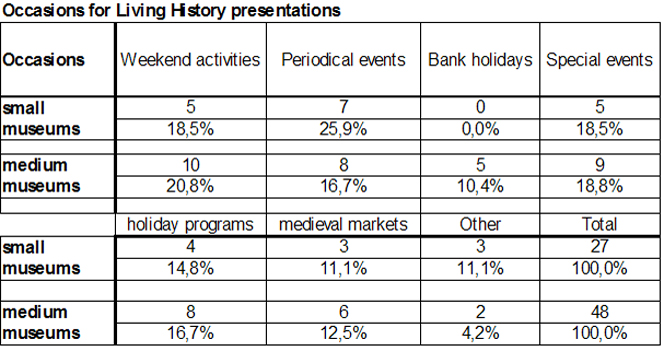

Museum directors and heads of educational departments of the archaeological open-air museums were asked 15 questions on various topics. Some questions considered more general subject matters, for example the annual number of visits, educational programmes at the museums, and defining employees in terms of full-time, part-time and volunteer staff. Furthermore, there were asked specific questions about the design, the form and the specific audience of Living History, as well as the selection of the performers. For the purpose of analysis, participating museums were divided based on average annual numbers of visitors; small museums (5,000 visits), small to medium museums (5,000-20,000 visits), medium museums (20,000 – 50,000 visits) as well as major museums (more than 50,000 visits). The study investigated in detail two groups of museums (discerned by annual visitor numbers) using comparative analysis to elaborate how small museums are set up in comparison to medium museums.

In summary, it can be stated that the size of a museum influences the following factors: how many events are offered, the number of employees available, the number of forms of Living History per museum, and to a lesser extent on how the Living History performers are selected, as well as whether the performers are trained, and finally on the number of occasions (quantity) in which Living History is offered per museum.

Survey results indicated that the size of the museum has little to no effect on the time period Living history represents, the words used to describe Living History; the occasions when Living History is offered; the target group; the form in which Living History is available and finally who performs Living History.

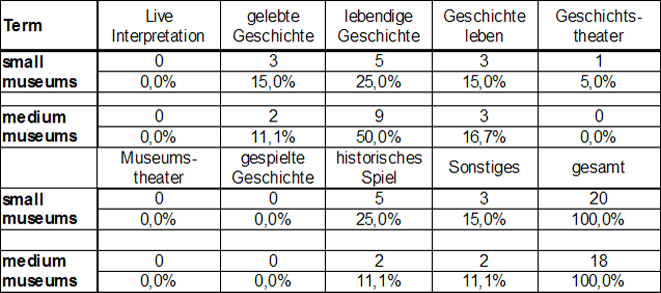

Since the term Living History continues to trigger debate among experts, it was asked if other terms were used in the place of Living History at the museums. It is striking that for both large and small museums the use of other terms was common. While the distribution among small museums is more uniform, there is a concentration of specific terminology in larger museums. Half of the large museums used "living history". Some large museums also used "live history" (Geschichte Leben), "living history" (Lebendige Geschichte) and "historical game" (Historisches Spiel). One quarter of small museums used "living history" and another 25% used "historical game". Phrases like "Live Interpretation", "Museum Theater" and "Played History" (Gespielte Geschichte) are not used.

Individual museums used the "Other" field, which provided additional terms to those that had been offered. Small museums used terms such as "experience leadership" and "experience history". Two of the large museums gave the terms "re-enactment" and "applied archaeology". This clearly shows the difficulty associated with the delineation and definition of Living History and highlights the plethora of terms in use.

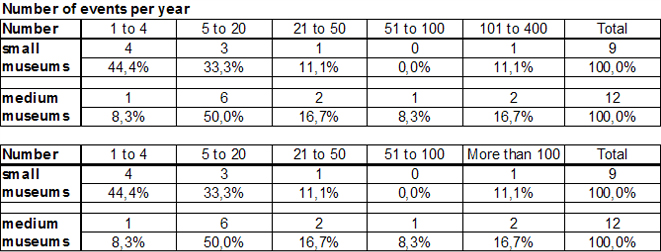

In terms of the question regarding the number of annual Living History events, results showed that almost half of the small museums held 1 to 4 events a year. Slightly less than half held between 5 and 20 events, and one museum held between 100 and 140 events. Exactly half of the large museums indicated that between 5 and 20 events had taken place annually. Only a few large museums held 1 to 4 events.

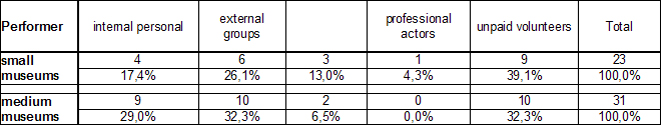

The most significant difference in responses to the question regarding who performs Living History was seen in terms of the number of museum staff. Significantly more large than small museums reported that Living History is carried out by the museum with its own staff. For both small and large museums, volunteers most commonly performLiving History. Large museums often use external groups. Both types of museums hire non-professionals for Living History.

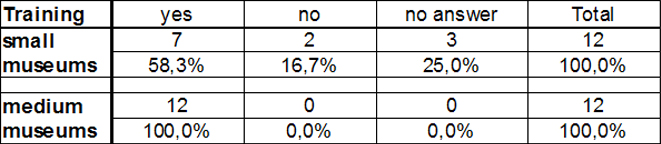

All large museums, where internal staff perform Living History, also provided training. In contrast, only 60% of small museums answered "yes" to this question. A quarter of small museums responded no to this question.

A detailed consideration of the results highlights the following:

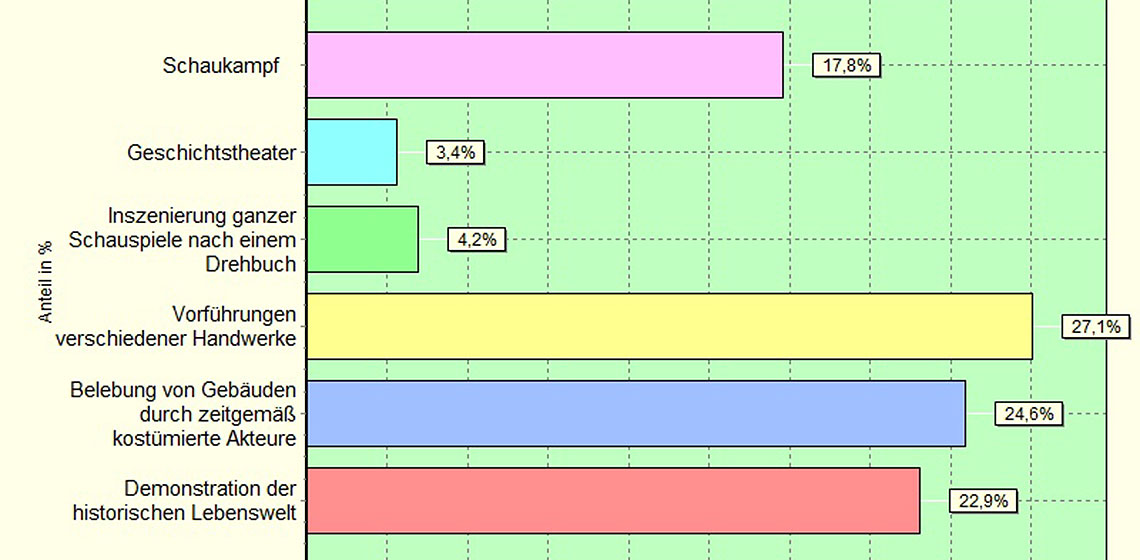

It is remarkable/striking that all of the responding museums offered Living History as an interpretation tool. Thereby it does not matter whether the museum is small or large. Various craft techniques are demonstrated. In addition, structures are enlivened with costumed reenactors and demonstrations of historical lifeways. Some museums stated that they offer scenic tours and courses on traditional crafts. The target group analysis revealed that archaeological open-air museums often offer specific Living History programmes for schools, especially primary school and secondary school. Furthermore, families are the most important target group who receive tailored programmes using Living History.

Following the quantitative survey, the study group asked five experts from museology as well as from academic and scientific fields which employ Living History methods, to answer five specific questions on the subject. This will further detail the Living History methods used, their opportunities, as well as difficulties associated with the practice.

The first question aimed to learn from respondents what they understand about the term Living History. With the exception of some basic similarities, the answers provided are all quite different. For example, respondents indicated that the "representation of individual sets" and, the "display of crafts", should be included under this term. One expert suggested that it should always have “something to do in any case with the revival of a place, preferably at an historical site or museum"4 . Another response highlights the issue of authenticity, which should be respected without question in Living History - "in a vivid and appealing manner provide a narrative, human to human, and thereby incorporate the most authentic clothing, devices used." Here, parallel with another expert is recognition that authenticity is regarded as essential, “Authenticity is regarded as essential by another expert also” "historically authentic activities in an appropriate context". Furthermore, Living History is needed to "attempt the active appropriation of the past, and thus the practical / emotional / physical experience of the past brought to the present". This respondent also felt that, Living History clearly borders terms like ’re-enactment’ and ‘experimental archaeology’, and foresees "Living History as an umbrella term that includes these same phenomena". Another person however mentioned role-playing in the fields of experimental and primitive technologies in the presentation of crafts. All of the responses provided a vibrant and active representation of the experience of the past achieved through Living History. Unanimously, Living History continues to be known as an authentic "representation of, given the present state of science, authenticated or plausible events and activities of past eras".

The respondents saw the two largest difficulties facing Living History as

- the lack of professionalism of the performers

- the lack of historical background knowledge of the performers which may lead to a "false view of history" which is received by the audience through portrayal.

Moving beyond anachronisms and authenticity, there is also the issue of language. "Authenticity will never be achieved, although everyday objects [...] can be reconstructed based on appropriate resources available, but the mental, social and religious sphere is now largely closed". Despite these difficulties, there are nevertheless some obvious benefits to the practice of Living History. In addition to the revitalization of the museum other benefits include knowledge transfer and direct contact between visitor and object - the "tactile experience" and "as a positive side benefit, increasing the number of visitors" for mediating essential knowledge through Living History. Here, discussion with stakeholders should take place to avoid disputes spread by "false" actors, for example, by "esoteric / neo-pagan groups as well as the exploitation by right-wing extremist circles".

Participants were also questioned as to whether there are events with notably positive responses and experiences in terms of Living History. Repeatedly, something that was discussed here was “participatory events", such as "archery", and "touch and try" events. All respondents said that they were getting very positive responses to their contributions. Respondents also had an overwhelmingly positive experience when engaging stakeholders in open dialogue.

Finally, we asked whether the experts see a need for action in mediating the topic of Living History, and if so what form this mediation would take? All respondents agreed that action is needed with responses consistently referring to the quality of the shows, in relation to "science and the available sources of appropriate display", and also in relation to dealing with the public. Some solutions to these issues have been suggested such as, training courses for actors with regional museum associations, and EXARC inclusion as a potential host. Furthermore, a list of requirements is to be imposed on Living History demonstrations at museums, which must be adhered to as means of quality control. One interviewee in this respect indicated that attempts had been made over the last five years to improve the exchange of information in the form of the ‘International Reenactmentmesse’. "Herea history performer can be supplied with suitable gear and enter in discussions with professionals [...]." "Together the concepts are being developed in order that the subject is scientifically taken seriously", since it is precisely within the museum context that Living History as a method of delivery will become increasingly important.

The study has shown conclusively that Living History is a topical issue and is a method that is widely used in German archaeological open-air museums. At the same time there is also the need to act with respect to quality control to ensure that intangible cultural heritage is experienced through Living History in a professional manner, thus protecting the practice. The survey serves to investigate the point at which archaeological open-air museums in Germany are with regard to Living History.

The aims and objectives of this project have been successfully met in that the results obtained from this survey have highlighted the current status5 of Living History in German archaeological open-air museums. Furthermore, they indicate that individual museums have the capacity to act as an evaluation tool for their own organization. In this manner they can determine their own position and identify potential areas in need of reform if/where they exist. The interviews with experts in the field identified problems which are still present and ongoing, and have established ways in which action might be taken to address those perceived shortfalls.

- 1The technical literature shows the current debate of Living History. Actors and museum directors discussed over the years the meaning of this method for archaeological open air museums for example in: Hochbruck (2013), Klöffler (2008), Apel (2008) or Samida (2010, 2012).

- 2Initially it was assumed a total of 95 institutions could be utilised during data collection. (However, a number of the museums have not been included in the results as they did not meet the technical requirements that constitute an open-air museum). (Furthermore, the Archaeological Freilichtmuseum Oerlinghausen is involved indirectly as a partner and therefore could not be included, bringing the total number of respondents incorporated in the overall survey results to 85.

- 3The process of the evaluation based on a selection of literature, for example: Bortz and Döring (2006), Diekmann (1996), Raab-Steiner and Benesch (2012), Schumann (2012).

- 4From the questionnaire answers

- 5As of 2015

Country

- Germany

Bibliography

APEL, G. (2008). „Vivat tempus“ oder Geschichte und Alltagskultur als Abenteuer im Freilichtmuseum? Chancen und Risiken personaler Vermittlung im LWL-Freilichtmuseum Detmold. In: Carstensen, Jan; Meiners, Uwe; Mohrmann, Ruth E. (eds):Living History im Museum. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen einer populären Vermittlungsform. Beiträge zur Volkskultur in Nordwestdeutschland. Band 111, Münster: Waxmann. pp. 101-117.

BORTZ, J.; DÖRING, N. (2006). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler, Heidelberg: Springer.

DIEKMANN, A. (1996). Empirische Sozialforschung: Grundlagen, Methoden, Anwendungen, Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch.

HOCHBRUCK, W. (2013). Geschichtstheater: Formen der Living History. Eine Typologie, Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

KLÖFFLER, M. (2008). Living History in Museen. Aus der Sicht von Akteuren, In: Carstensen, Jan; Meiners, Uwe; Mohrmann, Ruth E. (eds): Living History im Museum - Möglichkeiten und Grenzen einer populären Vermittlungsform. Beiträge zur Volkskultur in Nordwestdeutschland. Band 111, Münster: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 135-150.

RAAB-STEINER, E.; BENESCH, M.(2012). Der Fragebogen: Von der Forschungsidee zur SPSS/PASW Auswertung. Stuttgart: UTB.

SAMIDA, S. et al. (2010). Was ist und warum brauchen wir eine Archäologiedidaktik? Reflexionen über eine vernachlässigte Aufgabe archäologischer Forschung. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtsdidaktik: Band 09E, Ausgabe 1, pp. 215-226.

SAMIDA, S. (2012). Re-Enactors in archäologischen Freilichtmuseen: Motive und didaktische Konzepte. DGUF-Tagung 2012 in Dresden, in: Archäologische Informationen 35, pp. 209-218.

SCHUMANN, S. (2012). Repräsentative Umfragen. Praxisorientierte Einführung in empirische Methoden und statistische Analyseverfahren. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 6th print.