The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Build It and They Will Come: Managing Archaeological Open-Air Museums in Britain for Stability

Museums are among the most visited attractions in the UK (ALVA 2015), and with interactive displays and active engagement becoming more commonplace, this success can be capitalised on by archaeological open-air museums. Some European archaeological open-air museums entertain many visitors per year, although most are smaller institutions (Paardekooper 2012). Whilst footfall and support of visitors is important in determining the stability of such sites, it is their management that determines attractiveness to visitors. To determine these aspects, a questionnaire was filled in by seven EXARC affiliated archaeological open-air museums in the UK examining financial, social and staff stability, as well as any additional affiliations.

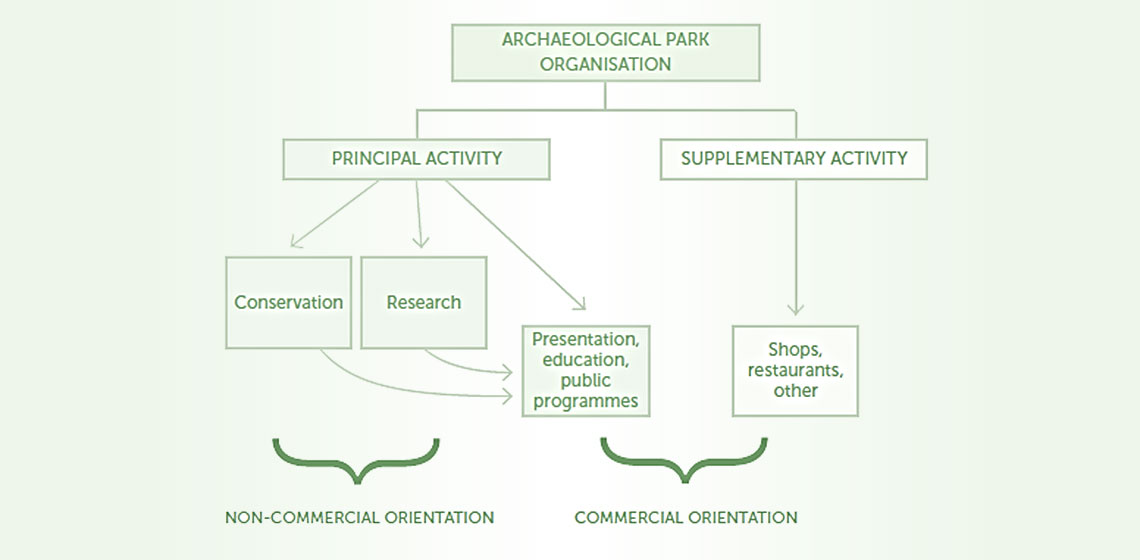

Image Above: Diagram of commercial and non-commercial activities in an archaeological open-air museums ©Breznik 2014:176

Financial stability

This article defines a financially stable museum as being one with a stable or increasing profit. Due to the expectation that many sites may be reluctant to reveal financial details, this question was divided into broad categories to provide a general picture.

The results shown in Table 1 indicate that Butser, Celtic Harmony, The Ancient Technology Centre (ATC), West Stow, and the Scottish Crannog Centre can be considered financially sustainable. The three sites which report increasing profits mention two main factors that have contributed to this rise: school curriculum changes and increased interest in the subject area. The recent change in curriculum now states that Key Stage 2 pupils must learn about “changes in Britain from the Stone Age to the Iron Age” (Department for Education 2013:3), which Butser and Celtic Harmony are well placed to provide, and both state that the rise in profits is directly due to this change. The Ancient Technology Centre states that profit rise is due to more interest in the construction of buildings and the increase in the number of commercial projects undertaken. Such an example is their construction of the Neolithic houses at Stonehenge for English Heritage. This may be connected to the curriculum change which includes “Britain’s settlement by Anglo-Saxons” (Department of Education 2013:4) and is estimated to provide a valuable source of future income for the site, as many primary school teachers do not have the grounding in prehistory or early history to feel confident in teaching such topics. Education sessions provided by museums that fulfil these curriculum areas, therefore, are seen to be good value for money.

| Increasing | Stable | Decreasing | Declined to say |

| Butser | West Stow | Flag Fen | St Fagans |

| Celtic Harmony | The Scottish Crannog Centre | ||

| ATC |

Table 1: Table showing the reported profit trend

The prehistoric Flag Fen has not seen a similar jump in profits but, instead, reported a decrease due to low visitor numbers. This is due to the differing target audience of academics, special interest groups and families on event days, instead of schools. It also recently moved management from the Fenland Archaeological Trust to Vivacity, a local government company which specialises in leisure, culture and tourism (Vivacity 2015). Indeed, the Vivacity website advertising Flag Fen does not appear to offer any educational programmes for schools, thus failing to take advantage of the curriculum change. In addition, whilst the archaeological site was crowdfunded in 2012 with DigVentures (2015), which raised over £30,000 and increased visitors by 30%, the site now runs on a government subsidy.

Whilst St. Fagans declined to answer, it was suggested that recent government cuts had hit the site hard. This is despite the recent £450,000 HLF grant in 2010 (Museum Wales 2011), and receiving most capital investment in 2012/13 by Amgueddfa Cymru (Museum Wales 2013:6) to update visitor facilities. The independent Butser, Celtic Harmony, and Crannog Centre have grown out of public donations and private investment and as such, are not so affected by government money being withdrawn, making them more sustainable today. However, the economic downturn may affect them indirectly. The Crannog Centre reported that, whilst visitor and profit levels were stable, this was at a lower level than in previous years due to rising fuel prices – an important factor due to the remoteness of the site - fluctuating currencies, and the credit crunch.

West Stow and The Ancient Technology Centre, on the other hand, both operate under government management and yet maintain a stable profitability. West Stow reported that this was because the Anglo-Saxon content is on the current key stage 2 curriculum (Department of Education 2013:4) resulting in a 50% increase in school visits. In addition, like St. Fagans, a reliance on spending in the shop and café was mentioned. Large family events also help to maintain a stable profit line. Marketing for such events, as well as day-to-day running, is essential, with Butser attributing some of its rise in profits to a raised profile through films, TV, and advertising. To maintain stable or increasing finances, the profits made through these ventures needs to be high enough to support the non-profit generating parts of the museum, such as ongoing construction (e.g. roundhouse re-roofing) and research (Fig 1. Diagram of commercial and non-commercial activities in an archaeological open-air museum ©Breznik 2014:176).

Overall, the current cuts to funding and unexpected expenses, such as re-roofing the Flag Fen roundhouse, are the main reasons for not achieving financial stability. The more successful sites are achieving good profit levels through capitalising on school curriculum links and thus proving their educational worth, although the value of a profitable shop and the organisation of larger one-off events cannot be ignored, especially if there are fewer schools in the area, or less money to pay for school visits.

Social stability

Stable visitor figures do not have to be high to be sustainable – too many visitors in a small museum space is just as detrimental as no visitors (Davies, Wilkinson 2008:17) as the experience will be diminished due to queues and / or crowds, thus resulting in fewer repeat visits and a lesser educational impact. As such, these figures will be compared to the space used by the museum, after which the degree to which the museum monitors visitor happiness will be explored.

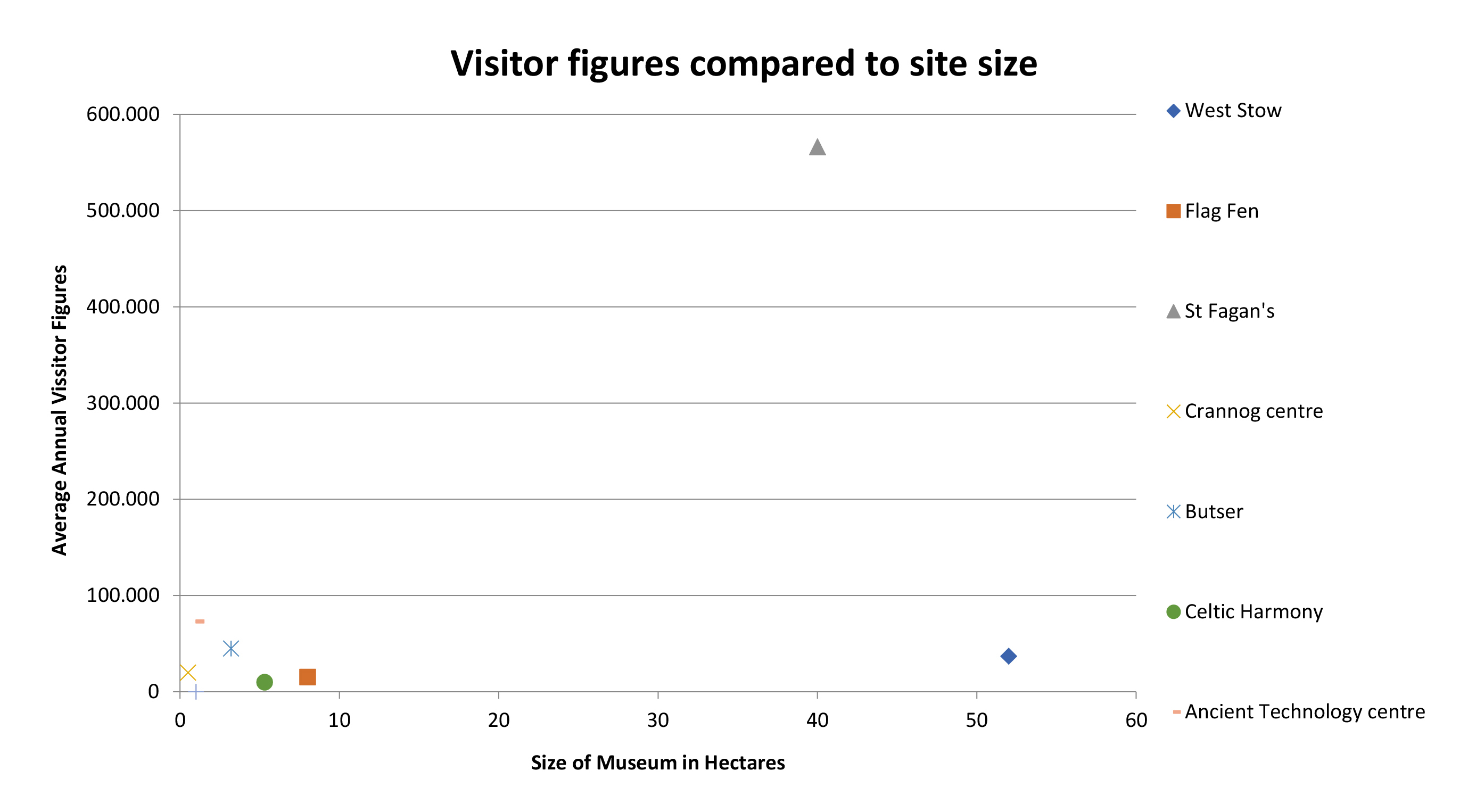

Graph 1. Visitor figures compared to site size

A clear relationship does not appear to exist between the numbers of visitors and size of the museum as shown in Graph 1. The smaller museums with a higher visitor figure, such as the Ancient Technology Centre, appear to be accommodating the most visitors per hectare, whilst West Stow is accommodating the least. However, it must be borne in mind that West Stow is the archaeological site of an Anglo-Saxon village and requires the larger space to preserve it. Flag Fen also has this consideration.

St. Fagans comes from a traditional museum background, whilst all the others started with hands-on activities, which require higher levels of supervision and direction, and thus fewer visitors can be catered to concurrently, thus resulting in the difference in visitor figures. This data indicates that space is not essential for financial or social growth – more important is the way in which the land is used to return a good rate of investment (Davies, Wilkinson 2008:8).

| System of visitor feedback | Performance measures for the museum | |

| West Stow | x | |

| Flag Fen | x | |

| St Fagans | x | x |

| Crannog centre | x | x |

| Butser | x | |

| Celtic Harmony | x | |

| ATC | x | x |

Table 2: Table showing use of feedback mechanisms

Most of the sites use a visitor feedback system as shown in Table 2. Indeed, Paardekooper’s results (2012:232) indicate that this is the most common method of gathering feedback across Europe. Most of the sites use social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, and online rating sites, such as Trip Advisor, as a way of analysing what visitors find good or bad. However, these methods rely on the visitor providing feedback, which tends to occur when the visitor is either annoyed or extremely pleased with an aspect. As such this does not consider the opinions of the silent majority. An alternative technique is that of the ‘mystery visitor’, a system tested in Germany with good results. A group of people representative of the museum’s audience anonymously visit the museum, grades aspects of its service, and files a comprehensive report (Kirchberg 2000). Such a system clarifies how successful the museum is from a visitor’s viewpoint, but is only possible in museums with larger resources. An alternative would be to invite groups e.g. mother and toddler, disability or faith groups, or inviting in a number of people from different local companies for a free visit on condition of filling in a comprehensive survey as they go round.

Most of the sites using other performance indicators use income-related targets. However, St. Fagans stands out as using a whole range of measures for performance. This is due to its establishment as a national museum. These performance measures include impact assessments, visitor profile data, and visitor figure data, in addition to recording performance in the number of museum partnerships being maintained and academic publications. Staff performance was recorded through the percentage of sick days taken and number of volunteers involved. The amount of focus on visitor feedback, translating into improved visitor marketing, services, and engagement seems to have worked, with St. Fagans experiencing a 74% increase in visitors since 2000, and a 4% increase since 2013 (Museum Wales 2015). However, it is not feasible for smaller sites to collect such large amounts of data. The most important measures that smaller museums ought to consider should include the education provided by the museum, how visitors needs and expectations are met, and how economically efficient the site is (Breznik 2014:91; Hudson 2009:20; Jackson 1991:61; Negri 2009:8). Whilst performance measures are useful in keeping a museum focused on targets, which help to ensure the deliverance of the site’s mission statement, it is important that the return value is greater than the resources spent completing them.

Staff stability

A good ‘value for money’ model runs a museum on a core number of full-time staff, supported by part-time or seasonal staff. These paid staff should be outnumbered by a well-managed volunteer body to relieve high workloads whilst creating a sense of local community ownership (Frevert 1997:150).

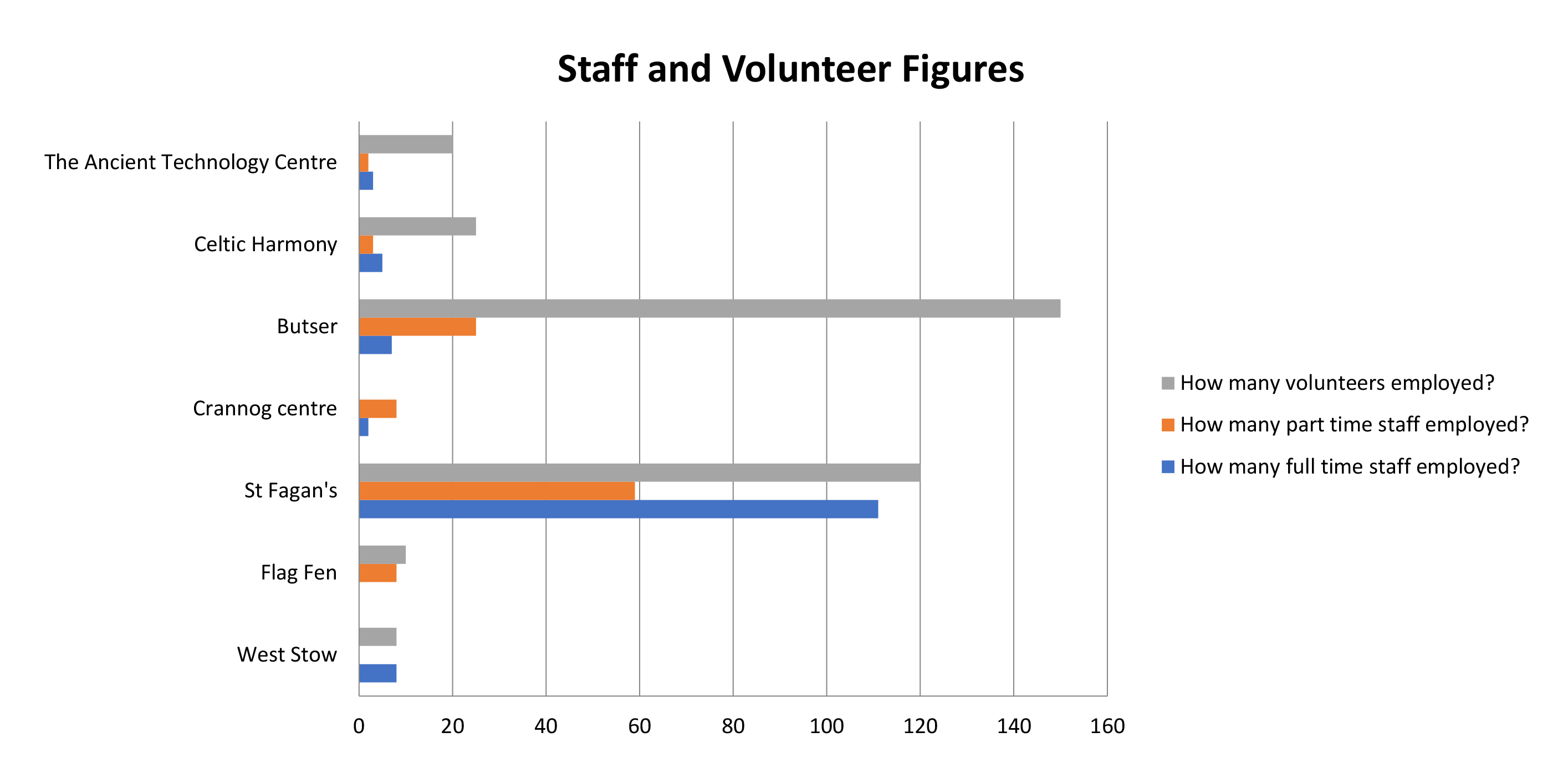

Graph 2. Staff and volunteer figures

The results in Graph 2 indicate that Celtic Harmony, Butser, and The Ancient Technology Centre follow the model, with a few core staff and many volunteers - these are also the museums reporting increases in profits and visitor figures. St. Fagans and West Stow follow a similar model. This, therefore, suggests that running the site on a large volunteer workforce is not off-putting to visitors and helps to drive costs down. Indeed, 90% of archaeological open-air museums across Europe use volunteers, and 17% are run by volunteers alone (Spencer 2015).

However, this is not the only staff model that works. The Scottish Crannog Centre does not use any volunteers due to the lack of accommodation (Andrian 2015), yet reports a stable financial position. The benefit of this system is that all staff will have a high level of knowledge about the period covered through training or academic learning. However, the Scottish Crannog centre also reports that staff retention is hard, as most need to find alternative jobs over the winter to supplement their income when the centre is not open (Andrian 2015), thus eroding this benefit. Flag Fen, on the other hand, employs no full-time staff. However, the low volunteer figures are surprising, considering the amount of community involvement experienced during the archaeological dig through the crowdsourcing process which led to increased visitor figures and global online following (DigVentures 2015).

Overall, the model that ties in with the most financially and socially stable museums appears to be one where the volunteer figures outweigh the paid staff. However, this is a broad comment, as the number and effectiveness of volunteers depends on the volunteer environment, how well volunteers are retained, how many hours are worked by the volunteers, and the accessibility of the site. Thus, this staff model may not result in success, but could generally be an indicator of good management of museum affairs. However, it follows that a well-managed, large volunteer workforce can be helpful to any site.

External affiliations

| Does the museum maintain any external affiliations? | ||||||

| University | ICOM | Tourism / business network | The Museums Association | Government | Other | |

| West Stow | x | x | x | x | ||

| Flag Fen | x | |||||

| St Fagans | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Crannog centre | x | x | x | x | ||

| Butser | x | x | x | |||

| Celtic Harmony | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ATC | x | x | x | |||

Table 3: Table showing external affiliations of sites.

As shown in Table 3, Butser reported that maintaining affiliations with other bodies, in this case the South Downs National Park, helped to raise the profile of the site, whilst many of the other sites suggested affiliations gave the site credibility. Other benefits mentioned by the sites include access to and help with funding applications, and the opportunity to undertake projects in partnership, which results in a sharing of the resources and finances required.

All of the museums reported that through such associations, standards could be maintained, contacts made and support for projects found. Whilst the benefits of some affiliations are clear, for example, the Scottish Crannog Centre is affiliated with tourist bodies, and has a target audience including tourists, some seem to be lacking. For example, Flag Fen reported that their target audience includes universities and academics, yet maintained no affiliation with a university. Although in 2015 the Crannog Centre did also reiterate that affiliations were essential to maintain visitor and financial stability (Andrian 2015). The Ancient Technology Centre reported that affiliation with a university gave an opportunity to stay in close contact with current experimental archaeology teaching and practice. Thus, the university connection has helped it to remain current in the academic field of archaeology. Partnerships with an academic institution could benefit a site by bringing in extra research and credibility to their projects and bring in on-site experimentation funded by the university department, as well as giving the site academic weight. It should be noted that having been picked for this study through membership to EXARC, all sites are affiliated to it. This affiliation to EXARC provides an alternative source of experimental knowledge and practice through partnerships with other archaeological open-air museums across Europe.

Discussion

Each site has adopted different approaches to management, and indeed, the management practices and styles must be appropriate for the museum if it is to lead them to success. Considering the recent economic downturn; it is both reassuring and surprising to ascertain that archaeological open-air museums are more stable than anticipated, with some even experiencing increasing visitor figures and profits. Whilst unable to rival sites such as Beamish, or similar prehistoric examples in Europe, these archaeological open-air museums are supported by visitors and governed by good managerial sense. The combination of business plans, external affiliations, and taking advantage of curriculum changes appears to work well with sensible financial planning. However, in a changing marketplace, with digital media becoming more prevalent, and changeable economic and political situations, the site must always keep a keen eye out for future opportunities to exploit and evaluate. Institutions such as EXARC are essential in bringing like-minded sites together to learn from each other and support each other’s goals.

Overall, the sites which are experiencing increasing profits and visitor figures – Butser, Celtic Harmony and the Ancient Technology Centre - tie in with the current school curriculum and offer appropriate educational sessions to schools to take advantage of this, small areas are used, and have low visitor figures when compared to bigger museums, such as St. Fagans, and use visitor feedback forms. A greater number of volunteers compared to paid staff are employed, and business plans are used to plan future development with the support of external affiliations. Conversely, the main site which reported decreasing profit levels and low visitor figures – Flag Fen – does not obviously offer any curriculum-based educational programmes, although also maintains a low size, albeit with the added expense of maintaining an archaeological site. It uses visitor feedback forms and employs more volunteers than paid staff, although all staff are part-time. Business plans are used, and some, although not many, external affiliations are maintained. Therefore, the main disparity appears to be the offering of educational programmes. The importance of providing educational facilities and opportunities which were tied into the current curriculum was mentioned many times in the questionnaires. As such this needs to be considered by all archaeological open-air museums who do not offer such programmes.

The results discussed previously, whilst not providing a comprehensive overview of sustainable management for a sustainable business, do appear to point to some general trends that contribute to stability. These form the basis of the three main recommendations for sustainable practice.

- The museum must prove its worth to society and justify to visitors why the expense of a visit is valuable. Proving educational worth is one of the key ways that these examples have increased their profits and thus it is important to review the current educational situation, such as curriculum changes, to remain relevant.

- It is advisable to recruit and retain a large volunteer network. This reduces the workload for paid staff, and reduced training costs when the volunteer network is retained for long periods of time. Volunteers originating from the local community provide a sense of local ownership if well managed, thus creating a more secure support base for the museum in the community.

- Cultivating external affiliations benefits all museums who partake in them by providing support and challenging the museum on how to improve. As such, it is recommended to maintain or create new affiliations.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are given to all the sites which participated in this study, specifically to the staff members who took time out of their busy schedules to fill in the questionnaire and respond to further questions. Further thanks are offered to Dr. Ben Roberts for supervising and guiding this work, and Dr. Roeland Paardekooper for offering advice on studying archaeological open-air museums.

Keywords

Country

- United Kingdom

Summary

Archaeological open-air museums are found across the UK and offer an alternative experience to explore the past to that offered by traditional museums. As such, they are an important means to help engage people with history and prehistory through more interactive activities. However, many are small sites, entertaining few visitors per year. In 2012, Paardekooper published his thesis exploring archaeological open-air museums in Europe; this study seeks to complete a similar, smaller study focusing on equivalent sites in Britain to evaluate how stable such sites are and to produce recommendations for improved management.

After selecting seven sites across Britain, this study compares different aspects of site management to determine which methods best lead to stable archaeological open-air museums. It is argued that whilst the individual characteristics of each museum requires individual management plans, aspects such as tying in the current curriculum, using volunteers to work on site, and using external affiliations to gain credibility and support are important in managing a stable, and therefore long-lived, site.

Bibliography

ALVA (2015) ‘Latest Visitor Figures’ http://alva.org.uk/details.cfm?p=423 (accessed 18/8/15)

ANDRIAN, B (2015) ‘The Scottish Crannog Centre: sustainability in a self-funded archaeological open-air museum- OpenArch Conference, Cardiff 2015’ http://www.slideshare.net/EXARC/the-scottish-crannog-centre-sustainability-in-a-selffunded-archaeological-openair-museum-openarch-conference-cardiff-2015?related=1 (accessed 01/09/15)

BREZNIK, A (2014) ‘Management of an archaeological park’ unpublished PhD dissertation

DAVIES, M., WILKINSON, H. (2008) ‘Sustainability and Museums’ http://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=16398 (accessed 29/08/15)

Department for Education (2013) ‘History programmes of study: key stages 1 and 2’ https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/... (accessed 24/08/15)

DIGVENTURES (2015) ‘Flag Fen 2012’ http://digventures.com/flag-fen-2012 (accessed 24/08/15)

FREVERT, R (1997) ‘Archives volunteers: worth the effort?’ Archival Issues. 22, pp.147-162

HUDSON, K (2009) ‘The concept of Public Quality’ in Negri, M, Niccolucci, F, Sani, M (Ed.) Quality in the museum. Budimpešta: Archaeolingua, pp. 18–21

JACKSON, M (1991) ‘Performance indicators: promises and pitfalls’ In Pearce, S (Ed.) Museum economics and the community, London: Athlone Press, pp. 41-64

KIRCHBERG, V (2000) ‘Mystery visitors in museums: an underused and underestimated tool for testing visitor services’ International Journal of Arts Management. 3, pp.32-38

Museum Wales (2011) ‘Building a home for Welsh history at St Fagans: national history museum’ http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/news/?article_id=660 (accessed 02/09/15)

Museum Wales (2013) ‘Financial Report 2012/13’ Cardiff: National Museum Wales Amgueddfa Cymru

Museum Wales (2015) ‘Culmative Visitor Figures 2014-2015’ http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/... (accessed 24/08/15)

NEGRI, M (2009) ‘From the concept of public quality to the adoption of total quality management models in museums’ in Negri, M, Niccolucci, F, Sani, M (Ed.) Quality in the museum. Budimpešta: Archaeolingua, pp. 7-17

PAARDEKOOPER, R (2012) ‘The value of an Archaeological Open-Air Museum is in its use’ Sidestone press

SPENCER, A (2015) ‘Towards a Best Practise of Volunteer use within archaeological open-air museums: an overview with recommendations for future sustainability and growth - OpenArch Conference, Cardiff 2015’ http://www.slideshare.net/EXARC/towards-a-best-practise-of-volunteer-use-within-archaeological-openair-museums-an-overview-with-recommendations-for-future-sustainability-and-growth-openarch-conference-cardiff-2015 (accessed 01/09/15)

VIVACITY (2015) ‘Flag Fen’ http://www.vivacity-peterborough.com/museums-and-heritage/flag-fen (accessed 14/5/15)