The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Public Access to (Pre-)History Through Archaeology

Public history, like experimental archaeology, is relatively new as an accepted academic program; the two fields are intrinsically linked and should, ideally, use interdisciplinary collaboration to better educate and involve the public in their work. This paper presents case studies in education and interpretation by the author, as well as exemplary programs from various sites in the United States and Europe. In its conclusion, the author suggests best practices for interpretation and public engagement with experimental archaeology through contributory and collaborative work. This paper, an extension of a presentation at the Reconstructive and Experimental Archaeology conference in Williamsburg, Virginia USA in 2017, explores the ways public historians and archaeologists work in museums and historic spaces through artifacts, interpretation, education, and other interdisciplinary undertakings.

The term “public history” is one that practitioners and leaders in the field have struggled to define. In the United States, the National Council on Public History (NCPH) serves as the leading organization for public history and professionals. A section on the NCPH website titled “What Is Public History?” attempts to answer this complicated question. The answer is somewhat complicated, and many self-identified public historians explain the field as “I know it when I see it.” The American Historical Association has also struggled with the definition offered in an article by Robert Weible (2008) titled “Defining Public History: Is it possible? Is it Necessary?”). The NCPH elaborates on their amorphous definition on the council website to explain that “public history describes the many and diverse ways in which history is put to work in the world. In this sense, it is history that is applied to real-world issues” (NCPH online). Public history is an inherently interdisciplinary field, and those who work in it are generally welcoming of professionals in other related fields, such as archaeology, art history, or anthropology.

For the author, a practitioner of public history for ten years, mainly as a museum professional, public history work involves a public audience or community. It is created in the public eye, or with public audiences, and often solves an issue or a problem requiring mediation between academic or professional historians and the public audience or community. When the author first attended the Reconstructive and Experimental Archaeology Conference (REARC) in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, in 2016, she immediately saw the work practiced by attendees at the conference as public history, or in many cases, public pre-history or public archaeology. In reconstructing her view to include the work presented at REARC, she has expanded her definition of public history to include these fields. In 2017, she returned to the REARC conference to address these potential collaborations, and outline ways in which archaeologists and public historians can work together to make their research and projects accessible to local communities or a general public.

Experimental archaeology is by definition a participatory and experiential learning experience for all involved. Many attendees at REARC work with museums or other public organizations to gather data, educate the public, or otherwise engage with the past and people. The author’s own work in museums demonstrates the connections among public history, experimental archaeology, and various theories of learning, both in an academic setting and informally.

Elaine Davis, in How Students Understand the Past, explains that to understand how to teach history (or for our purposes, pre-history) one must know how the past is constructed in the minds of individuals, who are shaped in turn by their age, culture, ethnicity, and other factors (2005, p.17). She argues that historical knowledge is constructed in two ways: narrative understanding and logical-scientific understanding. The former is perhaps the most important to the processing of this new information in the learners’ minds, while the latter is generally the kind of learning that takes place in the traditional academic space or a classroom. To stimulate informal learning, such as that which takes place at museums, archaeological sites, or historic places, Davis argued for active engagement, with tangible objects such as original artefacts or replicas to help a learner connect to the past on a personal level. By using interactive and object-based learning, learners are more engaged and connected in studies of the past (Davis 2005, p.115). Wineburg’s Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (2001, p.14) addresses many reasons about why people study history, such as what history can teach us about humanity and ourselves, how history should be taught, and what exactly history’s place is outside of the classroom. Wineburg argued that through historical study and thinking, students can create a development of feelings of kinship and relationship to people in the past that we study (2001, pp.3-21). A general movement towards learning about humanity and social history has been evident in the past several years, and many museums are adapting this model. A session at the Tennessee Association for Museums in March 2011 focused completely on telling the stories of people who lived in the past and their personal documents and pictures. Using these primary sources, curators told the history of Tennessee through people rather than “facts and dates.” This is a natural space for experimental archaeologists or public archaeologists to occupy, as well.

Many visitors to museums or educational organisations engaged in informal education or public history are motivated to learn, but when faced with paying an admission fee or choosing between an educational experience or an entertainment event, community members often choose the entertainment opportunity instead. Wineburg asked how educators can incorporate more experiential learning into traditional education courses (2001, p.14). The concept of “edutainment” that has been discussed in museum classes and conferences in the past ten years is only one solution to motivating students or the general public to learn (Lepouras and Vassilakis 2005, pp.729-736 and Zancanaro, Stock and Alfaro, 2005). Creating educational and entertaining programs is still somewhat controversial; are public historians and experimental archaeologists entertaining or educating our public? At the same time, as long as people are engaged and actually learning, are the precise methods important? If edutainment can happen in museums and institutions of informal learning, perhaps more people can be motivated to learn about history and critical thinking.

Experiential learning, in the author’s experience, is a natural fit for many museums and historic spaces. The C.H. Nash Archaeological Museum at Chucalissa in Memphis, Tennessee, embodies experiential learning, both for graduate students from the University of Memphis as well as the public. Students in museum studies, archaeology, anthropology, and history converged at the archaeological site of Mississippian Native Americans to produce exhibits, educational programs, and experiences for visitors.

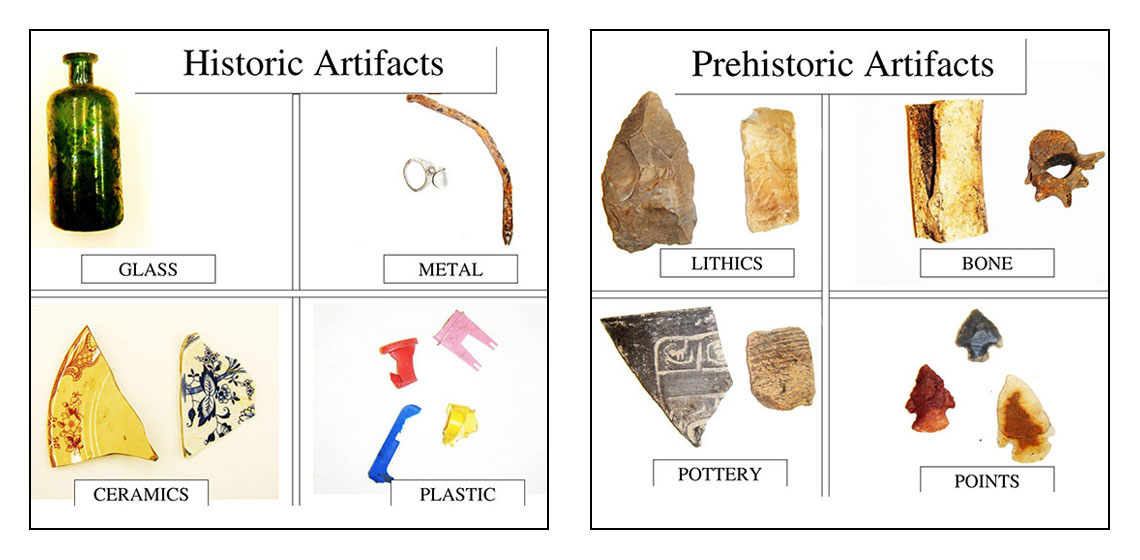

One such program is the “Mystery Box” educational offering; the program offered visitors or students the opportunity to “excavate” various materials. Upon arrival at the museum, visitors are divided into small groups to analyse their assigned box of artifacts. Museum staff present a brief program on the nature of historic and prehistoric artifacts, how archaeologists conduct their work, the role of the museum in the system of processing artefacts, and the relevance of this exercise to the visitors’ own lives. Participants then sort through genuine, unprovenanced artifacts, such as lithics, nails, coins, glass bottles, and more from the museum’s educational collection. Then, the participant assesses the objects’ purpose, age, and value to the historical and pre-historical narratives. A discussion of historical versus pre-historical, as defined in relation to the pre-Colonial territory that is today the United States, is also included. The tactile connection with the past stimulates the learner’s need to touch the past and explore the purpose of various everyday objects, while contemplating what future historians or archaeologists would say about the items they leave behind.

Living history is another natural fit for participatory or experiential learning, and one that works well at historic sites and landscapes. The author has worked at various historic house museums that worked with living history professionals to demonstrate candle making, quilting, butter-churning and more; however the real impact on learning and comprehension seemed to appear when visitors or volunteers were engaged in that work as demonstrators to other visitors. The aspects of dress, play, and “going back in time” engage the learner in a way that cannot be as easily emulated in a traditional classroom. At the Tower of London in London, England, the author observed a living history event in which educators butchered, cooked, and ate a stag. While interesting, the lack of participatory engagement by the public left the program somewhat lacking in impact. One must always consider safety and health issues when working on these programs, which is the likely explanation for this barrier at an otherwise incredible historic space.

One of the pioneers of living history has also hosted the REARC conference for the past few years, Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, USA. The reconstructed eighteenth century village began as one of the most successful “edutainment” destinations for American history. Visitors can explore historic houses, talk with brick makers about the process of forming and firing bricks, take a carriage ride with an authentically dressed guide, participate in the daily mustering of the troops, and more. Students who attend the REARC conference experience all of this, but then also participate in the experiments with both Colonial Williamsburg staff and REARC participants and professors. At REARC, students have built fires, thrown darts with atlatls, skinned and tanned hides, and even helped in metal smelting. This had a great impact on the students and the research questions of professors, but, as a public historian, the author was most impressed with the inclusion of the general public who visited Colonial Williamsburg during the conference. In 2017, the atlatl dart throwing seemed to be the most popular amongst both general visitors and REARC students. This applied history in the public sphere educates everyone involved in lifestyles of the past and offers public historians and experimental archaeologists the opportunity to gather more data and engage the public.

One of the most popular events with students at the author’s university is the community archaeological Volunteer Day at a local site. Students and volunteers, with little to no archaeological experience, are invited to try their hand at excavating, under the careful eye of professional archaeologists and professors. This gives participants who may not otherwise have the opportunity to engage with artifacts a chance to engage in the field of archaeology, object analysis, and historical narrative building.

These public spaces seem a perfect complement for experimental archaeology, archaeology, and experiential learning. Elements of these programs could be translated into primary and secondary education, as well as post-secondary classrooms, open-air museums, or experiments conducted with public input. While this partnership is still in its infancy, partnership and collaboration should lead to some interesting and educational opportunities for professional practitioners and community members alike.

In addition to the participatory elements of programs that allow people to learn, enjoy, and understand history or archaeology, co-creation through collaboration and contributory exhibits or programs are yet another way public historians and experimental archaeologists can work together to engage the public in a mutually beneficial system. One of the best ways to incorporate a contributory or co-created program is by allowing volunteers or visitors to serve as participants in the making of an exhibit or research projects.

Dr. Robert Connolly, an archaeologist and museum professional who previously served as the Director of the C.H. Nash Museum and as professor to students who worked at the site, has highlighted the possibilities which museums, especially archaeological sites, offer to the public and scholars. Citing information found in Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum (Simon, 2010), Connolly and his co-author Tate (2011, pp.325-345) describe ways in which museums and professionals in interdisciplinary fields can engage the public as volunteers or visitors through contributory, collaborative or co-creative processes.

Contributory experiences at museums or with the public are a limited engagement technique that provides an opportunity for the public to provide feedback or examples of their own experiences. A popular example of a contributory exhibit at a museum is a space for visitors to answer a question related to their experience, or the exhibit and include it in a portion of the exhibit. At the Blount Mansion historic house museum in Knoxville, Tennessee, visitors were asked to reflect on their own education in comparison to the education of people on the United States Frontier in the eighteenth century. They could submit their contribution either on a Post-it note, which became a part of the exhibit and later an accessioned collection item, or as a temporary contribution on a chalk slate similar to those used by students in the eighteenth century.

While contributory experiences are a great start to the inclusion of the public in the creation of history, exhibits, or experiments, Connolly and Tate (2011) also argue that collaborative and co-created experiences have a larger impact on everyone. Involving the public in a more impactful way, through shared authority and creation, offers the opportunity for stakeholders to become more involved and invested in the event. Incorporating their personal experiences and needs results in a more valuable learning experience.

All of these examples of experiential and participatory education techniques can be incorporated into the work of experimental archaeologists and public historians. Though many in these fields already approach their work with these procedures in mind, it is worth remembering that in most cases the work is for the greater good of the public. Connolly (2012) pointed out that “participatory experiences aid in demonstrating the relevance of cultural heritage to the public. Whether in museums, government, or academic institutions, we function as public servants. As professionals, we are all on the public dole one way or the other. We must be accountable and demonstrate our relevance to the public we serve”. The fields of public history and experimental archaeology should continue to pursue partnerships and collaboration amongst practitioners to better engage and educate public audiences. Through these collaborations, professionals will not only add to their data and informational catalogs, but they will also inspire new partners, potential donors, and stakeholders to care for and engage with the past.

Keywords

Country

- USA

Bibliography

Connolly, R. and Tate, N., 2011. Volunteers and Collections as Viewed from the Museum Mission Statement. Collections, 7, 3, pp.325-345.

Connolly, R., 2012. Contributory, Collaborative, and Co-Creative Experiences. Available at: https://katiestringerclary.com/2012/... [Accessed on 15 January 2018].

Davis, E., 2005. How Students Understand the Past: From Theory to Practice. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Lepouras, G. and Vassilakis, C., 2005. Virtual museums for all: employing game technology for edutainment. Virtual Reality, 8, pp.96–106;

National Council on Public History (NCPH). What Is Public History? National Council on Public History [online]. Available at: http://ncph.org/... [Accessed on 16 January 2018].

Simon, N., 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

Weible, R., 2008. Defining Public History: Is It Possible? Is It Necessary? The newsmagazine of the American Historical Association: Perspectives on History, [online]. Available at: https://www.historians.org/... [Accessed on 25 February 2018].

Wineburg, S., 2001. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Zancanaro, M., Stock O. and Alfaro I., 2003. Using Cinematic Techniques in a Multimedia Museum Guide, Museums and the Web 2003. Charlotte, North Carolina, 19-22 March 2003.