The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Indian Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes to Archaeological Content in History Textbooks

History is a record of past events, activities, situations, and processes. As a subject, it helps students in understanding not only who they are and where they came from, but it also offers them an opportunity to make informed decisions about present issues and future developments. History also teaches responsible citizenship, and develops critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Historians believe that the study of history sensitizes an individual to the universality of the human experience as well as to the peculiarities that distinguish cultures and societies from one another (Daniels, 1981; Voss, 1998). As one of the disciplines among social sciences, history, thus, represents accounts of multi-layered and multifaceted human experiences across time and space constructed by historians through working on both primary and secondary sources.

Introduction

It is well accepted that using real evidence/primary sources is an important criterion in the teaching and learning of history. The focus in classrooms in many parts of the world has already moved to using both primary and secondary sources instead of solely using school textbooks, which has made the teaching and learning of history much more useful, joyful, and productive. Archaeological remains form one of the most important of primary sources. Use of archaeological evidence to present the past lives of people broadens the mental horizons of learners and exposes them to the validity and viability of different lifestyles (Fedorak, 1994, p.26). Archaeological remains not only speak of the lives of the elite few, but also present the stories of ordinary people and their daily exploits.

Today it is observed that historical resources are vulnerable. Historical sites are destroyed in many different ways, from intentional vandalism to casually uninformed surface collection by the public. Most people are unaware of the great scientific value that is contained within one potsherd on the surface of a historical site; that artefact may be the only key to identifying the people who were there, and if casually collected that knowledge is lost forever. It is a common knowledge that the more people are ‘aware’ about archaeology and the work of archaeologists, and the more they appreciate cultural heritage, the more monuments and archaeological sites and objects will be saved from destruction or robbing. Peter Stone has rightly pointed out in Corbishley that …“Misuse and abuse of the physical heritage can never be stamped out fully by legislation, but only by raising the level of awareness of the general public through education. One of the most important influential forces on the public today is their children-themselves the general public of tomorrow…” (Stone, 1985, cited in Corbishley, 2011, pp.84-85).

Importance and use of archaeology in history classrooms

Young students often face difficulty in understanding the concepts of time and history. Use of material or archaeological remains gives students tangible evidence that can help them in conceptualizing the passage of time (Kissock, 1987, cited in Fedorak, 1994, p.26). Archaeological evidence is also considered ideal for making students understand the concept of change because by observing and working with artefacts from the past that reflect change through time it becomes easy for students to understand how changes take place through time (ibid., p.26). In The educational value of archaeology, Henson, Bodley and Hayworth have pointed out that “teaching using archaeological evidence has many positive educational benefits for history in schools. Archaeology is a hands-on experience. Investigating artefacts and monuments engages students with the physicality of the past in a way that cannot easily be matched by documents alone. Archaeology easily lends itself to interactive and investigative teaching” (2006, p.36).

There are many published researches on the utilization of archaeology in the classroom. In 2003, Levstik, Henderson and Schlarb presented the paper Digging for Clues: An Archaeological Exploration of Historical Cognition, an investigation into the effects of archaeology education on student learning. Their conclusion was that archaeology education units can contribute to students learning goals in history, archaeology, and respect of archaeological ethics. In 2003 Dr. Mary Derbish conducted an investigation into effects of archaeological units on students in her classroom. Her research results showed an increased knowledge of and appreciation for archaeology, but little increase in student awareness or concern about archaeological ethics (Derbish, 2003, p.108). The Society for American Archaeology (SAA) in its study entitled Exploring Public Perceptions and Attitudes About Archaeology concluded that “the American public’s knowledge of archaeology and what archaeologists do is neither solid nor clear and it includes misconceptions about the field of study” (Ramos and Duganne, 2000, p.30). Such studies indicate that early archaeological education is needed. SAA outlines that, “Archaeology offers students an opportunity to use and develop such critical thinking skills as observation, interpretation, deduction, inference, and classification. It also enhances students' skills in mathematics (e.g. working with grids), science (e.g., studying stratigraphy), language arts (e.g. taking notes), and art (e.g., drawing objects)” (Society for American Archaeology 1995, p.1). Matt Glendinning (2005) in his paper Digging into history: Authentic learning through archaeology, came to the conclusion that archaeology is an effective way to study history-collaborative, multidisciplinary, experiential, fun and a perfect vehicle for learning how to learn the past.

The use of archaeological and historical evidence is now firmly part of the way history teachers teach their subject in many countries. A number of archaeological organisations and museums in many countries are working to encourage teachers to include archaeology and the study of evidence in learning in schools (Corbishley, 2011 pp.83-84, 94). Workshops are also offered to educators in various places, such as the Archaeology, Ethics, and Character workshops offered in Utah (Moe, et al., 2002, p.112) which are trying to bring archaeology into the classroom. Research shows a good level of awareness and enthusiasm for using buildings and local places in teaching and that they provide good opportunities for cross-curricular work (Corbishley, 2011, p.96). Many universities offer teachers courses in archaeology.

Archaeology in Indian school curriculum frameworks

In India broad guidelines regarding content and process of education at different stages of school education are formulated by the national government. These guidelines are further elaborated by the National Council of Educational Research and Training1 (NCERT) in the form of curriculum frameworks. So far four curriculum frameworks have been prepared by NCERT. These frameworks talk about archaeology in terms of cultural heritage (which includes both archaeological and living heritage). The curricular recommendations are further introduced through syllabi and textbooks at different stages.

The syllabi and textbooks prepared by NCERT in India is generally adopted or adapted by states and other school systems. However, since education comes under ‘concurrent list’ many states prepare their own syllabi and textbooks.

Since the very beginning of the development of textbooks at NCERT, the use of archaeological evidence has been introduced within the history curriculum in an infused-integrated way. Prior to 2005, the history textbooks included photographs and drawings of objects, sites, and maps along with the content describing the life and activities of the people who made these artefacts. But such illustrations were very few and were used to illustrate rather than as evidence. It was to be a long time before sources of evidence were presented. Students had to wait until 2005 for the introduction of carefully chosen pictorial resources with extended captions or classroom activity and discussion based on an archaeological or historical ‘source’.

School education in India has undergone important changes in 2005 with the introduction of the new National Curriculum Framework (NCF)and its emphasis on providing opportunities for child-centred learning; boost the scope of activity-based learning, for example learning by doing (NCERT, 2005). The curriculum in history prepared following the NCF really differs from the previous ones. The history textbooks now present evidence based history. Evidence in textbooks is often referred to by the authors as ‘sources’ or ‘pictures’ and is now presented to students, in the form of facsimile documents, quotations and photographs of buildings and objects and they are encouraged to reach their own conclusions by questioning the evidence. The use of archaeological and historical evidence like photographs, paintings, plans and artist’s impressions, each with detailed captions, is now an integral part of the history textbooks. There is now a different approach to illustrations in history textbooks. They no longer just break up the text or try to make the book more attractive. Now students are required ‘to do’ history, not merely receive it. They are to learn about the human past by looking at the sources, both primary and secondary, which historians use when they tell the story or the history of the past.

So archaeological evidence was very much part of the history curriculum since the onset but was presented in such a way that teachers themselves often did not know that it was contained in the curricula that they were required to teach. After the NCF what finally emerged as a new key feature of history textbooks is the introduction of historical sources which are presented to students to study, think about and reach conclusions by themselves.

Need and justification of the study

As archaeologists’ world over nowadays are striving to share information with the students and public in general about archaeology and seeking their support in protecting and identifying archaeological resources, it is important to understand what our students know, perceive, and feel about these pressing and important issues. It has been learnt in various teacher training programmes and in interaction with students that students are very keen to know more about archaeology but do not have enough exposure to this field of study. Research to investigate the use and impact of archaeology on students’ historical thinking in India is missing. Though there have been some efforts to probe the history teaching in general. Raina (1992) conducted a survey of history teaching in the state of Rajasthan. While Dahiya (2003) conducted a survey of teachers of CBSE affiliated schools in the states of Haryana and Delhi on the importance of archaeology in teaching secondary students ancient and medieval history. Department of Education in Social Sciences, NCERT (2004) did an evaluation study of Social Science, Language and Commerce textbooks but nowhere has there been an effort to understand the exposure, knowledge and interest level of students about archaeology or the impact of archaeological material in textbooks or evidence based teaching on students’ historical thinking.

Research questions

The study attempts to answer the following research questions:

- Whether the history curriculum develops students’ understanding about archaeology.

- Whether the history curriculum across the board promotes sensitivity towards preservation of cultural heritage.

- Whether the teaching-learning process adopted in schools motivate students of history to pursue a career in archaeology.

Objectives of the study

In response to the research questions, the objectives of the study are:

- To understand the perceptions, knowledge and attitudes about archaeology amongst higher secondary students of history in schools affiliated to different boards.

- To ascertain the views of teachers, archaeologists and other stakeholders on the use/relevance of archaeology in school and how its knowledge in school can contribute towards a better understanding of this subject in higher education and pursuing a career in this area.

- To assess the challenges in teaching archaeology to students.

- To examine the possibility of further coverage to archaeology in school curriculum or introducing this as an elective subject.

Sampling procedure

The sample for the study was purposively drawn from schools affiliated to Central Board of Secondary Education2 (CBSE), Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations3 (CISCE) and Uttar Pradesh Board of High School and Intermediate Education4 (U.P. Board) where History is taught as an optional subject at higher secondary stage. Fifty schools were randomly selected for the survey. One Postgraduate Teacher (PGT) of History in each of the selected schools participated in the study as respondents of the questionnaire. Of the fifty selected schools, thirteen schools were randomly chosen for Focus Group Discussions (FGD) with students.

Method of procedure

Review of syllabus and textbooks

The syllabi of history for classes XI and XII used in CBSE5 , CISCE and the U.P. Board were reviewed to discover the rationale and objectives of history teaching and coverage and the organization of archaeological content and projects in these boards at higher secondary stage. History textbooks were reviewed in terms of content, questions/exercises and visuals to determine how content on archaeological materials in these textbooks contribute towards a better understanding of history and a basic understanding of archaeology among students and to what extent these textbooks sensitize students towards the preservation of cultural heritage.

Tools used

- Questionnaire for PGTs in History

A questionnaire was designed to ascertain the views of teachers on different aspects of teaching of history such as: the use and relevance of archaeology in school, how its knowledge in school contributes towards a better understanding of history in higher classes, pursue a career in this area, challenges in teaching archaeology to students and the possibility of more coverage of archaeology in the school curriculum or introducing this subject as an elective subject. - Focus Group Discussions with students

The FGD was conducted with students to determine whether the history curriculum develops their understanding about archaeology, promotes sensitivity towards cultural heritage, whether the ability of teaching-learning process adopted in schools in motivating students to pursue a career in archaeology and the possibility of more coverage to archaeology in school curriculum or introducing archaeology as an elective subject. Thirteen higher secondary schools were randomly identified for FGD with students. Of these schools, five were affiliated to CBSE, four to U.P. Board and four to the CISCE Board.

The duration of each FGD was around 35 minutes. For this five students from class XI and XII each were identified by the subject teachers. If the school was a co-education school, equal number of girls and boys (2+3 or 3+2 from each class) were selected. - Semi-structured interview schedule for experts

The experts included teachers from university, field archaeologists, museum experts, heritage and conservation experts whose views were sought to obtain an insight into their efforts in promoting awareness towards cultural heritage.

Data collection procedures

The field work started in January 2017 and ended in March 2017. Prior to school visits, permissions were sought from KendriyaVidyalayaSangthan6 (KVS), JawaharNavodayaVidyalayas7 (JNV), CISCE and office of Joint Director, Education, Meerut region (U.P.) for schools in Delhi and National Capital Region (NCR) region, respectively. Subsequently, the headmaster/principal of each sample school was contacted through telephone and were informed about the investigator's visit to the school.

Questionnaire for PGTs in History

A detailed questionnaire on various aspects of history teaching was given to teachers teaching history at higher secondary stage. They were requested to fill in the details and return it through post or email (as scanned copy) to the investigator within a week or 10 days of the visit. 50 teachers participated in the study.

Focus Group Discussion

Students from Classes XI-XII (around 100) participated in the discussion. Views of students were recorded on notebooks and some were finalised on the same day after the school visit. In the beginning, during a few visits it was noticed that despite requests to conduct FGDs only with students some teachers were present in the room and were trying to influence students in answering certain questions. Later, principals were requested to instruct teachers to follow our suggestion. Students required time to be forthcoming with their views.

Semi-structured interview with experts

Views and opinions of 10 experts were sought which include university teachers, archaeologists, museum, heritage and conservation experts. Date of the interviews were fixed with prior permission given over phone or email.

Analysis and justification

Mixed methods were used to analyse qualitative and quantitative information gathered from students and teachers.

- Quantitative

Data collected in the form of 1-5 point Likert scales were entered using Microsoft excel software for data analysis. - Qualitative

A variety of qualitative information was collected through review of syllabi and textbooks across school boards, open ended questions for teachers and focus group discussions with students. These were recorded and analysed manually. Triangulation was used to pool together information from various schools.

Findings and discussion

Syllabus and textbooks across boards

History is part of Social Science until Class X and in Classes XI-XII history is available as an optional subject. Schools affiliated to CBSE follow a syllabus and textbooks prepared by NCERT, while the other two boards just prepare a syllabus and give flexibility to affiliated schools to follow textbooks published by private publishers. Unlike CISCE and UP, the NCERT syllabus provides detailed rationale and objectives not only at the beginning of the topics but also provides objectives along with all topics. Review of syllabi and textbooks broadly revealed that while CBSE and UP Board teach ancient, medieval and modern Indian history at higher secondary stage, the CISCE Board teaches these time periods in classes IX-X, so for comparative analysis, their syllabi and textbooks for classes IX and X were also reviewed along with their syllabi for classes XI-XII which deals with modern Indian and world history.

Rationale and objectives of teaching of history at higher secondary stage

The History syllabus was reviewed to find out the rationale and objectives of history teaching in terms of coverage and organisation of archaeology related materials and projects in these boards was at a higher secondary stage.

The first objective of the NCERT syllabus is to foster creative engagement of the students with the subject. Therefore, the syllabus has been devised in such a way that it helps students to develop a historical sensibility as well as awareness of the significance of history and not merely look at it as a set of facts about the past. The second objective of the syllabus is to reduce the load on students. This has been accomplished by focusing on important issues and events. By achieving the goal of load reduction, the syllabus as its third objective expects that it will allow teachers adequate time to dwell on every single theme in factual detail with conceptual depth. Fourthly, the syllabus has sought to widen the scope of historical inquiry/study. Within this context, the syllabus while integrating the major curricular concerns of teaching the subject, has also lent adequate focus on the history of the marginal groups and the issues of gender. Finally, as the syllabus addresses the curricular concerns of interdisciplinarity, it has also sought to include a range of themes that demonstrate connectivity between disciplines and thereby helps to broaden the idea of history.

At the higher secondary stage, for example classes XI and XII, the syllabus has adopted an issue-based approach to devise and promote historical understanding of themes that span across time and space. Therefore, it has taken care to introduce the students to the idea that historical knowledge develops through debates and that sources have to be carefully read and interpreted.

In Class XII, the syllabus likewise introduces the students to components of ancient, medieval and modern Indian history with an objective to deal with a set of core themes that allows the students to learn about each theme in greater detail and depth. The Class XII syllabus is formulated in such a way that each chapter becomes an exploration of one particular kind of source: archaeological remains, inscriptions, epics, chronicles, religious texts, travel accounts, government reports, revenue manuals, police records, newspapers, buildings, paintings, illustrations, advertisements and oral sources.

CISCE syllabus does not provide the detailed rationale or objectives behind teaching history. At the secondary stage the syllabus aims to enrich the understanding of those aspects of Indian historical development which are crucial to the understanding of contemporary India, to invoke a desirable understanding in pupils of the various streams which have contributed to the development and growth of the Indian nation and its civilization and culture, along with the development of a world historical perspective of the contributions made by various cultures to the total heritage of mankind (CISCE Syllabus,2014, p.1).

At higher secondary stage, the syllabus aims to provide learners:

- with accurate knowledge of significant events and personalities of the period under study, in sequence and in context,

- familiarize with factual evidence upon which explanations or judgments about the period must be founded,

- the development of an understanding of the existence of problems and relevance of evidence of explanations,

- the development of the capacity to marshal facts and evaluate evidence and to discuss issues from a historical point of view,

- the development of the capacity to read historical views in the light of new evidence or new interpretation of evidence,

- to foster a sense of historical continuity,

- encourage diminution of prejudices and to develop a more international approach to world history,

- the development of the ability to express views and arguments clearly using correct terminology of the subject,

- and familiarize the learner with various types of historical evidence and to provide some awareness of the problems involved in evaluating different kinds of source materials.

At secondary stage the Class IX syllabus comprises of ancient Indian history from Harappan civilization to Gupta period, medieval Indian history of South India, Delhi Sultanate, Mughal history and some important events of world history, i.e the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Industrial revolution. Whereas the Class X syllabus largely deals with the Indian freedom struggle from 1857 to 1947 and some topics relating to world history. The syllabus at the secondary stage lists out topics and sub-topics along with the mention of different kinds of sources e.g. literary and archaeology in every chapter. The syllabi of Classes XI and XII covers the history of nationalism (from swadeshi movement to civil disobedience) and some topics from world history. Although the syllabus doesn't mention anything about developing historical sensibility among students, it lists topics and sub-topics which mention different sources e.g. literary and archaeological with every chapter. This indicates that syllabi makers do consider imparting basic understanding of various sources to students. The syllabus for Classes XI-XII though is in the form of topics and sub-topics only, although at the start it focuses not only on the knowledge aspect but also on development of various abilities through working on sources as important objectives of the syllabus.

We have taken one state board for example Uttar Pradesh (UP)8 for the study. In Uttar Pradesh a few secondary schools are being governed by the CISCE and the CBSE boards, but most of the secondary schools are affiliated to the U.P. Board. The syllabi for all the stages of school education and textbooks till Class VIII are being prepared by the government agency but Class IX onwards schools are free to choose textbooks written by different authors on the syllabus prepared by the state. The focus of the syllabus as has been delineated in its syllabus document is, to see Indian history in the context of the world history, to focus on student’s originality while assessing them and to motivate students to acquire understanding from latest historical researches. Considering the importance of historical visits, the syllabus recommends, to make such visits compulsory and suggests that students should go on these visits at least once a year. The syllabus makes it very clear that the study of history should be based on the past of the whole nation so that students can acquire knowledge about the culture of their forefathers, their achievements, take inspiration from them, and not repeat their mistakes. It aims to make students aware of those facts which helped in developing feelings of nationalism and also understand those shortcomings which posed a threat to this and not repeat the same or protest against those shortcomings. The syllabus as its objective wants to develop feelings of universal brotherhood, humanistic and realistic attitudes among students. It suggests to build an understanding of the present based on its past and suggests to understand the international course of events and their impacts on our nation. Maps and pictures are used to make history interesting to the learners.

In Class XI the syllabus in history focuses on sources of history, ancient Indian past from prehistory to Gupta dynasty and medieval history from sultanate to Sufi saints and in Class XII topics such as Indian history from Mughals until the independence of India in 1947 are taught. The syllabus is in the form of topics and sub-topics only. The UP syllabus does not say anything about historian’s craft or how students are expected to consider different sources and acquire skills associated with this discipline.

Unlike CISCE and UP, the CBSE syllabus provides detailed rationale and objectives not only at the beginning of the topics but also provides objectives along with all topics. Both UP and ICSE syllabi give importance to students’ historical visits. While the UP suggests to make visits somewhat compulsory, the ICSE puts visits as one among many project works/assignments in Classes IX, XI & XII.

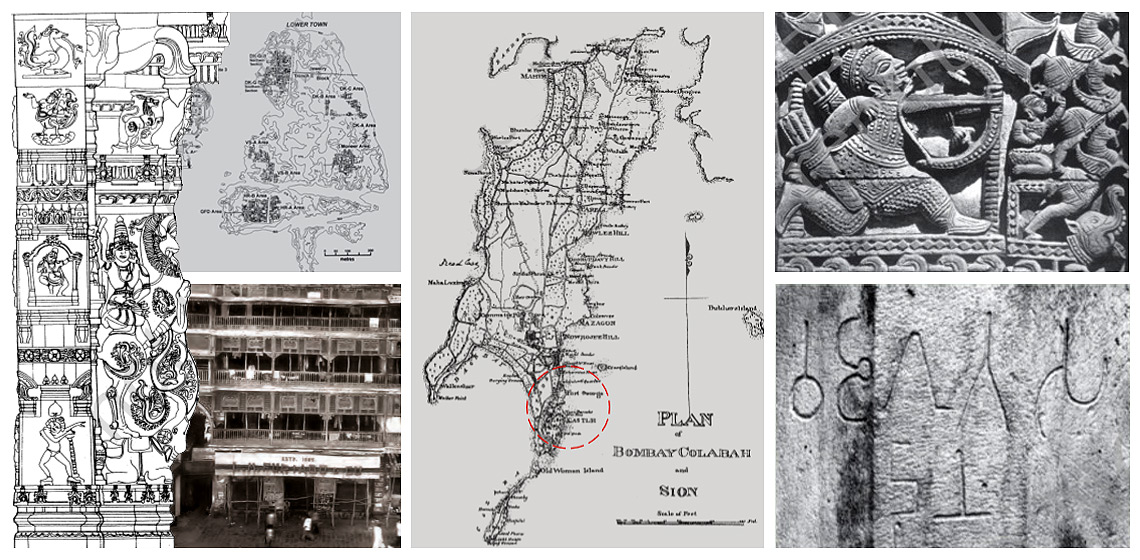

Comparison of textbooks of different school boards in India

Since the study sought to find out the perception of teachers and students about archaeology or archaeological content in their history textbooks, an effort was made to compare these textbooks with each other in terms of content, visuals and exercises. The investigator tried to see how and to what extent these textbooks motivate students through exercises/activities or content towards the preservation of material remains or heritage. While comparing textbooks the investigator took the broadest possible view of archaeology, which encompasses all the physical evidence for the whole of history of all the peoples of the world, from human’s earliest appearance right up to today. The physical evidence for archaeology includes, of course, movable objects as well as sites, monuments and landscapes.

Content

The NCERT textbooks bear testimony to the objectives that the syllabus set out to achieve. These textbooks present evidence based history wherein students are required ‘to do’ history, not merely receive it. Students learn about the human past by looking at the sources, both primary and secondary, which historians use when they talk about history.

These textbooks are based on a thematic approach with emphasis on different kinds of sources for understanding the past; archaeological sources are one. These textbooks provide whole content that has been interwoven with archaeological materials rather than general archaeological information. The textbooks provide content and context from primary sources, from which the students obtain an all-encompassing view of the archaeological periods and ancient societies. Archaeological works completed by archaeologists and discussions on various archaeological sites form important aspects in different chapters. Various terms relating to material remains/archaeology have been explained in these textbooks like archaeobotanist, archaeozoologist, excavation, artefact, archaeological evidence, coins, seals and inscriptions to name but a few.

The textbooks in history for Class XI Themes in World History informs students of early ancient societies of the world like Ancient Mesopotamia, Africa, Iraq, Roman empire, Middle East lands, Europe, North America and many others. The content of the textbook tries to highlight the changes that took place with space and time. Class XII textbook titled Themes in Indian history has three parts and each part deals with ancient, medieval and modern periods of Indian history respectively.

The CISCE board does not prescribe any textbook and gives flexibility to schools. The investigator found that in the CISCE schools Longman History and Civics published by Pearson is one of the most popular textbooks for Classes IX-X. Whereas, for Classes XI-XII Modern India and World History textbook by Kalyani publications is the most available and used textbook. Class IX textbook which deals with ancient and medieval Indian history presents a detailed chronological narrative of these periods with colourful visuals of artefacts and sites. Class X textbook’s focus is on modern Indian history and some topics from world history. This book, too, provides a chronological history of these time periods with great factual detail and lots of visuals of various sculptures, buildings and paintings. The chapters have key points, a ‘did you know’ section providing some additional information, a ‘find out’ section which tells just to find out some more information, and key terms and exercises. As far as textbooks for Classes XI-XII are concerned, these deal with traditional topics like development in the economy, industrialization, revolutionary character of the society, various uprisings et cetera. The world history part mainly talks about crisis, changes, political movements, political dominance, wars, revolutions et cetera.

In these books different time periods have been elaborated on with all their various aspects - dynasties, rulers, society, economy, art architecture and many more topics. The sources are often mentioned in the beginning while introducing the topic. Unlike the NCERT these books do not present content interwoven with material remains but have content on material remains/archaeology often in a segregated way. The content in the CISCE textbook is plain chronological narrative organized in an old fashion often focusing on key points and providing information in bullet points. This can be illustrated through example of content on mahajanapadas in these two set of textbooks. Both textbooks have content on mahajanapadas but while the NCERT textbook talk of how mahajanapadas came into being and what were their features, the CISCE textbook just focuses on specific janapadas, their rulers, administration et cetera. Buildings of Brahmosamaj and some others are mentioned in these CISCE books but their studies revolve around their establishment only. The NCERT content is interactive and raises thought provoking questions for students to ponder and reflect on. There are questions appended to various sources also which motivate students to learn and understand the content with the help of material remains and not limit him/her to information about some archaeological sources of the time only. For example, questions like how has the king been portrayed on the coins? What are the elements in the sculpture that suggest that this is an image of a king? So there is an effort throughout the NCERT textbooks to encourage students to critically reflect on and analyse the content.

The syllabus document of the U.P. clearly mentions that no textbook has been prescribed or suggested by the board and that school principals in consultation with their subject teacher can choose the textbook as per the syllabus. In the U.P., textbooks till Class VIII are prepared by government agency and Class IX onwards, textbooks of different publications are available where schools are free to make selection. These textbooks have been written following the syllabus prepared by the U.P. Board. For research purposes, the investigator talked to teachers from different parts of the U.P. and found out about three most popular publications being used in the UP schools. These are Rajlaxmi publications, Vidya publications and Hindi Pracharak publications. All of these textbooks have identical features. These books mainly present content in the form of long chronological narratives full of factual details and give detailed information on various material remains excavated from different sites and coins, inscriptions, tomb, mosques, forts and other buildings. These books provide details on different rulers, economy, polity, society and administration during different dynasties. It can be regarded as cliché or as a traditional form of presenting a lesson which has been followed over the years in many books all over India. While dealing with modern history, the book also mentions various buildings like the oriental college in Aligarh, Hindu college in Kolkata, Brahmosamaj, Arya samaj, Prarthanasamaj, cellular jail but these have not been discussed from the point of view of architecture. An important feature of these books is the viewpoints or statements of different historians or archaeologists that are provided in all the chapters. Another important aspect of the U.P. books is that at the end of each book there are different types of appendices on the important dates, personalities, maps and historical places. Of these the appendix on important historical places focuses on places of historical importance with their present location and details of materials excavated and found from there. These brief write ups about each such place provide information about art architecture, sculpture and sometimes about museums at these places and their respective collections.

The NCERT books make an effort to focus on the art and architecture of India and tell about the history it contains. Along with discussing this aspect in different chapters it discusses this physical or tangible heritage in great detail in a separate chapter also. On the other hand, other books have dealt with these arts related contents while discussing the rule of a particular empire or ruler when they were built. The NCERT book points out the efforts of foreign officials and Indians in conserving the material remains. Discovery of artefacts, their migration to London, discussion on Asiatic society and perspectives of British archaeologists are important contents of the NCERT textbooks. Various examples of art and architecture with lots of visuals and discussions on different architectural styles followed in south India, north India and western India in the construction of temples give students a sound understanding of artistic excellence of India. Apart from this, the lesson also gives details of how art history is perceived in India. In all, the NCERT textbooks, archaeological remains whether they are in the form of artefact, excavated material or other tangible proofs like ruins of palaces, buildings from all periods of Indian history are discussed and illustrated. Besides, it also has maps, lay out of various cities and plans of various buildings and line drawings of various architectural and sculptural features. So the presentation of the content in all NCERT textbooks which combines archaeological finds with literary and oral traditions, monuments, inscriptions and other records help students to understand history in a better way.

Questions/exercises

As far as questions given in the NCERT textbooks are concerned, the chapters have different kinds of questions like short answer, long answer, questions on visuals, map work, project work which expect students to visit museums or some historical monument or site and prepare a report of the visit. These questions focus on comparison and contrast, summarising, listing, writing brief write ups, discussion, reasoning, interpretation, analysis and exploration. For inquisitive and passionate students, suggestive readings and links are also given for further knowledge.

As far as the CISCE textbooks are concerned, Class IX-X textbooks have short answer, structured questions and one source-based question. An interesting feature of these books is the source based/picture study question where a picture of an image, artefact, inscription, coin, seal, or painting has been given with three to four questions. This has its advantages, as it introduces students to various types of primary sources used in the study of history and encourages them to analyse these resources. But unlike NCERT these questions are mostly knowledge based like in one of the chapters they have asked students to study a picture of a temple and then instead of asking students to observe architectural features and identify it, students are asked where is the temple is located, who constructed it, which deity is this temple located et cetera. In structured questions they have provided some points on which students need to answer. These questions focus on factual details only and are mainly knowledge based. At higher secondary stage both short and long answer questions are given but these call for factual details only. The exercises in general are information oriented with very few questions focusing on ‘why’ and ‘how’.

Questions given in the U.P. textbooks are generally of three kinds: short answer type, long answer type, multiple choice questions and sometimes one question on mapping historical places, routes, places of attack and the extent of empire. Barring very few questions where students are asked to evaluate, other questions are knowledge based only. No publication has questions on visuals or other kinds of sources.

Visuals

Visuals play an important role in forming the imagination of a student. As far as the NCERT books are concerned, visuals given in these books are very clear, colourful and large with detailed captions. Visuals include pictures of coins, sculpture, inscription, temples, mosques and dargahs, sites, various art forms, palaces, buildings, layout of cities, plan of buildings, line drawings of architectural and sculptural features, maps, artefacts and other material remains. These textbooks even have visuals of the processes and techniques involved in tool making which make it very easy for a student to imagine the time.

CISCE Classes IX-X textbooks have visuals which are small but quite clear and colourful. Though not all but some visuals ask students to find out more about the visual. Classes XI-XII textbooks have very few visuals and they are of various personalities with some maps. These visuals are in black and white and are not of very good quality. The textbooks do not provide any visuals of sites or places related to different events and incidents.

There are very few visuals given in all publications books of the U.P. Board and the visuals that are presented are not clear and colourful.

Teachers’ and students’ perceptions about history teaching objectives

The preferences of teachers for history teaching objectives are in line with the currently accepted objectives of the subject. The statement relating to the acquisition of various kinds of skills is the most favoured objective. In other words, this group views history to be a purely intellectual pursuit which, in terms of its outcomes, is more related to the development of skills such as information gathering and presenting one’s viewpoint more rationally. Similarly, a statement like “history helps us to know only about the past” is the least favoured statement with the teachers. This indicates teachers’ unanimity with historians that history is not just the study of the past. This is also an indicator of the change in traditional viewpoint of history that the teachers used to hold previously that history means the study of the past only. But surprisingly this viewpoint is not shared by the students. Almost all students shared that they like history because it tells them how our society evolved, what happened in the past, how people used to live in the past, insight into the contemporary world and that the same mistakes are not committed again et cetera. The students’ understanding of history is that it is related to the past.

Teachers’ and students’ perception about archaeology and its coverage in history textbooks

The perceptions of teachers about archaeology and its coverage in history textbooks are concerned mainly with its study of past human cultures from investigation of their material remains, investigating artefacts, and monuments and sites brings the past alive in a way that texts do not. Archaeology offers students an opportunity to use and develop critical thinking skills such as observation, interpretation, deduction, inference, and classification. Archaeology should be given more coverage within the history curriculum. This reveals that across school boards, the teachers’ levels of understanding about archaeology is fairly broad and accurate. This preference is possibly guided by the current approach of making use of archaeological materials in teaching.

CBSE and CISCE students found the content and the visual presentation of history books satisfactory and they appreciated those chapters which focus on archaeological remains, art and architecture of the time and showed broad awareness with words like ‘archaeology’ and ‘archaeologist’. Students from U.P. schools also liked the chapters on Harappa, art and architecture of the period for discussion on different findings, though these books lack in visuals. Students from some of U.P. schools had some idea of archaeological sources, but they did not have any idea of what an ‘archaeologist’ is and they also said that their textbooks don't help them in understanding these. Most students in U.P. schools did not know anything about these terms, though these topics have been discussed in their textbooks.

On the contrary, teachers do not have a favourable view of history textbooks in providing sufficient interactive content, visuals, questions and activities on archaeological evidence. NCERT history textbooks include photographs and drawings of objects, sites, and maps along with the content describing the life and activities of the people who made these artefacts whereas textbooks used in CISCE and UP schools largely lack on this aspect, but surprisingly there is only slight difference in observation of teachers from CBSE who are a bit less dissatisfied than the other two boards. Perhaps, content, visuals and questions on archaeological material given in history books have not penetrated into their psyche as an important source of understanding history and they continue to look at the narrative given in general sufficient for teaching of history. Statements like “teaching with archaeology requires various resources like actual objects et cetera” received low preference. The findings reveal that these teachers view archaeology in terms of actual objects of the period only and they are still not able to make use of resources available locally for this.

However, views of teachers and students were also sought on whether they want archaeology as an elective subject or interweaved within existing textbooks but with more coverage. To this most of all of the teachers and students, except one expert, responded by saying that they want more of such material, but it should be imparted within history and not as an elective subject and the focus should be on evidence based teaching of history.

Instructional strategies used by teachers

The findings of the study reveal that “questioning” and “assignment “are the two main instructional strategies used frequently by the teachers. This observation is in tune with the students’ views on projects/activities. Barring JNV students almost all students from the CBSE affiliated schools, whether government or private, reported that they prepare project files. Like JNV, UP schools also do not conduct any activity in the class or prepare any project file. However, one UP school students shared that they do some projects which are mostly written- some on rulers, some on art, architecture and different types of primary sources. They also shared that they find these activities interesting for their understanding of the topic. This was probably the result of individual teachers’ efforts.

CISCE school students responded that they prepare project files on the topics suggested by their teacher and are guided by their teachers before they start preparing the project. It was observed that in the name of ‘assignment’, schools mainly require students to prepare project files which is a routine activity and students have no say in selection of topics. Most of the time students are just given the topics to prepare projects without proper guidance and once these are submitted there is literally no sharing or discussion in the classroom.

Discovery/inquiry-based learning and use of primary sources are rarely used by the teachers. These teachers though, consider use of real evidence/primary source an important criterion in teaching history. The teachers also admit that it is one of the most engaging ways to develop and support students’ higher order thinking skills. The teachers wish for more content on material remains in their textbooks but they rarely make use of the strategies of discovery/inquiry-based learning and use of primary sources. Considering different kinds of primary sources are important for understanding history, experts expressed displeasure over negligible use of these sources in history classrooms. According to them one probable reason could be non-exposure to source/evidence-based teaching which forbids teachers from using it in their teaching.

A similar case exists regarding ‘visits to historical places’, which teachers want to be made compulsory but very few of them, as reported, use this strategy. It is well accepted that visits to historical places are of utmost importance to history teaching. No teacher from the UP school reported to take students on visits. The situation with other schools affiliated to CBSE and CISCE is not far better either. Some teachers from these boards reported field trips while others did not. However, while replying to open ended question on whether the teachers take their students for visits to historical monuments/sites/museums, half of the teachers said ‘yes’ and half of the total said ‘no’. To another question on listing 3 such visits conducted in the past 3 years, very few teachers could mention some such places. Conducting visits/tours to historical places needs proper teacher motivation and training. One would have expected that these teachers would at least take their students for visits to historical places of local importance. This observation is shared by students also. Barring one private school, almost all of the students reported that they are never taken on such visits. Although they reported of going on such visits with family and friends and termed their experience of such visits ‘real learning’ as it provided 3D view of the monument, a real feeling of touch, see and first-hand experience. An informal discussion with some of the responding teachers elicited the information that they are not able to take students for visits to places of local importance because of lack of financial and administrative (safety, security responsibility of students) support from their school heads. Lack of physical facilities, financial and other resources and lack of training are mainly the reasons put forth by teachers for not making use of different instructional strategies listed in the questionnaire.

Instructional media used by teachers

The most frequently used instructional media by these teachers is ‘textbook’, followed by the use of chalkboard and maps. Again, there is a difference between the use of the textbook (all 50 teachers) and the chalkboard (44 teachers), versus the use of map (38 teachers).One thing that emerges very clearly from the study is the lack of using important teaching tools such as a field trip, primary sources, smart board, slides, films and computer. These tool or teaching aids help to provide “substitute” experiences in place of first-hand experiences. In terms of learning, there is almost total unanimity amongst psychologists that experiences such as these have much greater impact than the “symbolic” experiences which are provided only through listening (narration) and reading (textbook). History teaching becomes lively, interesting and meaningful through the use of audio-visual media such as slides and films which, unfortunately, this group of teachers has reported that they had almost never made use of. However, while replying to the open ended question on sharing their views with regard to challenges that they face as a history teacher and share ways/methods that they adopt to deal with these challenges they said that they try to employ different teaching methods and tools (maps, charts, questions or quiz, ICT, field trips) to arouse the students’ interest. But while reporting this they admitted that due to lack of time and the vast syllabus it is not easy to make use of above mentioned methods and tools frequently and are thus forced to limit their teaching to explanation of the topic and asking questions only. This observation is in tune with the views of students who reported that their history classrooms are really boring where reading from textbook and explanation provided by teachers predominates. Most of the teachers reported lack of infrastructure and other resources, non-availability of different audio-visual aids/material and lack of finance for the purchase, of such material.

Awareness about cultural heritage

With regard to awareness about cultural heritage it was observed that though students appreciate chapters which talk about tangible remains and heritage, most of them lack awareness about cultural heritage. Experts from universities and other stakeholders were unanimous in commenting that students today lack an awareness of our culture and lack sensitivity towards our cultural heritage. Only a few students indicated their awareness with words like ‘cultural heritage’. The pre-service and in-service teacher training programmes are basically lecture oriented. Teachers do not get hands on experience to work with different kinds of sources. It was observed that the ASI conducts drawing, debate, photo exhibition, essay competitions on some occasions. Along with heritage week and International heritage day celebrations for students and sometimes teacher training (on request) but these programmes are not organised on regular basis. The experts from the museum too shared that they conduct in-service training for museum professionals only and there are some tailor made programmes for the public and occasionally for out of school children but they do not conduct any programme for the general teachers.

Perception towards history as a subject and career options

It seems teachers themselves do not have a favourable view of history or students who opt for taking history. Almost all teachers reported that very few students opt for history out of interest. Many times students who did not score well in their previous class opt for history at higher secondary stage so students opting for history are not academically very bright. There is almost total unanimity amongst people in general and teachers in particular that a major in history can only lead to either teaching in schools or universities. The students are not aware of various career options as they have never been exposed towards these options. Most of the students shared that their schools have career counselling sessions in Classes X and XII but these are held for science students only. It was observed that humanities students are equally keen for knowing various courses and career options in their subjects but neither the teachers nor the school system helps them. This is a common problem across all school boards and types of schools. This deters students from pursuing this subject at a higher level.

Conclusion and Implications

Syllabus and textbooks

There is a wide gap observed in the CISCE, UP and CBSE syllabi and textbooks in terms of content and coverage of archaeological remains. Every board need not to follow the CBSE syllabus and textbooks. There is a worldwide change in the teaching of subjects such as history whereby there is consideration of evidence/source based teaching and attainment of various critical thinking skills. There is a need for all of the school boards, whether private or state, to examine their syllabi and textbooks thoughtfully and bridge this learning/knowledge gap while keeping in mind the grade level capabilities of the students and the objectives of teaching history. Textbooks need to follow the broad objectives set out in the syllabus. Having more content and visuals on archaeological remains interwoven with the whole content, coupled with activity based teaching and field visits, will ensure that students gain a real historical knowledge and attain skill sets to apply the learned knowledge and skills not only within schools but in societal day to day life external to the schools. Teaching and learning of history achieved in such a way will help students becoming increasingly aware of and sensitive towards cultural heritage and ultimately encourage them to protect it.

Teacher training

Teachers, both in pre-service and in-service training programmes, need to be trained in the same kind of teaching/learning strategies and methods which they are expected to practice with students. If students are to learn history by “doing it” then the teacher must develop the capability of “doing it” also. The training should not merely focus on lecture and narrations but rather teachers should be given help with teaching physical evidence which they are often not taught about in teacher training programmes. Awareness of various courses and career possibilities in the subject should also form one of the important aspects of both the pre-service and in-service teacher training. There is a need to have such programmes regularly for teachers of all school boards.

Support materials (Print and electronic)

The success of a teacher is dependent upon the availability of adequate and qualitatively sound resources such as textbooks, maps, timelines, various types of audio-visual materials, the models of important sculptures and architectural pieces and other archaeological remains. Replicas and models require only the cost of their production, and its expenditure might be borne by the Government. These objects can be supplied free of charge to all secondary schools and the teachers of history should be trained and advised to make fullest use of them. Nowadays the educational potential of the modern technology is widely acknowledged, although their actual use in formal educational contexts is under-utilized. This should be considered as an added value, given that their use could foster not only knowledge and competencies relating to the specific domain (for example, history and cultural heritage), but also the development of various ‘higher order’ skills.

Visits to historical places

Visits play an important role in helping students experience our culture first-hand, which not only gives students a sense of wonder but also makes them curious to know more about the past connected to it. It helps the students construct history through observation and develops their observation skills and aesthetic sensibilities and instils an appreciation of elements of architecture and our cultural heritage. It is therefore recommended that, in the syllabus prescribed for history, excursions and visits to excavated sites or places of historical significance be made compulsory, and exercises relating to these visits be incorporated into student assessment.

Career counselling sessions

It is suggested to generate interest among students towards history through engaging and interesting ways of teaching-learning, expose them to various facets of history, organise career counselling sessions with experts so that students can know that as a student of history they can study archaeology, art history, museology, conservation, heritage management, epigraphy, numismatics et cetera and can attain a career in these areas and related sectors. Furthermore, careers are possible in ASI, state archaeology departments, universities or work as private volunteers or archival collectors, curators, writing of history books, contributions to journals and publications. For these, consecrated efforts are required from all stakeholders.

Collaboration among stakeholders

Though ASI and various museums do organise a few programmes to make students aware and sensitive towards cultural heritage, these are meagre, irregular and isolated efforts and are not equivalent to having a student population who is aware of its cultural heritage and is sensitive for its upkeep. Connections should be made among different networks relating to archaeology, museums, heritage, conservation and school education. Archaeologists, heritage managers and other stakeholders must understand what teachers’ do, including the methods of teaching and learning and the curricula or textbook’s available to the teachers. If archaeologists and heritage professionals are to influence classroom teachers, they should treat them as professionals. The professionals should listen to the teachers, engage with them in instituting educational programmes and in the production of teaching and learning resources. Archaeologists should consider including education programmes in all archaeological projects. There is a need to forge partnerships among curriculum developers, school functionaries, parents and other stakeholders in this regard.

- 1The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is an autonomous organisation set up in 1961 by the Government of India to assist and advise the Central and State Governments on policies and programmes for qualitative improvement in school education. The major objectives of the NCERT and its constituent units are to: • undertake, promote and coordinate research in areas related to school education; • prepare and publish model textbooks, supplementary material, newsletters, journals and develop educational kits, multimedia digital materials, etc. and organise pre-service and in-service training of teachers; • develop and disseminate innovative educational techniques and practices; collaborate and network with state educational departments, universities, NGOs and other educational institutions; • act as a clearing house for ideas and information in matters related to school education; and act as a nodal agency for achieving the goals of universalisation of Elementary Education. In addition to research, development, training, extension, publication and dissemination activities, the NCERT is an implementation agency for bilateral cultural exchange programmes with other countries in the field of school education. The NCERT also interacts and works in collaboration with the international organisations, visiting foreign delegations and offers various training facilities to educational personnel from developing countries. Retrieved from http://ncert.nic.in/about_ncert.html

- 2The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) is a national level board of education in India for public and private schools, controlled and managed by Union Government of India. More than twenty thousand schools in India and around two hundred and twenty schools in almost 28 foreign countries are affiliated to the CBSE. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Board_of_Secondary_Education

- 3The Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE) is a private national level board of school education in India that conducts the Indian School Certificate examinations for Class XII. More than two thousand schools in India and abroad are affiliated to the CISCE. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/.../Council_for_the_Indian_School_Certificate_Examinations

- 4U.P. Board of High School and Intermediate Education was the first Board set up in India in 1921. This is Asia’s largest board in terms of number of students. This board is administered by the largest state (in terms of population) of India, Uttar Pradesh.

- 5The NCERT syllabi and textbooks are prescribed in schools affiliated to CBSE, so for convenience NCERT/CBSE have been used interchangeably while dealing with syllabi and textbooks in the whole paper.

- 6The KendriyaVidyalayaSangthan (KVS) refers to a system of Central Government Schools in India that are instituted under the aegis of the Ministry of Human Resource and Development.It is one of world’s largest chain of schools.

- 7Jawahar NavodayaVidyalayas (JNV) are alternate schools for talented students in India, which are fully residential and co-educational established to find talented children in rural areas of India and provide them with an education equivalent to the best residential school system.

- 8Uttar Pradesh is a state in the northern part of India and it is the most populous state of India.

Keywords

Country

- India

Bibliography

Corbishley, M., 2011.Pinning down the past: archaeology, heritage, and education today. Volume 5. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer Ltd.

Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations, 2014. Syllabus for classes IX and X.[online] Available at<https://cisce.org/pdf/ICSE-Class-X-Syllabus-Year-2014/9.HISTORY.pdf>[Ac… 28/03/2016]

Dahiya, N., 2003. A case for archaeology informal school curricula in India. In: B.L. Molyneaux and P.G. Stone, eds. The Presented Past: Heritage, Museums and Education London. Routledge. pp.299-315.

Daniels, R.V., 1981. Studying history: How and why. Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Prentice Hall.

Derbish, M., 2003. "That's How You Find Out How Real Archaeologists Work—When You Do it Yourself": Children's Experiences with Archaeology. M.A. College of William and Mary.

Fedorak, S.A., 1994. Is Archaeology Relevant? An Examination of the Roles of Archaeology in Education. (Doctoral dissertation, M.A. University of Saskatchewan.

Glendinning, M., 2005. Digging into history: Authentic learning through archaeology. The History Teacher, 38(2), pp.209–223.

Henson, D., Bodley, A. and Heyworth, M., 2006. The educational value of Archaeology. In: J.C. Marquet, C. Pathy-Barker and C. Cohen, eds. Archaeology and Education: from primary school to university, British Archaeological Reports International Series (BAR S) 1505: 35–39.

Levstik, L.S., Henderson, A.G. and Schlarb, J.S.,2004. Digging for Clues: An Archaeological Exploration of Historical Cognition. In: Ashby, R., Gordon, P. and Lee, P., eds. Understanding History. London. Routledge, pp. 46–60

Moe, J.M., Coleman, C., Fink, K. and Krejs, K., 2002. Archaeology, ethics, and character: Using our cultural heritage to teach citizenship. The Social Studies, 93(3), pp.109–112.

National Council of Educational Research & Training, 2004. Rational and Empirical Evaluation of NCERT Textbooks (Languages, Social Sciences and Commerce), Unpublished Report, New Delhi: NCERT.

National Council of Educational Research & Training, 2005. National Curriculum Framework. New Delhi: NCERT.

Raina, V.K., 1992.The Realities of Teaching History, National Council of Educational Research and Training, New Delhi.

Ramos, M. and Duganne, D., 2000. Exploring public perceptions and attitudes about archaeology. Rochester, NY: Harris Interactive.

Society for American Archaeology, 1995.Guidelines for the Evaluation of Archaeology Education Materials. Public Education Committee, Formal Education Subcommittee. Bureau of Reclamation, Denver.

Voss, J. F. (1998). Issues in the learning of history. Issues in Education, 4(2), 163-210.