The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

Experience instead of Event: Changes in Open-Air Museums Post-Coronavirus

An EXARC 'call to arms' to reevaluate and develop your Open-Air Museum's interpretation strategy

The year 2020 started out for museums as usual, with plans for new exhibitions, new buildings even, and above all many events and visitors. Soon we saw how wrong we were. Open-air museums who had prepared to open up for the season found out that COVID-19 meant they were sitting ducks: no visitors, no income, no life in the museum area. The situation will not return to 'normal', we will have to think again about everything we were used to in our work. This article is an EXARC 'call to arms' to reevaluate and develop your Open-Air Museum's interpretation strategy.

Part 1

Challenging Times

The Coronavirus crisis which is hitting the world with such force can be a game changer for museums, and especially open-air museums holding good cards. Old ideas which were left on the shelf for later, suddenly catch momentum and are deployed much sooner and on a much wider scale than expected (The Economist, 2020). The crisis amplifies the situation: healthy museums will come out of this stronger. They will re-invent themselves by implementing their core strengths and the unique qualities of archaeological open-air museums of personal contact, multi-sensory impact, interaction on every knowledge level, wide-ranging educational methodologies, practical hands-on opportunities, being outdoors, and live historical personal interpretation, to create a new balance in their heritage interpretive mix (Tilkin, 2016). What has become more important in these COVID-19 times is first of all to be a safe space, but even more importantly, we argue, it is to look critically at your programming, your interaction and entertainment for all ages and your museum’s suitability for individual visits and small groups. Do not stop at implementing your safety measures but follow through with strategies to enable your museum to adjust to a very changed society.

Very understandably, the world seems to stick to a kind of protective mind set which comes up after the initial shock of mandatory museum closing and first reopening dates within sight. But unfortunately it seems this fight or flight response has an inherent nostalgic longing for things to be as they were before the Coronavirus crisis and we are not yet ready or able to understand the need for change. Pre-virus modus operandi are unquestioned and unscrutinised, they again form our goal and benchmark for the future in the sense that everything again will be all right and we will restore past situations and formats. The Coronavirus crisis, however, has provided a chance to reshuffle our cards, design tailor-made solutions and actually re-invent ourselves, based on our core strengths and unique selling points as archaeological open-air museums. EXARC strongly encourages archaeological open-air museums to re-evaluate past modus operandi on all levels and to reformulate benchmarks for success and operational goals to gain a better fit to the new societal changes.

Museums suffering from understaffing, slim finances and weak online presence will not be able to adapt fast enough. The Dutch Museum Association estimated on April 9 that 25% of their museums will go bankrupt before the end of 2020 (Museumvereniging, 2020), and this could very well be the case for archaeological open-air museums worldwide.

COVID-19 is the biggest global challenge humanity has faced for generations that will not be solved by a simple lockdown of the world for over just a few months. Basic hygiene and social distancing rules will probably be in place for years to come and large gatherings will not be possible for a long time. Our festival and event culture will change.

The effects of this pandemic will be traceable for years to come. An important measure is social distancing, where people are advised to keep a distance of for example 1.5 metre from each other. In the Netherlands, this has already been dubbed “the 1.5 metre society”. Like all other organisations, museums must define how they would be able to serve the people again, based on this requirement or else they will not be able to reopen. For indoor museums, that may sound easy in theory: each room can only host a maximum number of people. This was already defined by fire regulations but now will be for other reasons as well and the maximum number will probably go down drastically. In historical buildings, this can create problems, additionally because routing through the museum will become more controlled (one-way movement).

This article does not deal with the position of museum staff in Coronavirus times. This is another complicated matter which is different in each country, depending on local or regional variations. Often there are important differences, even within a single museum, for example between employees and freelancers. Other colleagues such as International Museum Theatre Alliance (IMTAL) are perhaps picking up those challenges for freelance historic interpretive staff.

Developments in Target Groups

Our open-air museums showcase the daily life of the past; something different from classic history lessons where often the elite is highlighted. Therefore our visitors’ profile mirrors society more than in many other museums. We have always seen more families with children than in showcase museums; the threshold to visiting our open-air areas is lower than elsewhere. Museums cannot afford to cherry-pick certain “easy” target groups anymore; they will need to cater for all visitors who are coming in after the Coronavirus lockdown. We will, for example, see a rise in individual visits, as people will feel safer to be on their own (or travel through life alone), but who do crave social interaction. An open-air museum could provide this through their live historic interpretations.

We may have to place a maximum number on the amount of tickets which can be sold every day; people will need to plan ahead – and for that, there are technical solutions.

Museums will need to focus more on visitors from nearby. This is not only about local school groups, but also about the excursionist or same-day visitor who returns home. Overnight tourism will drop substantially; the only visitors from abroad will be special interest tourists or peer groups, depending on the timeframe when borders are re-opened. This means both the programming and communication strategy of the museum needs to reflect these changes.

Educational Groups

One of our core audiences, educational groups, will be able to start operating again soon. School groups visiting open-air museums will probably remain customers and these local groups will become very important and your first group visitors. But stop, think and check: Is their expectation of a museum visit the same as before? Or, could programming be adjusted to facilitate the current needs to fill the gaps that home education has left, or for example split-classroom education? Education officers and schoolteachers should team up to adapt the programmes to make them meaningful, but above all safe experiences. An important issue is transport to the museums. Are schools able to get there safely, can they use public transport again, are parents allowed to drive with children of different families in one car or does the school need multiple coaches (which they may not be able to afford)? Or will museums be more used by local schools which can rely on alternatives, like individual transport to the museums? Museums will need to concentrate on these schools first, and possibly offer them options of returning regularly throughout the year. Museums should contact local schools to get first-hand information from them and closely plan new series of visits to cater to their needs. Ideally, a museum will already have an advisory group of schoolteachers, but if not this is a good time to create one.

Regarding the practicalities of school visits, many things are controlled: the number of people, the time span they visit, the program, and the space which they are allowed to use. In some cases, museum buildings designed to hold a full school class cannot be used as such anymore due to the reality of space required for social distancing. School visits must be more controlled than in the past: activities will need to be adjusted and children will have to remain under control more than previously, when they could run through the museum for a certain time. A solution may be to close the museum for regular visitors at certain time as not to overlap with school groups. This non-parallel programming is especially important for senior citizens, which form an ever larger part of the museum visitors.

Personal contact between museum staff and children is an issue. Even if museum staff can blindly execute their educational programmes, we now need to look at these from another perspective, to spot the adjustments we need to make in the new 1.5 metre society. The educational delivery will become harder due to the physical distance. The number of children per education officer will go down, and each smaller group will need more space than previously, if available at all. Possibly, a group visit to a museum will become a luxury.

In order not to disturb the authentic overall ‘picture’ an archaeological open-air museum would like to portray, hygienic facilities for handwashing or toilets are not usually a formal part of the reconstructions. This needs to be more prominently incorporated and not just situated near the exit of the museum, as is standard practice and the legacy of measures taken during the Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD).

Adjustments on Tourist Visits and Programming of Large Events

But what to do with tourist visits, events like a Celtic festival or a knight’s tournament which used to attract thousands of visitors? Open-air museums have to earn a larger part of their annual turnover than traditional museums do. The latter often receive a larger part of their budget in annual funding, whereas the priority of some open-air museums is to earn money to survive. Events however, are a strange element in museums: often more money is made on beer and sausages than on entrance fees. Here, the core activity is not mediation of knowledge, but offering leisure with a touch of culture. The Coronavirus crisis teaches us to step away from financially risky events on which one has grown too dependent. It is better to spread everything: the risk, the people and the activities. Museums must treasure experience above event again, and thinking of the UN Sustainable Development Goals: we need to adapt to using resources responsibly. Whether this is about staff, finances, plans, animals and ecology in general, and even if we talk about travelling, ecological footprint or waste management. Our Museums need to become more sustainable, and our answer to the Coronavirus crisis is part of this.

As a current dilemma for example, The Viking Museum Haithabu (Germany, https://haithabu.de) cannot reschedule their large Viking Event ‘Summer market Haithabu’ outside the tourist season in a similar way; should we hold on to pre-Coronavirus formats or invent new ones? Local guidelines on hosting events will change as well, so it is not just the choice only of a museum itself.

Part 2

Towards a Paradigm Shift: Experience instead of Event

If we move away from larger events and spread the activity and the risk, this will lead to a calendar of events, where every weekend, every holiday, something is happening – nothing large and spectacular, but rather smaller, meaningful and interesting. This way, potential visitors can expect there is always life in the museum. This may be just as expensive as a large event, but it is better to have 10 days with 200 visitors each instead of one day with 2,000. The activities presented can be led by a single person, demonstrating an activity, or doing living history.

Does our seasonal opening change? Yes, the off-peak season will become more important: we do not want a high spike in visitors and activities, but want to spread that over more weeks and months. But as always, we are dependent on tourist income and peak moments. Perhaps open-air museums will not have standard closing months (deep in winter or in high summer, with possibilities for new activities depending on the season), but will have to be open as much as possible, to gain those extra visitors which are trickling in. This may lead to an increase in or new distribution of existing staffing – multiple small events which would possibly require more staff rotations.

This will also mean that the better-prepared museums diversify their approach as to minimise the risk: they have both an indoor and an outdoor area, they are strong online as well as in their own regional society (restaurants, other museums) and have craft courses or lecture series to attract various visitor flows. Finally, they have a good connection with the local population and personal relations to schoolboards and special interest visitor groups.

A way to generate small scale personal experiences is the construction of a new, say, medieval house, to be watched and enjoyed by the visitors. Guédelon in France is a good example of a site where the core activity is exactly this (https://www.guedelon.fr). One could also have a low entrance fee, but for an extra experience (like shooting with a bow and arrow, baking a pancake) the visitor pays a bit extra on the spot. |

Using the Unique Selling Points of Archaeological Open-Air Museums

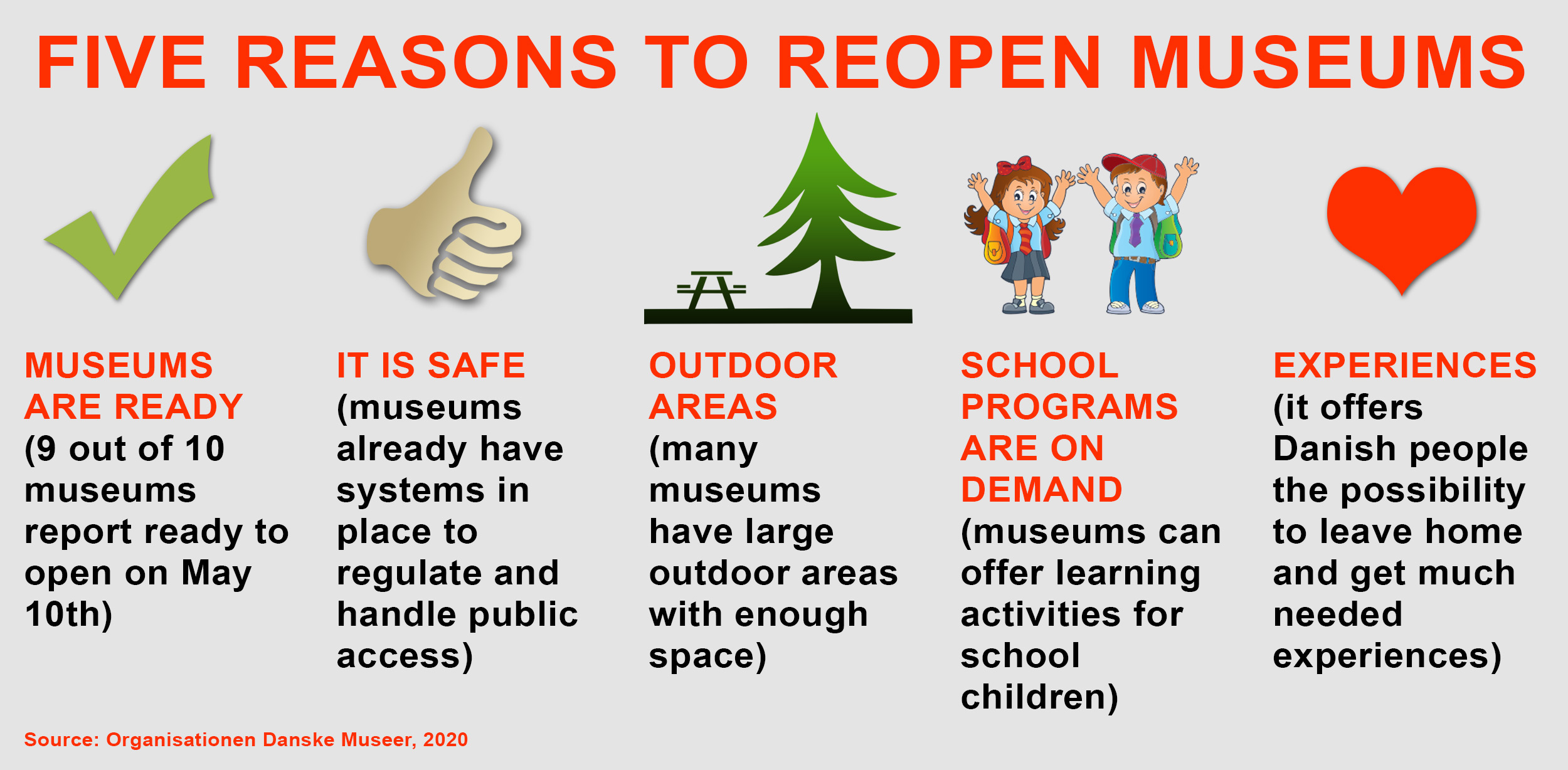

In archaeological open-air museums, the fun part of the visit is always linked with a lesson to take home. However, to be able to go out and to have a new and valuable experience in a safe controlled environment may temporarily become more important than the informal learning experience. Certainly, Risk Assessments that follow standards and guidance provided by the local authority will be needed to convince local authorities that a museum can open safely again. Or there are National Decrees such as by the Dutch Museum Association one has to adhere to, even if you are not officially a member, but mandatory when you use the term museum to denote yourself. But the focus should be back to meaningful interaction soon. Interactions between the visitor and the museum as well as between visitors in their own groups.

Bringing the story, teaching the public, helping to learn from the past, that is what museums are for. COVID-19 forces our museums to refocus on their concept, their mission and vision, and step away from the daily madness: why do we exist, what is our task? This will lead to changed emphases of how we undertake our tasks. Our priority is to offer a higher quality experience, relevant to our visitors. It is now all about survival and adapting to the situation as smoothly as possible. And the ones who are able to look further than the scramble to be visible online.

For open-air museums, there are challenges, but also great opportunities due to our existing strengths. The future lies not so much in quantity, but in quality. We will see more small scale experience offered instead of larger events. The very small museums that are managed by volunteers often know the public personally, and therefore can easily control the flow. Medium size open-air museums (between 10,000 and 75,000 visitors per year) have probably solved a lot of safety issues by making a few practical changes only. However, the museums with the higher visitor numbers (75,000+) will need to adapt the most in order to survive. They should question if they will be able to reach the visitor numbers they previously had, at all. At best, this will only be the case in about five years from now.

In any crisis, one should think of one’s own unique selling points to respond in the best possible way. Are you better with education? What are the advantages of the open-air surrounding to social distancing? Isn’t our personal service an important asset? We offer layered information, tailor-made to the visitor. This personal approach can take many shapes in post-Coronavirus times. Several museums offer workshops in ancient technology, for example casting bronze swords or making bows. These are held via registration, meaning the museum controls the activity, and it can be postponed if not enough people register. How do we find a new post-Coronavirus balance between activities taking place and their attendance?

Interpreters and Educators in the Museum

Can we rely on operating and staffing our new programming as before? The position of silver generation volunteers will change dramatically. Where previously a volunteer (senior, retired) would play an active role in handling visitors, the museum’s responsibility towards this has changed dramatically. This category of volunteers is especially at risk from the virus and should be shielded. This means that permanent staff who would normally work from the office to design programmes and train people, will now have to return to the work floor and deliver these programmes first-hand.

Another option, especially good for the holiday season or weekends is to have a group of actors or volunteers camp in the museum and simply show the daily life of the Middle Ages for example. Costs for the museum are relatively low, but it does include a bit of training and guidance from the museum to the actors to raise quality and educational standards. It is of course happening already, but the Coronavirus crisis is an opportunity to improve. What is clear from many social media posts by re-enactors (or living historians) is what they miss most: their friends, the atmosphere, the campfire and drinks together, but they do not mention generally that they are missing the interaction with the public. Photos posted reflect how they look in their kit, almost no interactions are depicted. Their priority in being present in a museum again will be self-centred, not focused per se on educating the public. Museums need to be aware of this and make sure there is ample visitor interaction and demonstration, and keep the balance more so than before.

Programming Experience Design and Visitor Flow

The generic themes will off course remain the same (Vikings, Knights, et cetera) but interaction will increase because the public will demand more. Visitors are willing to pay more for a safe and comfortable quality experience (c.f. Pine and Gillmore, 1999). The programming will be less linear across the day, but may run several smaller loops, within certain time slots. However, a visitor does not want to feel rushed or be checked because they take longer to enjoy the experience. Another practical technique to control visitor flow is layering: an event is carried out by a few main actors, the background is filled by people who are less active with the public or, if you have a circular programming, with activities which occur in loops of about one hour. This system of using timeslots influences a lot more things for the visitor, such as using the restaurant facilities, or the planning of a show at a specific time. It should feel like a well-made tour when one is guided past all interesting spots in a good flow and provide the feeling that there is time to take that extra photo, discover something, ask that question - all of that within an hour, before the next group arrives.

One should for example witness baking bread and also have the chance to see the result emerging from the oven and get to taste it. It is the museum’s responsibility that everything fits, that it is well orchestrated and needs are met. The museums must communicate to the visitor the added values of working this way. Only those museums who know exactly how and why their visitors behave, and are able to influence this will be able to adjust their programming and wayfinding accordingly.

Managing Expectations & Planning Ahead

A successful visit to a museum is a return ticket to an experience (paraphrased from Hansen, 1972: “En vellykket rejse er en returbillet til en erfaring”); a museum visit is the creation of a memory for the visitor to cherish. A positive experience is important in a world where personal recommendations in the own personal network are very valuable to create this new local focus and bond with the museum in post-Coronavirus lockdown.

The museum on the other hand, wants the visitor to take something home from their visit, a lesson learned, but also an experience shared together with the people who are visiting. In the hunt for special experiences, museums should not seek to emphasise exclusiveness too much. Each experience in itself is authentic and unique. Open-air museums are in essence about inclusiveness.

The museum should manage the expectations of the visitors and communicate clearly that there is always a simple experience to be had there – not spectacular, but meaningful and therefore valuable. Managing expectations means that communication should be correct and one should never under-deliver. This means, if a program is advertised, it should go ahead as presented, even with just a small number of visitors present. Programming is not just about when there is an audience, it is also about getting that public to return on a future visit. In this way, a solid reputation can be built where visitors trust the museum in otherwise uncertain times. It also develops a shift in perception of the museum, from being only interesting to visit during large events and extraordinary programming due to ever enlarging superlatives, to revaluing the basic programming and personal contact, which results in a more mindful experience.

Mindful museum Visits

Mindfulness as a concept is gaining a new, less hippy-like meaning. Planning ahead is one aspect of that; being more receptive to the visitor’s wishes and educational needs is another. This means, our museums will have to fall back on their experience and be more flexible. If everybody understands the logic of what measures are required in order to function safely in the wake of this Coronavirus pandemic, not everything has to be caught in rigid rules. Digital solutions can help with this flexibility, for example publishing variable opening times on the museum’s website, booking tickets and a timeslot for the visit online, so the museum knows beforehand how many interpreters to plan/ programme on site and can monitor the amount of visitors. A website is no longer a static publication of the folder of seasonal events; it requires updating on a regular, short-term basis and almost instantly answering visitor questions. It may serve to show a video of your entrance area and hygienic facilities to set visitors, parents and teacher’s minds at ease (eg. site access for visitors) as is often provided for special needs visitors. It is important to reinstate a sense of security and safety, and implement the required mitigation measures set out in risk assessments. Once these are satisfactorily adhered to, there is opportunity for content and meaningful interaction programming, reflecting Maslov’s ‘Hierarchy of Needs’ projected on a museum visit. This aspect of reassuring visitors that it is safe to do visit will be challenging and clear communication, for example via a ‘Safe to Visit’ logo and pay-off in all your communication, will be important to inform and communicate about visitor opportunities.

Going Digital In the current era, museums need to position themselves digitally, or people are unable to find you. Younger generations are less likely to pick up the telephone to ask you a question, information is sought out through social media and a search engine, which preferably leads to your website, but more often does not! Most people under 50 will have their first encounter with museums online; actual visits may happen later. Going digital does not replace the real experience but enhances it. With digital options, a museum reaches out to its potential public and picks them up where they are, aiming to convince them to come to the museum itself or enjoy the museum in the virtual world. A whole new realm of opportunities opens the moment a museum provides its main information in a digital format. Some examples are collected at https://exarc.net/virtual-events. Not only can research be done by more people more easily (think open access), 3D models of houses can be published using platforms such as Sketchfab or Matterport, annotated with layers of information. The same information from the basic dataset can be tailored to different audiences, just by tweaking the outcome or form in which they are presented. In this way the personal approach which is so important in our museums is not lost. Games can be developed following an existing exhibition which takes please in real life, for example. All of these digital options are ways to execute a very important task of museums without social or hygienic risks to either the visitors or the museum personnel. However, we need to keep in mind that now that for example children receive more formal education via their computer screens, they will be less willing to consume digital content in their leisure time. Going digital does not replace the real visit, but both options should coexist to create the best visitor and audience reach. |

What can EXARC do?

Not only is society facing a paradigm shift, but so are our EXARC members. We are here to help you to reinvent yourselves.

The first step should of course be the Health and Safety regulations that will need to be put into place to allow the reopening of your museum. After this initial phase, we strongly argue that you rethink your programming, interpretation mix and visitor formats to be able to cater for a prolonged period of years where large gatherings are not possible and it is no longer manageable to hold on to pre-Coronavirus event and activity formats.

We propose creating a re-opening checklist for archaeological open-air museums, including advice and thoughts. We welcome your suggestions and will publish these on our website to share knowledge and experiences.

EXARC has a number of experienced colleagues who are willing to help other members to look at programming and to help you find solutions. Together, they form a response team on subjects of for example interpretation, marketing, education and management. It is about practicalities, tone of voice in marketing, new house regulations, focussing on new target groups or insurance liabilities, to name just a number of points. Please contact us via info@exarc.net.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dott.ssa Maura Stefani for commenting on several drafts of this article; we also thank Pascale Barnes for her useful comments.

Bibliography

The Economist, 2020. The changes covid-19 is forcing on to business. [online] 11 April. Available at: < https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/04/11/the-changes-covid-19-is-forcing-on-to-business > [Accessed 18 April 2020].

Hansen, T., 1972. Vinterhavn: Nye rejsedagbøger. København: Gyldendal.

Museumvereniging, 2020. Kwart van musea dreigt door coronacrisis om te vallen. [online] (9 April 2020) Available at: < https://www.museumvereniging.nl/kwart-van-musea-dreigt-door-coronacrisis-om-te-vallen > [Accessed: 18 April 2020].

Organisationen Danske Museer, 2020. 9 ud af 10 museer står på spring for at genåbne - men regeringen tøver. [online] (17 April 2020) Available at: < https://www.dkmuseer.dk/nyhed/9-ud-af-10-museer-st%C3%A5r-p%C3%A5-spring-for-at-gen%C3%A5bne-men-regeringen-t%C3%B8ver > [Accessed: 18 April 2020].

Pine, B.J. and Gilmore, J.H., 1999. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theater & Every Business a Stage. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Tilkin, G., 2016. Professional Development in Heritage Interpretation: Manual. [online] Bilzen: Landcommanderij Alden Biesen. Available at: < http://www.interpret-europe.net/fileadmin/Documents/projects/InHerit/Manual-InHerit-EN.pdf > [Accessed: 18 April 2020].