The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

From Gastonia to Gotha: My Thoughts and Impressions on doing Museum Work

What I consider my first real museum work came from a message on my phone on January 9th 2018 from Ann Tippitt, the Director of the Schiele Museum in Gastonia, North Carolina. Gastonia has a sister city in Gotha, Germany and in 2017 the Museum in Gotha sent an exhibit to the Schiele Museum so this year the Schiele Museum planned to send an exhibit to Germany on the North Carolina Piedmont. Ann asked if I was interested in outfitting a Catawba Indian mannequin for the exhibit. She wanted a complete set of clothes, weapons and gear. Inside I was happy, but my mind was saying can you do this? The problem for me was that my good friend and mentor, Steve Watts, who worked for the museum, would have done this work. He died a little over two years ago so the Schiele Museum needed someone to step in and do the project. I studied with Steve for twenty eight years, so Ann asked me to help them with the project. I have replications in museums all over North America, but they are mostly single items and not large orders. Some of my items are on display, while others are used by museum staff for demonstrations. This project was going to be large. I find that three factors are concerned when doing museum work; money, time and understanding.

Money is a factor in any job. Some museums receive grants for projects, but most have to budget for projects. Sometimes there can be a combination of both. When a museum contacts you to do something have a set price in your head. The museum approached you for a reason. Do not make promises you cannot deliver for money. Consider raw materials, your time, travel, your expenses and most importantly why the museum chose you. I met Steve Watts, who not only worked at the museum for over thirty two years, but also taught classes there, twenty eight years ago. I had taken hundreds of classes from him and the Schiele Museum was well aware of my abilities. I was asked to do the mannequin based on my association with Steve Watts. Money can be an issue though. Some museums have large plans, but small budgets. Then you have to make the choice in your head and heart to do the project for the budget they have because the item will be viewed by thousands and could potentially lead to more work. You can also loan expensive items if the exhibit is temporary to alleviate some costs. If you are bidding on a museum job, do not underbid to get the job and lose money on a job.

Time is more of a factor to the replicator. Most museums do not understand the time involved in replicating items. You have to have the raw materials on hand or be able to collect or buy the items. Some raw materials have to season or dry out while others can only be collected during a certain time of the year. In the case of clothing you have to have finished brain-tanned buckskin on hand before you can sew the clothes. Even pottery takes time because you have to make the pot, let it dry and then fire the pot. Time can be more stressful on the person making the replications. To be fair though, the museum people are stressing out too! I had a deadline that kept changing because the items had to be shipped to Germany. Most museum work is for an exhibit at the museum so you do not have to worry about international shipping.

Understanding is the final hurdle. Some museum people do not understand the magnitude of what they are asking. For example, for clothing you have to have brain-tanned buckskin. A hide takes eight to ten hours to finish. On a shirt you have to match the front and back size, weight and colour. The sleeves also have to match the weight and colour of the shirt too. Finally you have to measure correctly, cut the hides and sew up the shirt. I was fortunate because Ann Tippitt and her husband, Alan May, were not only archaeologists, but had taken primitive technology classes and they both understood what they were asking.

The Mannequin Replications

The initial meeting went great. Ann had a list of what she wanted and I had a deadline and a plan. Tony Passeur from the Schiele Museum was also involved because he was going to Germany to set up the mannequin. I met the mannequin that day and it was a real punch in the gut. The mannequin was an old model which Steve had dressed as an Ice Age Hunter over twenty years ago. The hair on hides were old and dry rotted and were stapled to the mannequin to fit. As we took off the skins I immediately saw some challenges. The mannequin only had flesh on his arm from the elbow down so the shirt was going to have to be long sleeved. Luckily the head, arms and torso were all removable so it was going to be easy to dress. I was commissioned to do a shirt, leggings, moccasins, bow, arrows, quiver, blowgun, blowgun darts, blowgun quiver, necklace, pouch, belt and headdress. I suggested a rabbit stick (non returning boomerang) because it was such a documented Catawba cultural item.

Now I know people who do this type of work and they contract or buy all of the replications from individuals, mark up what they paid for the items and make a profit that way. I wanted to make all the items so I could say the whole mannequin was made by me. The only item I had never replicated before was the headdress. This challenge made me think of Steve though. He always put a workshop on his schedule that he had never done before to force himself to learn a new skill. I was going to make the headdress last.

I did get help from three different people. Greg High is a friend who replicates Native American pottery. I contacted him because I needed to make clay beads for a necklace. James Parker is a renowned flintknapper and bowyer who let me use his shop to build the bow. Finally, Matt Weatherholtz provided some hides because of time restraints and weather there was no way I could finish all the hides and sew the clothes.

I should mention a word about replicas. A true replica is something made using, as far as we know, the same tools and techniques used in the past. A reproduction is an item that looks like the finished item, but is not done using the same tools and techniques of the past. Flint knapping is one of those skills where you see lots of reproductions and not a lot of replicas. Modern flintknappers strive to make the best. The archaeological and museum communities help create this issue. When an archaeological book is published the books are typically filled with photos and drawings of the best examples found due to space issues. The same issue occurs in museums for the same reasons. There are a lot more mediocre and bad examples of flint knapped pieces then the beautiful pieces displayed or illustrated. Many primitive points and knives have stacks, curves, thick areas, humps and hinges. These issues did not matter to a prehistoric person who was concerned with functionality and obtaining his or her next meal. I replicated six triangle points and a knife blade for the mannequin. I used rhyolite which would have been used by a prehistoric Catawba. I did not use the better grade rhyolite, but the grainy grade most artifacts are found made out of. I purposely left a stack on the knife blade to make a true replica. I could have gotten this high spot off, but it did not affect the function of the knife so I left it. All of these were knapped with white- tailed deer antler billets, local hammer stones and antler tine pressure flakers so they were true replicas.

I had to do approximately fifteen hours of research and reading for this project. This was necessary to make sure that everything fit with a pre-contact Catawba warrior. I was lucky because I had Steve Watts’s library and all of the books on the Catawba Nation in my possession. I measured the mannequin several times and did initial sketches to make sure everything was going to work out and look nice. As a nod to Steve I wanted to include as many black bear items as possible. The bear was his totem and his first company of museum replications was called Old Bearskin Productions.

I worked on pottery with Greg High first. I knew we had a short window because the clay had to dry and we needed a day to fire outside without rain or high winds. I hand rolled all of the beads for the necklace and also made three pieces of pottery to fire. I spent two days on the pottery and beads and a day outside firing. The weather held out and we fired the pottery outside on a beautiful winter day.

The next project I worked on was a bow quiver made of bear fur. I used an old bear skin rug and cut a piece of rawhide as a liner for the quiver. I accented the quiver with brain-tanned buckskin and made a brain-tanned strap too. The quiver took about twelve hours to complete.

For the arrows I used river cane (Arundinaria gigantea), a native bamboo species. I used the documented Cherokee two feather fletching method (Swanton, 1946). Turkey feathers were used to fletch the arrows. The rhyolite triangle points were attached to black locust fore shafts with hide glue and sinew. I decorated the fore shafts with burnt spirals. I could have skipped the points and fore shafts and just used fletched pieces of cane since they were going to be in a quiver. This can be a cost saving method if you are doing museum work. If your item is going to end up in a case or a quiver you only have to make the part that shows look great.

The moccasins were Southeastern Pucker-toe made out of brain-tanned buckskin. The mannequin had no toes so I could be pretty flexible about the size. I used my own foot for the pattern. I used the well-researched article “Basic Footwear of the Southeastern Indians” (Wood, 2000). I had to pad the toes to make the moccasins look like a normal foot. The mannequin was also on the display with a post attached to the foot so I had to cut a hole in the moccasins to fit around the post.

The leggings were Cherokee centre seam with no fringe. Made of brain-tanned buckskin, they had thongs on the side to attach to a belt. They went up to about mid-thigh (Swanton, 1946). I made leg ties out of the left over bear fur to be tied around the leg below the knee to help hold up the leggings. After contact, most of the leg ties were finger woven.

The brain-tanned buckskin shirt was by far the most time consuming piece of the project. The shirt had to be long sleeved because the mannequin had wooden upper arms. Because of this, I needed a minimum of four hides on the shirt; one for the front, one for the back and one each for the sleeves. I measured for the shirt a minimum of three times to make sure none of my measurements were wrong before I cut any of the hides. I spent over twelve hours hand sewing the shirt. I decided to lace the sleeves to the shirt at the shoulder in case I had problems with the way the arms bent. This way I could take off the sleeves and lace them at the shoulder. I also decide to use thongs on the side of the shirts so I could get a better fit.

Obviously, there are no sources for pre-contact Catawba shirts. I consulted Theresa Kamper, the foremost authority on brain-tan buckskin and clothing, and every piece of available literature to decide if I wanted fringe or no fringe on the shirt. I could not find a definitive answer, so I decided to go with no fringe.

I wanted to make the shirt long so I could save time, money and material by not making a breech clout. When doing museum work and replicas, take the time to talk to the people involved so you can come to terms on items that would be expensive and not seen.

The necklace was made of six black bear canines and clay beads strung on a buckskin thong. Bear teeth are hollow at the root, so you have to be careful when drilling them. Many teeth crack when they are drilled but this gives them a more authentic look to teeth recovered archaeologically. Obviously, the necklace was a nod to my deceased mentor, Steve Watts.

A simple buckskin thong was tied around the mannequin’s wrist. This was so you can have a piece of cord available to tie something whenever you need it. The cord was about eighteen inches in length.

The blowgun, darts and quiver were easier for me because I was comfortable with the technology because I have made thousands of blowguns. I decorated the blowgun with a spiral burn pattern which had been documented among the Creeks. I made all of the dart shafts out of cane because it would have been very time consuming to split hard wood for shafts with stone tools. Native Americans would have split green wood, but I would have had to force dry the shafts and didn’t want them crooked. Some of the cane pieces were flat which I heated and twisted to give them spine. The other cane pieces were small diameter round pieces. The darts were fletched with thistle and I used dogbane fibres to secure the thistle to the cane shafts. The quiver was made of a gourd.

All the bow information was collected by Steve Watts and compiled in The Encyclopedia of Native American Bows, Arrows and Quivers (Allely and Hamm, 1999). There were two Catawba bows to choose from, a flat bow and crowned belly or “D” bow. I made both of the bows and let them chose the one that they wanted. Both the bows were made of black locust like the originals. When replicating bows, ask the museum staff what they actually need. If the bow is going on a mannequin or in a case, it doesn’t matter if it has a twenty pound draw weight. If the bow is going to be used in programs and demonstrated with, ask what draw weight they want. Both of the bows had a forty-five pound draw weight. I used the shop and expertise of James Parker of Huntworthy Productions to supervise the bow making.

For small items, I made a buckskin pouch with bear claws for toggles on the drawstrings. I also made a buckskin sheath for the rhyolite knife. The sheath had a rawhide liner to protect the blade. I also made a buckskin belt to hold up the leggings and attach the knife, pouch and blowgun quiver to. I also stuck a Catawba style rabbit stick in the belt. This was actually a rabbit stick I made out of hickory in one of Steve’s workshops. It was well used and really set off the mannequin.

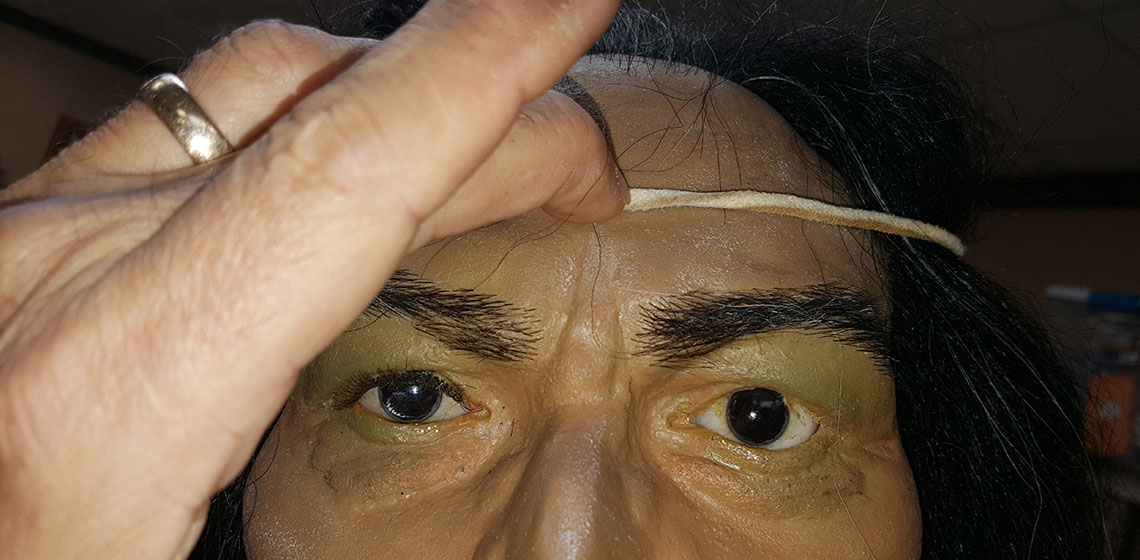

The final replica I did for the mannequin was the headdress. The Catawba have a distinct documented headdress made of turkey feathers in a round band around the head. I went to the Catawba Museum on the reservation in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The headdress there scared me. They had fur wrapped around the band. They were helpful there, but did not know what they had. They said the fur was rabbit or mink. It was a long continuous piece of fur so more likely was otter or beaver, which would have made sense for people living along the river.

In the end, I just folded a piece of buckskin around a piece of rawhide for stiffener and stuck the feathers between the rawhide and brain-tanned buckskin. I put a row of large turkey feathers around the headdress and filled in the gaps with smaller feathers. I laced the back so I could get a better fit. It looked really good on the mannequin, but off the mannequin, I was not impressed with it.

The Reveal and Trip to Gotha, Germany

After I finished everything for the mannequin I brought it all to the Schiele Museum for the final dressing. We were going to dress as much of the mannequin as we could and then a company was going to put him in a crate called a coffin and ship him to Germany. We did a full dressing so we could see the whole effect, but the blowgun, bow and other items were going to be packed in the crate and put on the mannequin in Germany. My wife, Jana, watched the final dressing and photographed the process. Everyone at the museum was so impressed with the work and I heard gasps when I put the headdress on the mannequin.

I did have a stroke of luck with the mannequin. I had already planned a trip to the Netherlands and was going to be in Europe during the exhibit opening. Ann asked me if I could come to the exhibit opening and demonstrate skills. I would also get to do the final dressing of the mannequin and make it fit my vision. I asked my Dutch friend, Liza van Rijn, if she wanted to go to Germany to see the exhibit and my mannequin. Liza was with me the whole process; listening to my doubts and fears, hearing my triumphs and encouraging me through the process. Of course she said yes.

We road tripped to Germany and arrived in time for the final dressing of the mannequin. Liza helped me put on the quiver, headdress and the final details. The Kunst Forum in Gotha did an amazing job displaying the exhibit. The mannequin was on the second floor and when you came up the stairs my mannequin stood like a silent sentinel overseeing the exhibit. Everyone was instantly drawn to the mannequin. I was happy with the reception it received. During the opening of the exhibit I demonstrated flintknapping and blowguns. Liza talked about items on my display table as I knapped. We were treated like special guests and got to attend fancy dinners and receptions. The German museum Directors Beate Aé-Karguth and Andreas Karguth were gracious hosts. They set up a host home for us to stay at with Helga Wilforth who treated us like family. We even got an award from the German Museum for demonstrating.

The museum mannequin was a success. It made the German Newspaper three times. I pulled off the headdress, something I had never done before, and it really changed the mannequins look. I know Steve would have been proud of me. Was it all worth it to me? I guess so because I just got commissioned to help with two more mannequins for the Schiele Museum which will be on display in March.

Keywords

Country

- USA

Bibliography

Allely, S. and Hamm, J., 1999. Encyclopedia of Native American Bows, Arrows and Quivers. New York, NY: Lyons Press.

Merrell, James H., 1989. The Catawbas. New York, NY: Chelsea House.

Milling, Chapman J., 1969. Red Carolinians. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Speck, Frank G., 1938. The Cane Blowgun in Catawba and Southeastern Ethnology. American Anthropologist, April – June, pp.198-204.

Swanton, J.R., 1946. The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Reprint 1979. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Wood, G., 2000. Basic Footwear of the Southeastern Tribes. Bulletin of Primitive Technology, 19, pp.46-56.