The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

Digital Saryazd: Increasing Tourist Engagement Using Digital Documentation

Saryazd Castle is located in Yazd Province, Iran. The castle dates to the Samani era, with later expansion during the Safavid era. Constructed entirely of mud-brick, Saryazd was continuously used until the mid-20th century as a vault, protecting both people and their property. Earthenware structures require continual renewal in order to maintain the integrity of the structure. Today, visitors can witness traditional construction techniques, albeit with some newer materials. The site has a magical quality which is enhanced by the current caretaker, Mr Hosein. The lighting of the fire, serving of tea, and his warm hospitality breathe life into the castle and make this a special visit for guests. The castle has developed into an open-air museum and is unique within the region. Considerable restoration work has occurred in recent years, with the desire to increase the number of visitors. Recent weather patterns and excessive rain have created challenges in maintaining the integrity of the castle's fabric. A project to digitally document Saryazd Castle was undertaken in December 2019 and aimed to document the castle as it currently stands. The techniques used were close-range photogrammetry, high-resolution photography and the creation of a virtual 360º tour. The documentation can be used in the future for preservation, conservation and popularisation of the monument. This paper aims to raise a discussion among professionals about living museums and to suggest guidelines for enhancing their potential as open-air museums.

Introduction

In December 2019 our team travelled to central Iran to document Saryazd Castle. We intended to use popular digital techniques to document the castle with an aim to create a platform for generating higher tourist engagement and presence on-site. The project aimed to stimulate economic growth and make the castle a self-sustainable open-air museum. Saryazd citadel is a fascinating site, where the physical fabric is woven with narratives of the past. Several strategies have been devised as a result in order to maximise the museum's potential. The aim of our discussion is not only to present these ideas but also to open a general discussion on guidelines for enhancing the potential of open-air museums.

Saryazd Castle

Location and History

The village of Saryazd is located in central Iran, approximately 50km from the historical city of Yazd. At one time, this was the largest village in Yazd Province owing to a constant water supply and fertile farming land (ICTHO 1974). Today the village has a small residential population, with an influx of weekend visitors. Among the tourist attractions available to visitors is Saryazd Castle. This castle was not known as the seat of a ruler; it was built as a citadel where the local population could go during times of distress (Naiemi 2018, p. 225). The date of construction is generally accepted as occurring during the Sassanid era, 3rd to 7th centuries AD. However, the village of Saryazd is said to have formed in the 8th century (ICTHO 1974). The earliest evidence of the castle dates to the Al Mozafar dynasty in the 14th century, with expansion during the Safavid dynasty in the 15th to 16th centuries (Moghadam 2006). Based on the architectural typology a date during the Samani era, 9th to 10th century, has also been suggested (Bafghi et al. 2016, p. 19).

Architecture, typology and functionality

Saryazd Castle is a citadel surrounded by a moat and entry via a single bridge (See Figure 1). The fortress consists of an inner and outer fortification wall, storage rooms, and multiple defensive towers. There are three floors of occupation, with estimates of some 1500 rooms (Babaei, 2007). Much of the top levels have disappeared, and this number is probably closer to 850 based on the remaining evidence. The rooms were mainly used to store valuable items, such as grain. These food items were stored in "Tapos", large earthenware vessels which could hold up to 300kg (Moghadam, 2006).

Earthen architecture is a dominant construction technique for much of Iran's built heritage. Residential compounds, caravanserais, and mixed complexes like Saryazd, served to protect communities against natural forces, human incursion or animal threats. Defensive castles are spread throughout different provinces within Iran and share not only similar functionality, but also form and style. These structures are of great importance to Iran's heritage, but unfortunately, they are rarely studied by scholars (Naiemi, 2018, p. 203). In addition to being defensive structures, these compounds were an integral component of social cohesion (Naiemi, 2018, p. 205).

The inner section consists of housing elements and storage rooms, which were spread alongside a central road with inner narrow paths and corridors. Naiemi suggests that the complex was arranged according to a well-drafted predetermined plan (2018, p. 220). The rooms are very tight, with shelves and niches. Only those located on the second and third level have natural light entering during the daylight. This is a clue that long term residency was almost unlikely (Naiemi, 2018, p. 225). Rooms are also located between the inner and outer fortification walls, and these were likely added at a later stage as the population within the walls grew (Hajisaeid, 2020).

Water management is paramount in desert environments. Water to the village came from the Madvar source, located in the mountains to the south west of Mehriz (ICTHO 1974). In addition to this source, Saryazd citadel had a water cistern (See Figure 2). Water was held in the surrounding moat and channelled through earthen tubes. Rainwater could also be collected in the cistern during times of siege (Naiemi, 2018, p. 223). The use of qanats is common in Iran. These are a series of tunnels dug by hand which carry water from underground sources into cities.

Architectural survey

There are many known causes of damage to earthenware structures, including coving, cracking, wind erosion, infiltration of flora and fauna, human activity and natural disasters. A documentation project was suggested in conjunction with the Iranian Federation of Tourist Guides Associations (IFTGA) to record the structure, providing documentation for research, monitoring, education and preservation. This was accomplished through the creation of a 360º virtual tour, photogrammetry and high-resolution panoramic photography.

While working on the digital documentation of Saryazd, it became apparent that the monument suffers from many structural pathologies. The team created a short report of their origin and the dangers they represent for the entire stability of the complex and the architectural elements themselves. This report, together with the 360º documentation, could be used as an archive for future restoration-conservation activities.

Pathologies

The structural pathologies are deformations which can result from either a singular or a combination of destructive processes, acting in a particular sequence. Exposure and weathering can present challenges in stabilising earthen architecture (Correia et al., 2006, p. 4). Within adobe masses, the expansive action of the moisture and the wet-dry cycles, salt crystallisation, vegetation, cracks, or human-made damage are among the most common destructive factors. Wind erosion is also a concern, while on the site, the wind was often excessive, which causes damage to the outer layer over time if it is not maintained. Saryazd fell into a state of disrepair after it was no longer densely populated, after the 18th century. Maintenance is the best approach to ensuring the durability of earthen architecture. (Baca et al., 2007, p. 62).

Moisture

Saryazd is located within a desert environment. Excessive rains and flooding can accelerate damage, as happened two weeks prior to the team arriving. Similar flooding occurred in the 1950s which destroyed agricultural land, parts of the village, as well as areas in the citadel (Babaei, 2007). Earthen architecture is particularly sensitive to changes in the environment, and appropriate conservation, restoration and management of the site is required (Colette, 2007, p. 55).

Moisture is not the enemy of mud-brick, and it can withstand a certain amount of water exposure. However, when exposed to excessive moisture can result in a loss of compressive strength, leading to material failure (Crosby, 1987, p. 35). Moisture enables salt to enter the fabric. When heated, both salt and water can expand (Crosby, 1987, p. 36). Mud-brick has a low thermal conduction, that controls the process of heat transfer (Keshtkaran, 2011, p. 431). It is the wet-dry cycles where excessive heat is combined with the expansion of salt crystals and water where failure occurs (Crosby, 1987, p. 38). Cracking within the fabric walls shows evidence of these processes (See Figure 3).

Water drainage is an issue at the site. Drains have been placed at numerous locations across the site (See Figure 4). Unfortunately, these often drain into other areas in the site, resulting in coving at the base of the walls. In addition, deep gullies run vertically through the walls (See Figure 5). There are limited financial resources for conservation, so documentation can be used to prioritise the most damaged areas for repairs. Finally, coving is present underneath the foundations of the walls. This coving was present in February 2019 (See Figure 6), and this was more prevalent in December 2019 (See Figure 7).

Restoration

The structure has been largely uninhabited since the 18th century and consequently has not been maintained. The conservation and preservation of earthen archaeological sites presents a complex problem, mainly because of the fragile character of the materials and the exposure and weathering, as well as the difficulties and limitations in stabilising such structures (Correia et al., 2006, p. 4). The worsening condition of the structure until recently was due to a lack of care. Maintenance is by far the best tool to guarantee the durability of earthen architecture and the only way to conserve adobe structures is to restore the original constructive systems as a whole (Baca et al., 2007, p. 62). Ongoing restoration raises the question of authenticity. In cases like Saryazd, where renewal is a constant process, it is hard to draw the line between old and new. In areas where entire constructive elements are lacking, specific restoration techniques should be performed, and particular rules must be followed to guarantee a holistic and transparent approach. From what we observed during our fieldwork, the restoration in Saryazd follows traditional techniques but uses modern materials. These are easily distinguishable from the original structures, thereby corresponding to recognised conservation guidelines.

Digital Saryazd

The "Digital Saryazd" project was undertaken in conjunction with the ITFGA. The goals of the project were to document the fortress as it stands and to create a virtual tour which could be hosted online. This tour would also serve as an online museum, giving access to the site by enabling virtual visitors who could not travel to Iran. The hope was that this could also generate interest for tourists wanting to tour the site physically. Close-range photogrammetric models were created that can be used for graphic reconstructions. 360º photography can be used to document cultural heritage. It has been used for both scientific purposes, and to promote tourism. In terms of tourism, an internet presence is key to ensure that the heritage site is known when planning an itinerary (Solima and Izzo, 2018, p. 116). Panoramic tours are becoming commonplace for museums and heritage sites to host on their websites. The high-resolution images are a valuable resource for students and scholars who can now virtually discover some of the most famous sites on earth (Koehl et al., 2013, p. 386). Iran is inaccessible as a tourist destination for many due to the current political climate. Further, when natural disasters occur, or periods of a pandemic, virtual tours can give access to the world's heritage through the internet. Iran is located in one of the most earthquake-prone areas in the world. Documentation of this type can assist in a complete reconstruction as happened after the Bam earthquake in 2003 (Misra 2008, p. 615).

In December 2019, our team started the first stage of the documentation project. This stage required a detailed survey of Saryazd, visiting all accessible storage rooms and corridors. Two local guides from Yazd assisted in familiarising the team with the architectural typology, the fundamental historical and artistic values, as well as the modern culture of Iran. Over a period of ten days, 30,428 photos were taken. The results were over 70 panoramic images which were used to create the virtual tour. Areas which were dangerous or inaccessible were not photographed and will be attempted in the second stage of the project. The software allows more panoramas to be added to the tour at any time. As rooms are renovated, they can be added to the tour, and older panoramas can be archived for future reference. A virtual museum can be created, and the eventual aim is to document the 800 or so rooms. These would not all be included in the virtual online tour due to the amount of time to load, leading to end-user confusion over the volume of rooms. However, the tour can be saved with all 800 rooms and reserved as a record of the citadel at that moment in time.

Stories and Experience

There is scant written history of Saryazd Castle, in either Farsi or English, that made discovering more of the local history challenging. What does exist are ethnographic stories passed on through the local villagers. One such story is that of the last inhabitant, Fateme. Despite being offered a house in the village, Fateme chose to live in the castle as a caretaker until her death forty years ago. After her death, the castle fell into a state of disrepair and was inaccessible for visiting. In 2012 a local benefactor stepped in to finance the citadel's restoration (UNIC 2014). Mr. Saryazdi had grown up in the village and has provided funding to help restore and reinvigorate the village. The care and protection of a childhood home might seem like a romantic story, but in general, there is an inherent respect felt toward the local heritage in Iran.

Notably, much of the world's history is located in Iran; however, funding can be a challenge. With sanctions currently being in place, there are few opportunities for economic growth. As a result, the best way to protect their heritage is by repurposing. Many sites are being turned into restaurants or caravanserais, such as Zein-O-Din, in order to raise the capital to maintain the built heritage. Saryazd citadel is currently operating as a heritage site, with a desire to turn the visit into an experience. There are many castles in Central Iran, though, by our own perception and the conversations we have had with other professionals and visitors, none has the magical quality of Saryazd. Part of this magic is the hospitality of the site's caretaker, Mr. Hosein. Every morning he makes tea and relays stories to tourists about the castle, that are translated through tourist guides.

The workers who restore the castle provide a sense of atmosphere. With the exception of using purchased bricks, the restoration of the castle is done using traditional techniques. The workers breathe life into the castle, adding sounds, sights and ambience, which all add to the sense of truthfulness. The neighbouring village provides an added experience for visitors who want to extend the feeling of atmosphere. When Mr. Hosein makes the tea, it has the scent of the fire, and the warmth of the cup initiates the telling of stories. Everyone has their own stories about Saryazd, and about Iran.

Breathing new life into Saryazd Castle and the surrounding village is seen as a way to entice people to visit beyond the usual weekend visitors during the high season. Tourism requires support infrastructure, including hospitality and transport. This adds value to the economy through secondary business opportunities (Solima and Izzo, 2018, p. 116). The aim is to improve the economic position of the village's inhabitants. The castle is currently seen as an open-air museum. There are more opportunities which could be taken advantage of to provide a more complete experience for tourists. This concern is where the advice of the experienced EXARC community can be of assistance. The authors wholly welcome feedback and advice on these ideas.

Cultural tourism is recognised as a specific market segment. Domestic tourists are motivated to travel for intangible heritage events, such as special national or religious ceremonies (Hajisaeid, 2020). Currently, over 40% of international tourists identify cultural heritage as a key motivation for travel (Koskowski, 2019, p. 151). Many of these tourists are looking to consume experience over tangible elements (Wilson and McIntosh, 2010, p. 141). This holds true for both domestic and international tourists who are looking to participate in new activities. They want to engage their senses with an experience they cannot have at home (Hajisaeid, 2020). Expectations for destinations include learning about the local culture in terms of customs, food, landscape and social values. Culinary tours are becoming popular. Tourists come to eat new foods but also learn how to cook them, and experience harvesting the ingredients, such as Saffron, that could not be experienced elsewhere in the world (Hajisaeid, 2020). There is a desire to connect with local residents with a view to gain an 'authentic experience' (Simeon and Martone, 2014, p. 150). The objective is to generate creative ideas to complement the existing infrastructure and invite tourists to experience the magic of Saryazd castle.

While this paper aims to create a forum for suggestions on how to proceed in broadening Saryazd citadel's offering as an open-air museum, it would be remiss not to briefly mention potential damage which could be caused to the site from the increase in tourist numbers. In order to mitigate this damage, a site management plan should be the first stage addressed. The site management plan can help us to understand potential threats to the site, to understand how these threats can be reduced and how to recover the site in the event that they do happen. For an extended discussion on site management plans and their benefits refer to Pederson (2002). Potential challenges to identify are:

- Social or cultural change

- The conflict between local residents and tourists as a result of increased visitor numbers

- Accidental damage, erosion and the wear and tear as a result of the increased numbers

- Vandalism or deliberate damage

- A safety assessment and outlining safe routes of travel through the site

(After Timothy, 2011, Chapter 7).

Museum environments present the user with multiple stimuli, so digital content has to be carefully curated to consider the spatial and physical environment (Solima and Izzo, 2018, p. 118). On the surface, mud-brick complexes can appear to be a singular shade of brown. However, Saryazd is made up of many layers, textures and colours. The correct use of digital media could enhance the user experience at the site by presenting local anecdotes and stories at specific spots which highlight these sections. This can be achieved through the use of QR codes. QR codes are barcodes that can be scanned using an application on an internet-connected smartphone. QR codes can be scanned, and audio or video can be played through the visitors' personal device. This solution requires a much smaller investment than the site needing to purchase and maintain their own devices (Solima and Izzo,, 2018, p. 119). It also negates the need to place signboards up, which ruin the overall view. As QR codes provide a link to external material, they are easily changed over time. Alternatively, temporary exhibits using these codes could be implemented for special events or festivals. The use of an individual's mobile device means that the site will not need to supply the internet, the installation of which would damage the fabric. While using QR codes can facilitate the implementation of multi-language options, currently, in Iran, tourists are unable to purchase SIM cards so there will be limited access to the technology for foreign visitors. Many visits are conducted in conjunction with a local guide, so in the short-term this is not seen as a hurdle.

Combining longer-term planning with business initiatives can benefit the local economy by capitalising on the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage (Simeon and Martone 2014, p. 150). The importance of handicrafts as intangible heritage is already well established in Iran. In Isfahan 9,000 craft and folk art workshops exist, across 167 different disciplines (UNESCO 2017). The layout between the inner and outer fortification walls lends itself to hosting market stalls, in the same vein as a bazaar. These stalls could be temporarily placed during peak seasons in order to generate interest in local handicrafts. This is complementary to existing strategies within Iran, as well as providing an activity for visitors. This market bazaar would add to the sense of life within the castle. There is an existing infrastructure in terms of water and electricity supplied, however further bathroom facilities would need to be supplied. There was also some discussion as to the viability of providing these stalls year-round, and this would be challenging in the low season when there are fewer visitors. The concern is that rent could not be charged to stallholders if foot traffic is not maintained, otherwise this is not an economically viable solution. Currently, we do not have an answer for this, and it requires more thought and discussion with stakeholders.

Guides who bring tourists to Saryazd are a combination of driver-guides who accompany groups for the entire period of their stay in Iran. There are also local guides, based in Yazd, who provide shorter tours, such as day trips. Training provided to guides before they are registered ensures continuity in the way that information is conveyed. An alternative option is to have a guide who is dedicated to presenting Saryazd Castle and village. This guide could be used in conjunction with existing guides, or they could provide the service for visitors who arrive without a guide. This method of using specialised guides for specific sites is already an established tradition within Iran and does not need to compete with the services already being offered. The current barrier for this is again, seasonality.

The magic of Saryazd Castle lies in its narrative. For many tourists, photography is a way to tell their travel stories; they reenact their experiences by using images as performance (Urry and Larsen, 2011, p. 172; Koskowski, 2019, p. 152). Images taken at iconic sites creates a sense of self and permits a sense of authenticity. The selfie has taken over this form of storytelling (Koskowski, 2019, p. 153). In order to move people away from merely looking for the iconic shot of a site, there is an opportunity to use this form of expression to get visitors to move around heritage sites (Koskowski, 2019, p. 155). The hashtag #saryazd (also including #saryazd_castle and #saryazdcastle) has three iconic areas that are posted on Instagram. These areas are the staircases after the second entrance (See Figure 8), the Gate of Farafar (See Figure 9) and a birds-eye view (See Figure 10). The Gate of Farafar is in the village itself, and this frames a modern sculpture, that has become an iconic symbol. Taking selfies at sites can also be dangerous, with numerous stories in the press about people who have fallen and died trying to get that Instagram shot. Frames could be placed around the site, in safe places, where photos could be taken and encouragement given to add hashtags and post to social media in order to promote the site. Placing these frames in strategic locations also ensures that visitors move safely through the site, and could be placed in such a way as to direct the flow of traffic. These frames also ensure that more than three areas are recognised in images and talked about when people return home.

A suggestion was made to create a light festival. However, upon speaking with Mohsen Hajisaeid from the ITFGA, having an event at night time may not be an ideal solution due to the location. Hajisaied thinks that we need more creative solutions for Saryazd Castle as it is a unique and special place. He would like to see a treasure hunt inside the castle. Groups could have clues given to them, with objects planted within the castle. The winner would take home an award, and this award would bring warm memories to them. Other creative ideas to engage visitors at the site are required in order to expand the current offering.

Tourist accommodation is a significant resource in heritage tourism. Heritage accommodation establishments are uniquely placed because they provide cultural, historical, culinary and sometimes adventurous experiences simultaneously. Heritage accommodation holds great potential. There are a variety of uses which provide long term stability for tourism, including presenting local identity, history, and offering first-hand experience in a modern environment (Lee and Chhabra, 2015, p. 103). When staying in a heritage area, travellers can visit or stay in a property where people still live traditionally, while also being provided with the luxuries of modern life, such as Wi-Fi.

As mentioned in an article by Mendiratta (2013), hotels and other accommodation structures must be "guardians of the past, hosts of the present ". These properties must act as a vehicle for sustaining the local history and local communities. Visitors should be encouraged to spend money in areas where they wish to enjoy the historic environment. This concept aligns with the current understanding that Iran's heritage can only be saved by repurposing for commercial enterprise.

While travelling around Yazd, our team was able to enjoy cultural experiences as tourists visiting Iran. This exposed the team to the unique events being developed to cater to the needs of contemporary cultural consumption. We visited traditional restaurants; we cooked with a local family; we visited various sweet shops and traditional markets selling spices, and a factory processing sesame products. We also visited several converted caravanserais. One is now a hotel offering various levels of accommodation. The other is a restaurant and market selling traditional handicrafts. There is a wide range of offerings for accommodation in Iran. There is a perception that western tourists prefer hotel accommodation and few Bed and Breakfast options are offered, although available.

We believe that the village of Saryazd has the capacity to provide a variety of attractions and accommodations for its visitors. Currently, there are plans for building accommodations outside of the citadel, and one restaurant is already under construction. In the future, visitors could choose between boutique relaxation and active tourism. Active tourism creates opportunities for Saryazd's visitors to feel and experience real contact with local people in their environment, while still accessing the historical ambience. Local people act differently in popular tourist sites, and there is a behavioural mask that is always present. Being away from the noise of the big city, tourists can focus on enjoying nature, learn about the culture and Iranian's rural way of life. Attractions could be designed where guests spend their nights at people's houses or local guest houses or even nomads' tents where they are able to interact with the people and get to taste their way of life, cooking and surrounded by their families. The following are the presented ideas, discussed with ITFGA:

- Creating Bed and Breakfast accommodation in local houses:

- This allows visitors to dive into Iranian's modern culture while enjoying local traditions and cuisine.

- Hosting international tourists will increase local income.

- Having to meet certain expectations surrounding the accommodation business, the general living conditions will improve.

- Locals will have the opportunity to learn foreign languages and exchange knowledge about different cultures and history.

- Boutique hotels and restaurants

- sustainable tourism requires accommodations for every taste.

- A comfortable stay will allow long term reservations, which will lead to a higher spend-ratio in the local economy.

- Desert Safaris, nomad tents, themed routes

- Active tourism connects local culture and environment and is a low-impact, socially sustainable way of travelling.

- It engages the local community, providing them with jobs while offering a different perspective on Iranian's nature.

Virtual Museum

Until the long-term goals are accomplished, the IFTGA is looking for ways to increase tourist flow to Saryazd. Merging reality into a virtual world opens many possibilities for researchers, scholars and future tourists. The use of internet engagement has been shown to increase site visits by as much as 48% (Solima and Izzo, 2018, p. 117). A virtual environment allows visitors to access the site from abroad and to experience user-friendly narratives. Moreover, such data is a digital archive, that preserves the knowledge and conditions of the site at a certain point in time, such as in a museum setting, enabling remote viewing of those spaces that are difficult or impractical to access physically or do not exist anymore.

As mentioned above, the charm of Saryazd is in the stories told and the hospitality shared. The objective for the second stage of Digital Saryazd is to tell the intergenerational stories of the locals to the public, creating a narrative for online visitors. The project is at its very beginning, so it is too early to present a structured plan, but a general layout looks like this:

- Designing the narrative of a guided tour

- Introducing information in the form of texts and information buttons

- Integrating videos and links to the photogrammetric 3D models

- Voice over as a form of storytelling, using known local legends and characters

- Symbols (avatar, points of view, information)

- Calculations of the expected virtual visits

(after Koehl et al., 2013, pp. 387-389).

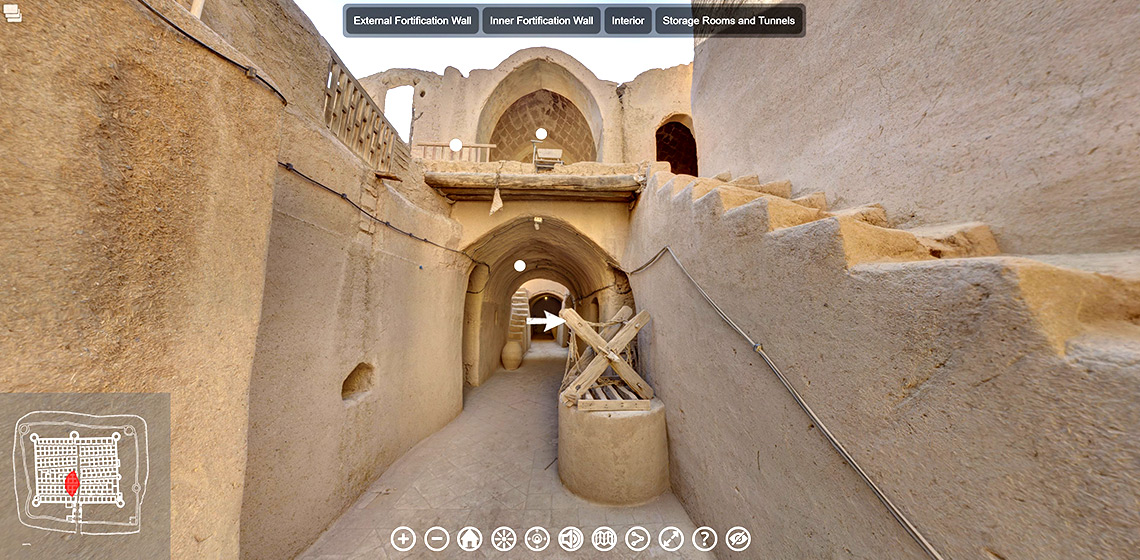

The virtual guided (See Figure 11) tour will allow a visitor who has never been in Saryazd to walk there virtually on a PC, mobile device or with virtual reality goggles. The scenario will follow a general route, revealing the essential aspects of the ground plan, architecture and fortification. A map will facilitate the route by showing the position of the visitor at any given moment.

The Digital Saryazd project aims to reveal the importance of this heritage by creating a virtual musem. Approximately 60 of the 360º panoramas from the virtual tour are already live on the internet. All data has been provided to ITFGA, and a dedicated web page will be built to host the data. Further down the track, this tour could be integrated with those from other sites, enabling visitors to take a virtual route through the Silk Road. This benefits not only Saryazd but the surrounding villages.

Conclusion

During our journey in Iran, we had numerous chances to discuss different development strategies and ongoing projects for Saryazd Castle and its surroundings. We had the chance to be working with two very passionate IFTGA representatives and also join the EXARC community. There is more work to be done, including a graphic reconstruction of a section of the western inner gate, a guided virtual tour, a thorough architectural survey and an analysis of similar architectural compounds.

Saryazd is like a gem, hiding in plain sight amongst the desert. Part of the immense cultural heritage of Iran, it is unique in its architecture and history, chiefly in its ambience. While working there for almost two weeks, we discovered new unexplored areas every day. Our job was to document it, but our hearts quickly joined the IFTGA mission to protect it. We wrote this paper because we want to show Saryazd to the world and to collect knowledge and ideas for its future promotion and preservation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Pegah Latifi and Mohsen Hajisaied for their warmth, friendship and hospitality, sharing with us your vast knowledge and passion for your country, which opened up a new world for us during our time in Iran.

Keywords

Country

- Iran

Bibliography

Babaei, N., 2007. Registration document of Old Robat (Caravanserai). Translated from Farsi by Pegah Latifi. Tehran: Documentation Center and Library of ICTHO.

Baca, L. F. G. and López, F. J. S., 2007. Criteria for integration of new structures in the conservation and restoration of adobe ruins: The temple of the ex-mission of Cocóspera in Sonora, México. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment. 95, pp.61–71.

Bafghi, B. T., Zad, H. N. and Khalilabab, H. K., 2016. Typology of the historical castles of Central Iran. Mediterranean Archaeology & Archaeometry 16 (1), pp.9–21.

Colette, A., 2007. Chan Chan Archaeological Zone (Peru). In: A. Colette, ed. Case studies on climate change and world heritage. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, pp.54–57.

Correia, M. and Fernandes, M., 2006. The conservation of earth architecture: The contribution of Brandi's theory. In: National Laboratory of Civil Engineering, eds. Proceedings: International Seminar Theory and Practice in Conservation, a Tribute to Cesare Brandi. Lisbon. pp.233–241.

Crosby, A., 1987. The causes and effects of decay on adobe structures. In: A. Alva and H. Houben, eds. 5th International meeting of experts on the conservation of earthen architecture, Reunion Internationale D'Experts sur la Conservation de L'Architecture de Terre. Rome. pp.33–41.

Cultural and Art Ministry of Iran Kingdom (ICTHO), 1974. Registration necessity of Saryazd castle. Translated from Farsi by Pegah Latifi. Tehran: Documentation Center and Library of ICTHO.

Hajisaeid, M., 2020. Creative ideas for tourism. [Voice message to Seaton, K. and Raykovska, M.] Personal communication, March 17, 2020.

Keshtkaran, P., 2011. Harmonization between climate and architecture in vernacular heritage: A case study in Yazd, Iran. Procedia Engineering 21. pp.428–438.

Koehl, M., Schneider, A., Fritsch, E., Fritsch, F., Rachedi, A. and Guillemin, S., 2013. Documentation of historical building via virtual tour: The complex building of baths in Strasbourg. ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XL-5/W2, pp.385–390.

Koskowski, M. R., 2019. Where's Wally? The role of heritage in cultural tourism: the case of travel selfies. In: C. Sousa, I. Vaz de Freitas, and J. Marques. eds. 2nd International conference on tourism research. Reading: Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited. 151.

Lee, W. and Chhabra, D., 2015. Heritage hotels and historic lodging: perspectives on experiential marketing and sustainable culture. Journal of Heritage Tourism 10(2), pp.103–110.

Mendiratta, A., 2013. Heritage hotels: Building a future by preserving the past. [Online]. Available from: < https://www.eturbonews.com/69384/heritage-hotels-building-future-preserving-past > [Accessed 1 March 2020]

Misra, M., 2008. Bam and its cultural landscape. The International journal of environmental studies 65(4), pp.603–619.

Moghadam, S. R., 2006. The Study on cognition and documentation of historic village of Saryazd. Translated from Farsi by Pegah Latifi. Tehran: Documentation Center and Library of ICTHO.

Munro, E., 2014. Doing emotion work in museums: Reconceptualising the role of community engagement practitioners. Museum and Society 12(1), pp.44–60.

Naiemi, A. H., 2018. Residential compounds: Earthen architecture in the central desert of Iran. In: S. Pradines, ed. Earthen architecture in Muslim cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp.203–232.

Pederson, A., 2002. Managing tourism at world heritage sites: A practical manual for world heritage site managers. [online] Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available from: < http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-113-2.pdf > [Accessed 16 March 2020].

Simeon, M. I. and Martone, A., 2014. Relationships between heritage, intangible capital and cultural and creative industries in Italy: A framework analysis for urban regeneration and territorial development. Advanced Engineering Forum 11, pp.149–156.

Solima, L. and Izzo, F., 2018. QR Codes in cultural heritage tourism: New communications technologies and future prospects in Naples and Warsaw. Journal of Heritage Tourism 13(2), pp.115–127.

Timothy, D. J., 2011. Cultural heritage and tourism: An introduction. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2017. Isfahan: Creative cities network. [online]. Available from: < https://en.unesco.org/creative-cities/isfahan > [Accessed 16 March 2020].

United Nations Information Centre (UNIC), 2014. UNESCO presents 2014 Asia-Pacific Award of Distinction for Cultural Heritage Conservation to Saryazd Citadel. [Online]. Available from: < http://unic-ir.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=978:une… > [Accessed 11 April 2019].

Urry, J. and Larsen, J., 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. London: SAGE.

Wilson, G. and McIntosh, A., 2010. Using photo-based interviews to reveal the significance of heritage buildings to cultural tourism experiences. Cultural tourism research methods 7, pp.141–155.

Sources for images

Fig 8. The second entranceway through to the lower floors of Saryazd Castle. Stanley, D. (2013). Main Corridor (8906626134), photograph, Accessed 18 August 2020, Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63935401. CC BY 2.0.

Fig 9. The iconic image of the Gate of Farafar. Bijan Moravej alahkami. (2019). Gate of Farafar, photograph, Accessed 18 August 2020, Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gate_of_Farafar.jpg. CC BY-SA 4.0

Fig 10. Birds-eye image of Saryazd Castle. مهدی خبره دست (2015), Saryazd Castle (Q5888459), photograph, Accessed 17 August 2020, Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:قلعه_سریزد.JPG. CC BY-SA 4.0